The whining roar of jet engines is the first thing you hear – too loud and too close – and then the camera quickly pans across the canyon walls of downtown office towers to catch the plane as it disappears into the sunlit side of the massive building, the fireball and debris exploding out a fraction of a second later.

When American Airlines Flight 11 flew into the North Tower of the World Trade Center, there were just three cameras that caught the horrible moment. One was a web cam set up by an artist, Wolfgang Staehle, to document the mundane daily view of the Manhattan skyline from Brooklyn – a Warholesque project that became much less mundane in a few seconds. Another was a shaky shot taken by a Czech tourist, Pavel Hlava, from the passenger seat of a car as he was driving into the Brooklyn entrance of the Hugh L. Carey Tunnel into Manhattan.

The third, and most vivid, was taken by Jules Naudet, a French-born documentary filmmaker working with his brother Gédéon on a film about a rookie firefighter at a station in Lower Manhattan. Jules' brother was the cameraman of the team, but Gédéon had sent his younger brother out on the morning of September 11th with Fire Chief Joseph Pfeifer and other crewmen to investigate the report of a gas leak just a few blocks north of the World Trade Center, and get some experience using their Sony DV cam.

Jules was shooting unremarkable footage of Pfeifer and his crew working with their gas meters on the street when the sound of jet engines makes them look up, and the inexperienced cameraman captured the impact and its aftermath – following Pfeifer into the North Tower where the chief helped set up a command post to rescue survivors and fight the fire blazing 90 storeys above them.

It's hard sometimes to remember that a whole generation has been born since 9/11 – even when that includes my own children. Along with the fall of the Berlin Wall just over a decade earlier, it's one of the only times in my life when I knew I was witnessing history happening, and like most people who watched it that day, I can recall nearly everything that happened from the moment I got a call from a friend early that morning telling me to turn on the TV.

The weeks and months that followed are more of a blur, but what I do remember is leaving the TV on almost all the time, tuned to cable news channels, hoping that somewhere in the constantly recycling coverage there'd be something new to learn – something to explain just what had happened, and why. The best depiction of this bleary, stunned time is an episode of South Park, where Stan's mom lies zombie-like on the living room couch, transfixed by the television and its grinding retelling of every event since that morning, with incremental, agonizing updates.

I collected everything I could that might explain what happened – printouts of stories from newspaper and magazine websites, books and, eventually, DVDs. This was how I ended up with 9/11, the documentary the Naudets ended up making with their footage, released by Paramount a year later.

When Jules Naudet follows Chief Pfeifer into the North Tower, it's a scene of devastation even hundreds of feet below the fire. Lobby windows are shattered and huge squares of marble have fallen from the walls. Naudet discretely turns his camera to the left as he walks through the revolving doors; to his right, two people are on fire from the jet fuel that exploded down the elevator shafts.

It's obvious that this is something none of the first responders – the police, security personnel, paramedics and especially the firefighters – have ever seen before. Regardless, training and instinct take over and the firefighters shoulder their gear and begin heading up the stairs to the impact site. In a voiceover James Hanlon, a NYC firefighter who the Naudets had been working with on their documentary, tells us that it takes about a minute for a fully-loaded crewman to walk up a single storey, and that it will take over an hour for the men we see in the lobby to make it to the fire.

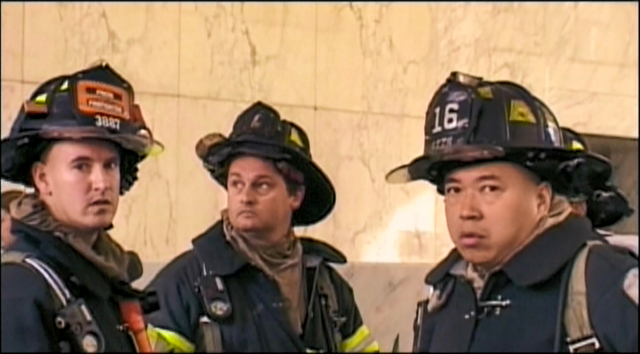

One of the men sent up the stairs by Chief Pfeifer is his younger brother, Kevin. He will never see him again. As Jules Naudet's camera pans over the faces of the firefighters in the lobby of the North Tower, you realize with shock that his footage, which includes Kevin Pfeifer, is the last time many of them will be captured for posterity.

Back at the fire station Gédéon Naudet has been left behind with Tony, the probie who had been the focus of their project. Knowing that his brother is with Chief Pfeifer on the scene, he realizes that he'd innocently sent him into danger, and the guilt forces him outside to record the crowds on the street, staring amazed at the smoke billowing out of the North Tower.

