This weekend would have been the ninetieth birthday of Anthony Newley. I regret that he is not around to celebrate it as his great writing partner Leslie Bricusse has done. Newley was a prodigious talent, admired by our friend Don Black, who speaks movingly about him here, and by the late David Bowie.

Bricusse & Newley belonged to a London musical tradition that got more or less obliterated and forgotten in the unprecedented global phenomenon of Evita, Cats, Les Miz, Phantom and the other West End blockbusters of the Eighties. I myself have been prone to over look them, as my old confrère from the opening-night aisle seats, The Guardian's Michael Billington, has observed en passant:

In his excellent 1997 book, Broadway Babies Say Goodnight, Mark Steyn sniffily writes: 'British musicals? It still sounds like a contradiction in terms.' Steyn concedes the success of the Lloyd Webber canon including Cats, Evita and The Phantom of the Opera, but all of these transcend national barriers and are in no way peculiarly British. Indeed, what we seem to have witnessed in the last forty years is the emergence of the global musical that has as much resonance in Brisbane or Birmingham as it does in Berlin or on Broadway.

But is the British musical quite the glittering corpse Steyn suggests? One could point to a pre-Cats tradition that stretches from Gilbert and Sullivan to Lionel Bart.

I don't think I meant it quite as sniffily as Michael thinks - more as a characterization of what Broadway buffs make of "British musicals". G&S and Lionel Bart's Oliver! were transatlantic in their appeal, but far more common were massive London hits that had absolutely no resonance on Broadway - Chu Chin Chow, The Bing Boys, Vivian Ellis, Ivor Novello, Salad Days... Many of these shows produced exquisite songs (for example) but they were a little too English in their sensibility to travel, at least to New York.

So, in honor of what would have been Anthony Newley's ninetieth birthday, here's a bizarre exception to that tradition: a British musical that flopped in Britain, bypassed London entirely and went straight to New York. It's also an exception to a more recent tradition: it was a 1960s show score that produced multiple stand-alone take-home pop tunes at a time when rock'n'roll was crowding Broadway off the Hit Parade.

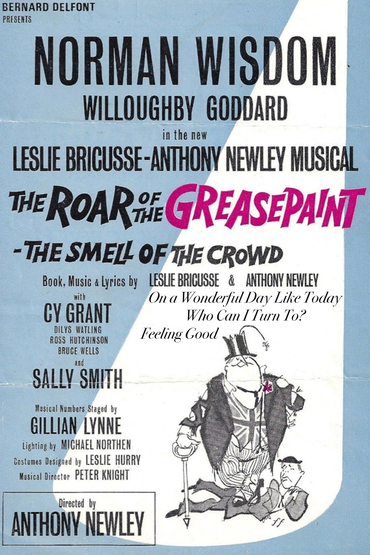

The original production opened on August 3rd 1964 at the Theatre Royal, Nottingham in the English Midlands. The Roar Of The Greasepaint, The Smell Of The Crowd was a British musical from that pre-Lloyd Webber era Michael Billington referenced – that's to say, the days when, with a handful of exceptions, they were considered strictly for local consumption. In the case of Roar Of The Greasepaint, even the locals declined to consume: It sputtered in Nottingham, died on tour, and never made it to the West End. And yet a floppo Brit musical by Leslie Bricusse and Anthony Newley managed to produce a trio of enduring songs:

The first was a classic showbiz rouser:

On A Wonderful Day Like Today

I defy any cloud to appear in the sky

Dare any raindrop to plop in my eye

On A Wonderful Day Like Today!

That's one of those songs no one would write if there weren't stage musicals to write them for. It's what Hal Prince calls "a once-a-year-day number", after the song of the same name in Pajama Game: a moment of such infectious peppiness that is its own justification. It was everywhere in the mid-Sixties and Seventies, a surefire opener for TV variety shows. A few years ago, when Andy Williams put together a best-of-the-guests compilation from the archives of his weekly show (Bing, Ella, Bobby Darin, Sammy Davis), he shrewdly chose a performance of "Wonderful Day Like Today" as his opener – the definitive opener, one that sums up an entire television genre.

The second song from Roar Of The Greasepaint was the big ballad:

Who Can I Turn To

When nobody needs me?

