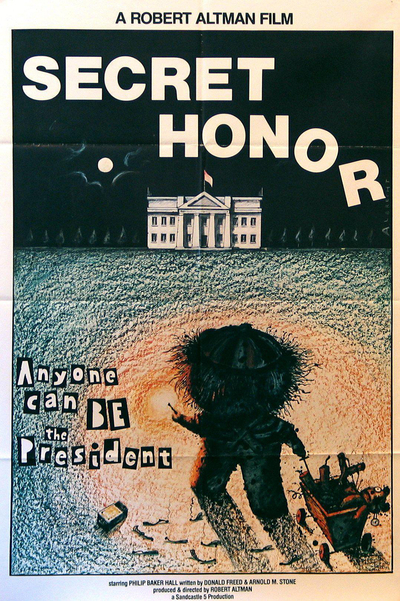

Robert Altman was in exile when he made Secret Honor, shooting in a women's residence at the University of Michigan's Ann Arbor campus, using a crew of mostly students. To be fair, it was a cushy sort of exile, as Altman – merely a visiting lecturer – had been given an office befitting a prestigious tenured professor by the university's film department, which he used as a base to continue his campaign to return to Hollywood. In 1984 that meant a movie about another man in exile – disgraced former US president Richard Nixon, alone and drunk in his New Jersey study.

Altman was in exile from Hollywood because of Popeye, the 1980 musical comedy starring Robin Williams and Shelley Duvall that had been a very strange choice of project for the man who'd made M*A*S*H, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Long Goodbye and Nashville. Altman was a maverick, however, and though the film made more than its budget back, it had been deemed a flop by Paramount and Disney, mostly because of underwhelming reviews, and Altman was persona non grata.

Credit: Rick McGinnis |

The '80s were a difficult time for Robert Altman after his glorious '70s, and he bided his time with a grab bag of projects including O.C. and Stiggs, a film based on a series of National Lampoon stories. He spent most of the decade adapting plays like Streamers, Fool for Love, Beyond Therapy and Come Back to the Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean to the screen. Secret Honor was another one of these – a one-man show that he knew he wanted to film as soon as he'd seen it at a showcase run in Los Angeles.

The film begins with Nixon, played on stage and on film by the then-unknown character actor Philip Baker Hall, changing into a red velvet smoking jacket and settling in for the night in his study. He comically fiddles with his new tape recorder as he prepares to dictate notes that will be transcribed by an aide, Roberto, about whom we know nothing except that he's Cuban-American. (Haldeman and Ehrlichman are long gone.) The other two significant props are a bottle of Chivas Regal and a revolver.

Hall had spent most of his career either on the New York stage, or doing guest spots on TV shows, including the TV version of M*A*S*H. While working on the film with Altman – the two would lie on twin beds in an adjacent room and talk about the next scene, sometimes holding hands – the director would ask Hall why on earth he'd never heard of him before.

Nixon's study is a luxurious wood-paneled space befitting a retired statesman, with two notable features. One is the bank of CCTV screens, one camera trained on his desk. The other are the half dozen oil portraits hanging around the room: Washington and Lincoln facing each other over the fireplace and piano ("You were my mother's piano and that f--king museum is not going to get you!"), Woodrow Wilson and Eisenhower by Nixon's desk, and Kissinger and LBJ in the corner by the CCTV screens.

After a halting list of instructions, he starts dictating what seems to be an autobiography in the form of a lawyer's defense of his client, where Nixon plays both attorney and accused. He begins with Gerald Ford's pardon, which he says wasn't a pardon at all, since he was never charged or found guilty, and in any case it wasn't much of a pardon since he remains guilty in the eyes of both his accusers and the public.

"I'll forgive them before they ever forgive me!" Hall-as-Nixon barks.

Hall's Nixon is profane and digressive, haunted by decades-old slights and taunts, full of anger and resentment, the wrathful paranoid revealed in the White House tapes now fully unrepressed by either his fall from great office or the whiskey. His mood swings from maudlin to enraged, often in seconds, and he clearly sees himself as a tragic figure. "I could always cry in public," he brags, recalling that his high school dramatics teacher praised him as "the most melancholic Dane he had ever directed" and that despite what the media used to say about Adlai Stevenson "it was me who was Hamlet" and that Ike was the King.