He's just at the right spot to be one of the cameramen – by now many more than there were just over fifteen minutes earlier, when Flight 11 hit the North Tower – who capture United Airlines Flight 175 smashing into the South Tower just above the 77th floor.

In the lobby of the North Tower, Jules Gédéon's camera records the explosion from the impact of Flight 175, and captures the rain of debris falling into the square outside the building. This is not the most horrifying thing that Jules' Sony camera will document that day.

All during his time in the lobby following around Chief Pfiefer, there are horrible, loud explosions outside, at increasingly shorter intervals. It's the sound of people, jumping from the blazing floors above the impact zone, deciding between a slow death in flames and smoke and one just as certain, albeit quicker, when they hit the awnings and pavement at the base of the towers.

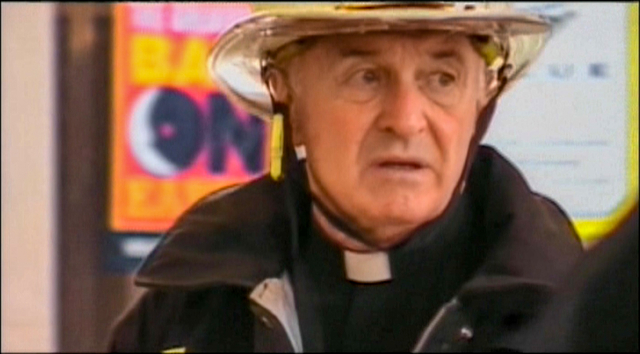

Jules' camera holds on Father Mychal Judge, the chaplain of the New York City Fire Department, as he paces alone around the lobby of the North Tower. He imagines that Fr. Judge is praying, but it's hard not to notice the worry on the chaplain's face, and even a trace of fear – the same growing fear that he is seeing on the faces of the firefighters when they realize, after the second plane hit, that they weren't at the scene of an accident.

By this point anyone watching 9/11 will understand that much of what we're watching – Fr. Judge, the firefighters and other first responders passing through the lobby of the North Tower on their way to the stairwells, and even the lobby itself and the buildings outside – will very shortly be gone, and that this is the last time anyone will see this place, these people.

Outside on the street Gédéon Naudet is filming as he makes his way down from the station to the Towers, his camera panning up to the two towers, trailing long banners of smoke and debris out into the clear morning sky, to the people on the streets below, some crying, some asking others with obvious shock if they know what they're watching.

One thing that it's hard for me to ignore is the absence of smart phones, held up with one hand, capturing slim vertical footage of the unfolding disaster. Occasionally Naudet glimpses someone with a "real" camera – by now stringers and freelancers and photographers from the newspapers have begun to throng the scene. And we do see onlookers with cellphones – flip phones mostly. There are lineups at the payphones, as cell service overloads and fails with every minute since the planes hit.

But no one is pointing their phones skyward; everyone we see is witnessing the attack unmediated, without a thought of capturing it for social media that doesn't exist yet. If the attacks happened today we would have an embarrassment of footage, pretty much from the second the first plane hit the towers, captured in the background of selfies taken in the plaza below, from the observation deck on the South Tower or the Windows on the World restaurant in the North Tower, or on streets in every direction from the WTC, and across the water in Brooklyn, Staten Island and New Jersey.

Once captured and uploaded, it would be the last record of what victims of the attacks saw before their death. Twenty years ago that baleful possibility was not an option, and I think many people will be grateful that it wasn't.

Watching 9/11 for the first time in many, many years I'm forced to realize that, while the events of that day are still vivid in my memory they are – utterly and irretrievably – history. The lack of smartphone captures, and the lo-fi quality of the footage from the Naudet's Sony DV cams – excellent quality at the time, just a few steps below larger, more expensive video cameras, but now nowhere near the resolution of an iPhone – pins this record of the day in time, like the blurry analog footage from previous generations of video cameras, the shaky frames of Super 8, grainy newsreel footage shot on 16mm stock between the '40s and the '60s, and the short bursts of skittering hand-cranked film from the early, silent era.

Watching news footage shot on the scene by cameramen like Gédéon Naudet, we saw things we thought we'd seen before – like the crowds running through the streets, chased by a wall of white smoke and powder roaring out from the collapse of first the South, then the North Tower. It was a staple of disaster movies like Independence Day, released just five summers earlier. (Just a few minutes before the South Tower falls, Gédéon Naudet films a man hugging the scaffolding around the street level of a building, looking up and marveling that it looks "just like The Towering Inferno.")