My heart wants to know

And so I must go

Where destiny leads me...

Tony Bennett picked it up and made it a Top Three pop hit, so today it turns up on all those Tony Bennett Duets with [Insert Name Here] albums. But over the decades all kinds of other people took a yen to it. Van Morrison wouldn't seem to have much in common with Anthony Newley, but he made a terrific record of it a few years back:

The third song was the slow-burner, the one that didn't seem a big deal at the time, but looks set to be the most enduring of all:

Birds flying high

You know how I feel

Sun in the sky

You know how I feel

Breeze drifting by

You know how I feel

It's a new dawn

It's a new day

It's a new life

For me

And I'm Feeling Good...

"Feeling Good" wasn't sung on stage by one of the two leads but by a character called "the Negro". Nina Simone came across the number and made one of those records that was never a big Top Ten hit but wound up lasting longer than ninety per cent of the ones that were:

And, as the years went by, fellows who were barely aware of Tony Newley or Leslie Bricusse started making, in effect, cover versions of the Nina Simone record, just because it was so damn cool. Traffic did it, and the Pussycat Dolls and George Michael, and the version by Muse won the "Best Cover Version of All Time" poll in New Musical Express.

If we were willing to play fast and loose with definitions here at Song of the Week, we'd throw in a trio of other Roar Of The Greasepaint songs that bust out of their stage context: "Where Would You Be Without Me?" became one of those numbers that turn up on TV when the host needs something to do as a duet with the star guest; "The Joker" was recorded by Bobby Rydell and Sergio Mendes; and "Look at That Face" was taken up by Barbra Streisand, Mel Tormé, Carmen McRae and every other discriminating balladeer. But, compared to that first trio, they remain something of a specialized taste. Even so, that's impressive: Three big songs, three more modest breakout tunes, and all from a British show no Britons wanted to see.

What was The Roar Of The Greasepaint, The Smell Of The Crowd that it could produce such a score? Well, it was intended to be a follow-up to Bricusse & Newley's hugely successful first musical, Stop The World – I Want To Get Off. Like Stop The World, its successor had a clever title - an inversion of the stage performer's summation of the theatrical life: The smell of the greasepaint, the roar of the crowd. The sensory pleasures of performance were known mainly to one half of the Bricusse/Newley partnership: Bricusse is a writer of music and lyrics brought to life by others; Newley was a writer ...and an actor and a singer; a performer all his life since landing the title role in the British children's serial The Adventures of Dusty Bates. A poor boy born to an unmarried mum in the East End, young Tony Newley came to the attention of David Lean, who cast him as the Artful Dodger in his film of Oliver Twist. "Every day," he told me, "I'd cycle from Clapton to King's Cross, take the train to Pinewood, then the bus to the studio to be directed by David Lean in scenes with Alec Guinness. Then, every night I'd return to that street and live in one room with my mother. Why wouldn't one want to stay in that world? Why would one want to go back to Clapton?"

He didn't. He went on - to New York, and Hollywood, and Vegas, where he was the "Male Musical Star of the Year" in 1977. There are any number of partnerships where one half is an on-stage star and the other half isn't - Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, Burt Bacharach and Hal David, Elton John and Bernie Taupin... And you assume it's the guy who isn't getting the ovations and groupies who must be the resentful, festering, embittered soul. But when I first met Bricusse & Newley years ago it was the off-stage half - Leslie Bricusse - who radiated the permatanned contentment of the glamorous life (he lived round the corner from Ira Gershwin) - and the Vegas star - Newley - who was all tormented and eaten up.

He'd had a strange career. Before Stop the World, Newley was a rock'n'roller, spoofing Elvis in the film Idle on Parade (1959). But the parody was mistaken for the real thing, and the songs made the charts. In later life, he wrote and sang for real, while always teetering on the brink of self-parody and often diving straight in. All those mannerisms – the splayed feet, the cupped hands, the exaggerated furrows of the brow, the strange vowel sounds -, surely he couldn't mean it? "I wasn't aware of my effect," he told me. "I was so inside the lyric, my body had a life of its own. When I first saw myself imitated, I was in shock for days. They made me look and sound like a freak: 'Gonna build a mown-tine.' I swore I'd never take my hands out of my pockets again. I may sing like Marcel Marceau, but it was never a style. It's just the way I make my noise."