The turning point in his life, he says, was when he answered an ad looking for war veterans to run for congress, placed by a group of California Republican businessmen he calls the "Committee of 100." They would fund his first campaign in 1946, which he would win, but Hall-as-Nixon makes them a persistent force in his life, a group of "winners" as the former president describes them, rich men who had a plan for the young lawyer from humble beginnings.

They took him to Bohemian Grove, the onetime artists retreat among the northern California redwoods that's evoked in countless plutocratic conspiracy theories, alongside Davos, the Bilderberg Group, the Trilateral Commission and the Council on Foreign Relations. "That's where I got the message," Nixon says, among the barking dogs and guards, the rich men singing football songs and the prostitutes brought in from a nearby town.

"I may have said some things there that would come back to haunt me."

It's worth noting here that one of the authors of Secret Honor was Donald Freed, a writer with a very interesting CV. He began his career as an investigative journalist in the '60s, and was the author of books on the killings of Robert Kennedy and the Chilean politician Orlando Letelier, an investigation into O.J. Simpson's murder of his wife Nicole, and the trial of Black Panther Bobby Seale.

He was a member of the Friends of the Panthers, who ended up on Nixon's enemies list, and would be hired by Jim Jones' People's Temple to write a defense of the cult alleging a conspiracy by intelligence agencies against Jones and his group, visiting their community in Jonestown just before the mass suicide in 1978.

Freed was also co-author of the novel and screenplay for Executive Action, the 1973 Burt Lancaster film describing a plot to kill John F. Kennedy, spearheaded by a cabal of industrial, political and intelligence groups. His collaborators on the story were conspiracy theorist Mark Lane and blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, and the film joined The Parallax View, Seven Days in May, Three Days of the Condor, Winter Kills, The Manchurian Candidate, Wag the Dog and JFK in the pantheon of conspiracy theory cinema.

There are many moments in Secret Honor that will be familiar to avid Nixon obsessives: his constant instructions to Roberto to erase the tapes at some point previous to an emotional digression, his envious hatred for the Kennedys (though he retains a soft spot for Jackie, who was nice to him; Nixon-as-unpopular-kid-in-school) and his bitter resentment of Kissinger, the latter burning much more hotly than the former.

"Henry Asshole Kissinger!" Hall-as-Nixon snarls at the smirking portrait hanging over the CCTV screens. "Doctor Shitass!"

"I made you and I can break you," Hall's Nixon threatens the painting. "They gave you the Nobel Peace Prize and me they called the Mad Bomber!" he complains bitterly, insisting that the Cambodia bombings were always Kissinger's idea.

"They gave that whoremaster the Nobel Prize!" Nixon exclaims with disbelief. (It's worth remembering that our perception of the award as a laurel for people who actually reduced the amount of bloodshed in the world has been dismantling itself for many decades, and not just since it was given to Barack Obama as a participation prize.)

The so-called "paranoid style" in US politics – at least its modern iteration – is supposed to have begun with the JFK assassination, but it was amplified by Nixon and Watergate, if you believe the people who like how the paranoid style helps them paint a frame around their political enemies. Secret Honor is fully in the paranoid key, with Hall's Nixon bemoaning that "Uncle Sam – he's become nothing but a pitiful giant, an old man being eaten alive by the Bilderbergers and Ralph Naders and Jane Fondas..."

"You know what, Roberto – you are blind" he suddenly announces, addressing his unseen aide. "You watch out, seňor, because your turn is coming, all you new guys, you Cubans, you immigrants, you'd better watch out for the liberals – hmm, hmm, yeah – the colored found that out but it was too late. It was the North, not the South! Oh yeah, they'll come after you just the way they came after me!"

(Nixon, however, was proof of the tired old maxim about paranoia that sometimes they really are out to get you.)

With Watergate nearly half a century in the rear view mirror, it would seem that the Hunter S. Thompson/Ralph Steadman caricature of Nixon has triumphed. Hall's performance as Nixon owes a lot to their awkward loner/drunken madman/American Id vision of the 37th president, but there are startling moments where Hall/Altman/Freed humanize the man in the midst of his breakdown.

He becomes submissive, even abject, whenever he talks about his mother; in one of the most poignant moments in the film, he rediscovers an old letter he wrote to her, hidden in her Bible. He describes his ill treatment while she's away, imagining himself not as a boy but as "your good dog, Richard." Later he's on his knees, gently imploring the recurring vision he has of her.

"Arf," he barks, softly, bathetically. "Arf."