In the North Tower, Jules Naudet is caught in the cloud of debris that bursts into the lobby when the South Tower falls. Using the light on his camera to help firefighters navigate the now-transformed space, they find the body of Fr. Judge, lying at the bottom of the escalator, just a few yards from where Jules had filmed him, still alive.

The possibility that the towers could fall was apparently on the minds of almost no one except the hijackers. I remember watching the TV that morning, still in shock after the second tower was hit and hearing that yet another plane had hit the Pentagon ("It's war now" I said to my wife – not a terribly original thought, but an accurate one.) My tiny modicum of knowledge as an architecture geek made me wonder if a collapse was possible; I banished the thought, at least until the South Tower began to tumble.

"It just came down," says one of the firefighters interviewed by the Naudets. "It wasn't supposed to come down."

In the North Tower, firefighter radios are suddenly filled with mayday calls, and in the stairwells the crews that had climbed halfway or more up the building turn and retreat back to the street. Exiting the WTC complex with Chief Pfeifer just behind the North Tower, Naudet still has no idea that the South Tower is completely gone.

Outside, Gédéon Naudet is trying to get as close as he can to the Towers, and he films the scenes we now associate indelibly with 9/11. More often than not they're surreal, like the shot of two firefighters with their gear walking into the smoke, toward the Towers, passing an overweight businessman in spectacles and shirtsleeves, till clutching his briefcase, walking catatonically away from the disaster.

Gédéon is sure that his brother is dead. When the North Tower falls, both brothers are sure they're going to die. At one point they're less than a block from each other in the cloud of smoke and debris. Back at the firehouse Gédéon counts the crew as they straggle back, his panic rising with each minute Jules doesn't appear. The younger Naudet finally returns, arriving so quietly that his brother doesn't notice him until he's at the back of the empty garage. There's an emotional reunion, amplified when Tony, the probie, returns from the WTC site as the sun sets, covered in dust, after following a retired Chief down to the Towers that morning to make themselves useful.

Unbelievably, every member of the crew of Engine 7/Ladder 1/Battalion 1 survived the collapse of the Towers – a miracle since they were one of the firehouses closest to the WTC. But they all line up to sign on to roster sheets volunteering to join rescue efforts at the Towers, and even when given an order to hold at the firehouse until further orders, some of them hitch a ride on another engine (their own have been crushed by the Towers) and head downtown.

This is where 9/11 showed us something we'd never seen before – the devastation at what we'd call Ground Zero. There had been cities in ruins before – earthquakes had shattered many cities, both World Wars had devastated towns with increasing efficiency. Within living memory of the attacks there had been Beirut – one of the apparently unsolvable catastrophes of the Middle East which would be packaged together as cause of the blowback that culminated in 9/11, in many of the post-mortems, rich with knowing hindsight, we'd read in the months and years that followed.

But the ruins of the Towers – Ground Zero – were unique. It had happened in an American city – the American city, as far as most of the world was concerned – and it involved two of the greatest structures that city or any other could imagine building. They'd fallen into the deep pit of their own basements and into the transit tunnels below them, and they'd fallen into their own plaza and the streets around them, taking down adjacent buildings, changing the skyline of New York City.

The shots Jules and Gédéon Naudet take of Ground Zero – shrouded in the lingering cloud, shards of the metal skin of the Towers spiking the mountain of debris – were among the first visions the rest of the world had of the disaster. It was actually a lot smaller than many people expected it to be, but that was because the Towers were, thanks to their cutting edge design, mostly air. (That design would also be the reason why they would inevitably fall.)

Somewhere in there were the victims, nearly 3,000 of them, and thanks to the pulverizing descent of the towers, many would never be found, and most would never leave behind more than a fraction of themselves. One firefighter interviewed by the Naudets marvels that, on a site that had contained hundreds of offices and thousands of desks, he never saw anything bigger than half of a telephone keypad.

It only took eight months to clean up Ground Zero, but rebuilding would take years, with One World Trade Center, 104 floors tall, breaking ground in the spring of 2006. The Sony DV cam Jules Naudet used to film 9/11 is on display at the National Museum of American History. The nineteen hijackers who caused so much devastation were beyond the reach of vengeance, and by the time U.S. special forces killed the apparent mastermind of 9/11 in 2011, Osama bin Laden was yesterday's man, a ghost in hiding as his terrorist army sprouted all over the world, under many different names.

Right now the wars started to avenge the attacks seem like pointless adventures or so much waste of lives and treasure, squandered by feckless politicians and planners and intelligence agencies with little apparent skill at either. It would have been hard to believe that we'd be in this place twenty years ago, but that's just one more thing that makes 9/11 history.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.