I always liked that phrase of his: "I was so inside the lyric." Newley was always "so inside" what he was doing. Eventually, he got "so inside", he disappeared. But in the early Sixties Stop the World and Roar of the Greasepaint were protean "concept musicals". The term wasn't really in currency then, so they were dignified as "allegories", concerned less with plot than with the Big Meaning, and for a while Bricusse & Newley were hailed as "new wave" mold-breakers. Even at the time Leslie Bricusse was more relaxed about the whole business. "We wrote these terrible parables of life," he said to me a few years ago. "Stop the World is the Seven Ages of Man in modern terms. Roar of the Greasepaint, Smell of the Crowd is about two survivors after The Bomb. The Good Old Bad Old Days is God, Man and the Devil. They were really just entertainment vehicles for Newley, but he had these intellectual pretensions that I'd try to hold down. He always wanted to declaim from the mountain, and eventually he succeeded. He made a film called Can Hieronymus Merkin Ever Forget Mercy Humpe and Find True Happiness? where he stood on a mountaintop dressed like Jesus and sang 'I'm All I Need'. It was nice, but I think I would have stopped him doing that."

Roar of the Greasepaint's two post-nuclear survivors are archetypes - the patrician "Sir" and the lowborn "Cocky", because even the H bomb can't kill the British class system. Six decades ago at the Theatre Royal, Nottingham, Sir was played by Willoughby Goddard, to whom it fell to introduce "On A Wonderful Day Like Today":

On a morning like this

I could kiss

Ev'rybody

I'm so full of love and good will

Let me say furthermore

I'd adore ev'rybody

To come and dine

The pleasure's mine

And I will pay the bill...

In context, it seems tailor-made for Willoughby Goddard's rotund bonhomie, yet Lena Horne made a groovy little record of it:

In my teenage years, I inveigled my way into a village entertainment because there was a bird in the cast I wanted to put the moves on, and it seemed the easiest way of getting to see her night after night. The am-dram directrix handed me "Wonderful Day", and, being into a lot of terrible progressive rock at the time, I was aghast at the prospect of having to sing in public what I regarded as a supersized slab of cheesy hokum. The last time I mentioned this a longtime SteynOnline reader Daniel Hollombe, a boomer-pop aficionado, reckoned this confession explained everything:

So that's your problem. You went straight from Emerson, Floyd & Wakeman, and delved straight into Anthony Newley, completely bypassing anything and everything in between. You'll just have to take my word for it when I tell you that you're missing out on a lot of great musical craftsmanship that is easily as melodic as "On A Wonderful Day Like Today," that simply wasn't composed for any stage show or movie.

Maybe he's right. Maybe I should have transitioned less alarmingly, from Genesis and Camel to the Tremeloes or Duran Duran. As for "Wonderful Day", once I was up on stage I sorta found it irresistible – in part because you have to be a total incompetent not to stop the show with it:

May I take this occasion to say

That the whole human race should go down on its knees

Show that we're grateful for mornings like these

For the world's in a wonderful way!

On A Wonderful Day Like Today!!!

In Nottingham, the common little everyman Cocky was played by Norman Wisdom. A very British star who never quite made it in America, Wisdom usually played an idiot not-so-savant with plenty of room for slapstick. Beyond the Commonwealth, he was a huge hit in Communist Albania, where the idiosyncratic dictator Enver Hoxha allowed no other western films but Wisdom's to be shown to his people. But Norman Wisdom had a musical side, too. His signature song was a lachrymose ballad called "Don't Laugh At Me 'Cause I'm A Fool". "Who Can I Turn To?" is obviously a kind of sequel to Stop The World's interrogatory ballad, "What Kind of Fool Am I?", but clearly Bricusse & Newley tailored it to Wisdom, too:

Who Can I Turn To

When nobody needs me?

My heart wants to know

And so I must go

Where destiny leads me

With no star to guide me

And no one beside me

I'll go on my way

And after the day

The darkness will hide me...

And no, as you can tell from the orchestration, that's not the original cast album: The English production was such a flop that plans to record the show were scrapped. But Norman Wisdom liked the song enough to have Highland lassie Moira Anderson sing it at his funeral. It's easy to see Norman wallowing in the lugubrious self-pity of the thing, and kind of impressive that Tony Bennett heard something else in it. Certainly few singers have ever been shorter of people to turn to than Bennett: Since his original take, he's recorded it with Queen Latifah and a couple of years later with Gloria Estefan and who knows who else. (A few years back, I was in a Starbucks with my daughter and she picked up that week's Bennett all-star duets CD at the counter and mused offhandedly, "Tony Bennett's really the duet slut, isn't he?")

For all his music, libretti, screenplays and children's books, Bricusse seems to take most delight in in the intricate word puzzles which lyric writing involves. "I share with Alan Jay Lerner the feeling," he said to me, "that the lyricist is the guardian of the purity of the language." Maybe, but Lerner, lyricist of Gigi and Camelot, once told me he thought Bricusse's "Who Can I Turn To?" would be improved as "Whom Can I Turn To?" and, passing the thought on to Bricusse, I said personally I'd settle for nothing less than "To Whom Can I Turn?" But the author doesn't take this sort of thing lying down. Lerner, in the opening number of My Fair Lady, commits the great solecism of having Professor Henry Higgins, a supposed master of the English language, sing:

By rights they should be taken out and hung

For the cold-blooded murder of the English tongue...

Leslie Bricusse sent Lerner a note:

By rights you should be taken out and hanged

For the cold-blooded murder of the English tanged...

On reflection, I think Lerner and I were wrong. "Whom Can I Turn To?" , never mind "To Whom Can I Turn?", would just get in the way. If you listen to Van Morrison's recording from 2006, it's a great bluesy wail, and the prepositional end is not merely something up with which we should put but is necessary for the vernacular authenticity of it.

There were three other characters in Roar of the Greasepaint - "the Kid", "the Girl", and "the Negro". The last was played by Cy Grant, born in British Guiana and the first black man to appear regularly on UK television: on the BBC news show "Tonight" he'd had a regular gig for a couple of years singing a "topical calypso" strung around stories from the day's headlines. If a British musical goes to the trouble of making one of its five characters "the Negro", it's no surprise they'd want him to have a solid song. Bricusse & Newley wrote him something in the spirit of the times without ever getting explicit about them:

Fish in the sea

You know how I feel

River running free

You know how I feel

Blossom on a tree

You know how I feel

It's a new dawn

It's a new day

It's a new life

For me

And I'm Feeling Good...

After the original English tour, Cy Grant made a jazzy little record of it with the pianist Bill Le Sage - and rather overdoing the echo chamber in the intro:

After that, John Coltrane and Chris Connor and Sammy Davis got into it. Nina Simone moved it into r'n'b territory, and then the rock guys wanted a piece of it. Because Bricusse & Newley's greatest song was written to another man's tune - "Goldfinger" (music by John Barry) - I always thought of them as lyric writers who happened to compose music because nobody else was at hand: If you look at "Wonderful Day" or even "Who Can I Turn To?", they're what Sammy Cahn once described to me as "the kind of tune a lyric writer writes" - with internal rhymes to remind themselves of where they need to put the melody's stresses. But "Feeling Good" has a musical sensibility on an entirely different level.

Nobody spotted it on that English tour, alas, as Leslie Bricusse ruefully acknowledged to me many years later. "We took the biggest star in the country – Norman Wisdom – and managed to empty every theatre in the land. I went to see Norman in Liverpool in Sinbad in a 2,800-seater jammed to the roof. Six months later we were in the same place, and there were five people at the Saturday matinee."

"So," I asked, "with the wisdom of hindsight, do you think...?"

"The wisdom of hindsight?" he interrupted me with a hollow laugh. "The Norman Wisdom of hindsight can be very illusory," he cautioned.

It all worked out. David Merrick, Broadway's "abominable showman", caught Greasepaint on tour, and figured he could make money on it in America with Anthony Newley in the lead. In the end, it came to Broadway for eight months in 1965-66, but by then Merrick had recouped his investment on the US road tour, and that was enough. Everything about the show was a hit - except the show. Hit songs, hit star, hit writers ...but no hit musical.

Arthur P Jacobs, producer of Planet Of The Apes, was looking for a songwriter for Dr Doolittle and heard some numbers Bricusse had written for an unproduced musical about Noah. "I was sold to 20th Century Fox on the basis that here was a guy who wrote animal songs. They said, 'Great, great – we'll make a demo.' So we go to Fox and make a demo – me singing 'Talk to the Animals' with a 75-piece orchestra. For a demo? Well, that's Hollywood." Bricusse won an Oscar, and so a permanent team became an occasional one. They got together to write the film of Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory and got a Number One record out of it with "The Candy Man" - and that was it for Bricusse & Newley.

"Why did we stop? Neither of us knows the answer," Newley said to me many years ago. He had a Bob Dole-esque habit of talking about himself in the third person. (When I asked him about his version of "What Kind Of Fool Am I?", he said, "Newley sings it in a way that personalizes it.") So, on the break-up with Bricusse, he put it this way: "Newley and Bricusse would both like to find another Newley and Bricusse, with somebody else – just to change the sheets. You have mixed emotions about any collaboration – there's a lot of subjugation, a lot of domination." He stopped, creased his brows and stared with closed eyelids into the distance, as if wrestling with some new concept. "Being gifted without discipline is a wasted gift. I lack discipline. Leslie brought form to my passion. In print this won't look too good over breakfast, but I have to say there is more to this chapter of our being then we know. I have probably been in a family relationship with Leslie in twelve previous lives."

He wasn't exactly feeling good, but he was feeling reasonably confident that in some future life or twelve he and Bricusse would be writing more musicals together. "Leslie has always been disappointed in me because I didn't continue. We wrote these extraordinary shows, and then I just put on a dinner-jacket, started singing and gave them up."

Anthony Newley died twenty-two years ago. By contrast, Leslie Bricusse just kept going - Victor/Victoria with Henry Mancini, Jekyll & Hyde with Frank Wildhorn (who wrote Whitney Houston's "Where Do Broken Hearts Go?"), a biotuner about his pal Sammy Davis Jr... He was kind enough to ask me along when he was inducted into the Songwriters' Hall of Fame in the Nineties: Cocktails at Liza Minnelli's beforehand, Jackie Collins, Quincy Jones, Dick Clark, Patti LaBelle... He always has a half-dozen projects on the go, too busy living this life to the full to worry about his twelve previous lives. He insisted he's "never thought of songs as having national characteristics", but he was proud of being only the fourth Englishman in the Hall of Fame, after Noël Coward and Lennon & McCartney. As for "my beloved Newley", "we're still mates but we stopped writing together years ago. And, without looking a gift horse in the mouth, I cringe every time I hear 'What Kind of Fool Am I?' or 'Who Can I Turn To?' I can't bear them anymore. There is life after Newley."

True. But, six decades on, one strange, unique Bricusse & Newley song is the slender thread that connects Michael Bublé, Frank Sinatra Jr, George Michael, Jennifer Hudson, Kanye West, David Hasselhoff and a zillion others to Norman Wisdom and a BBC calypso singer on a disastrous tour of the English Midlands in the summer of 1964:

Stars when you shine

You know how I feel

Scent of the pine

You know how I feel

Freedom is mine

And I know how I feel

It's a new dawn

It's a new day

It's a new life

For me

And I'm Feeling Good!

On this Newley ninetieth, let's close with him in the show's little-man persona and what was always a big showstopper for him, if not for Norman Wisdom:

~If you'd like to hear Mark sing Bricusse & Newley, here's the Bond song they wrote with John Barry, which became the title song of a Steyn CD - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter your promo code at checkout for special member pricing.

If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we now have an audio companion, every Sunday on Serenade Radio in the UK. You can listen to the show from anywhere on the planet by clicking the button in the top right corner here. It airs thrice a week:

5.30pm London Sunday (12.30pm New York)

5.30am London Monday (2.30pm Sydney)

9pm London Thursday (1pm Vancouver)

If you're a Steyn Clubber and you're not feeling good about the above column, feel free to weigh in in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page.