Recalling the 1950 senatorial campaign, where his use of "dirty tricks" were refined, his torrent of raging memoir is stopped short when he says the name of his opponent, Helen Gahagan Douglas. "She was..." Hall stutters, tenderly, "...she was beautiful." The personal attacks, the red-baiting, the invocation of her pink undergarments – it was all the idea of people like his campaign manager Murray Chotiner. Full of regret, Hall presents Nixon as a man haunted by an unrequited love, or a still-aching summer crush.

This was once more common, back when even his opponents shared Nixon's sense of himself as a tragic figure, his later fall as much a condemnation of where our politics were going as the character flaws inherent in the man who became president despite himself.

In his book Nixon Agonistes, published pre-Watergate in the middle of Nixon's first term as president, Garry Wills wrote about "the pathos of the man." In a preface to the 2002 reprint, he says that Nixon adviser Pat Buchanan complained that the book "played into the hands of the 'Nixon haters'", but points out that "the dedicated haters did not like the book. They were so convinced that he had no principles that they resented my saying that he did have principles, they were just outdated ones – the principles of market competition and classic liberalism."

"These were far from what people were calling liberalism by the 1960s – big government, compassion for the poor, tolerance of dissent. He was not a liberal in that sense. His liberalism was that of the Social Darwinians, and he was as outdated as those obsolete specimens. Others thought he had principles, but they were largely confined to anti-communism. These people were confounded by Nixon's opening to China (which almost made the National Review support a rival candidate in 1972.)"

Very far from Wills we had Neil Young, who wrote "Ohio" for Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young in response to the 1970 Kent State shootings – probably the last great anti-war protest song. ("Tin soldiers and Nixon's coming/we're finally on our own." I've never really understand what he meant, but it sounded ominous.) Six years later, on the eve of the Carter presidency, he was in a much mellower mood writing "Campaigner," which was released a year later on Decade, his three-album greatest hits package.

The song is explicitly about the former president – among other things. "Hospitals have made him cry/though there's always a free way in his eye," Young wrote, referring to Pat Nixon's recent stroke and the constant media scrutiny of the disgraced president: "though his beach just got/too crowded for his stroll."

The empathy is made even more explicit in the chorus, where Young sings about a place, one of his trademark art movie visions of America, "where even Richard Nixon has got soul." It was a remarkably gracious move for a leading light of the musical counterculture, but also a reminder that Nixon and Vietnam had declined considerably on his generation's list of priorities since the president ended the draft in January of 1973. By 1976, I guess Neil could afford to be magnanimous.

The meaning of the title Secret Honor becomes gradually explicit as Nixon talks about the Committee, Bohemian Grove and especially China. "The China Plan would be my Excalibur," Hall-as-Nixon tells us, adding that it would ultimately be "a pact with the Devil."

"I sold my soul at Bohemian Grove," he tells us. "For shit." The man who put all of his energy into becoming president, even after running and losing – "a slimy slug crawling toward the White House" – comes to realize that the plan in which he has such a central role is ultimately about the death of the Republic.

As Hall's Nixon explains it, he was supposed to turn his landslide 1972 win into a "Draft Nixon" movement in 1976, overturning the 22nd Amendment and ultimately leading to a fascist takeover of the country by 1980. Nixon's opening up of relations with China would transform whoever sat in the Oval Office into a "President of the Pacific Rim" – the ultimate goal of the winners on the Committee, for whom Asia was a huge new market and a Free Taiwan, somehow, the linchpin.

(In real life, this has turned out somewhat differently.)

But this was too much even for Tricky Dick, who decided to run a diversion – to "orchestrate the tapes" and "lead the press and the congress to the tip of the wrong iceberg." He had to choose secret honor – and public shame.

"John Dean – I would have had to invent John Dean!"

Finally unburdening himself of the truth, Hall's Nixon is confronted with a vision of his Quaker mother again, like Hamlet and his father's ghost. This time she beckons him with instructions; he makes his way to his desk, points to the revolver and then picks it up, the muzzle touching his temple. At the last minute, though, he tosses the gun down, saying that they won't make him do it, even though that was the plan.

"F--K 'EM!!" he shouts, pumping his fist in the air, the moment captured on all four CCTV screens, turning into a loop while in the background a chant of "Four more years!" is brought up in the mix until the screen glitches and goes black. For a few moments, you really need to process just what kind of craziness the film has just laid out for us.

It's a hell of an ending, and I remember being breathless as I watched it as a college student, at a screening at the Toronto film festival. There have been a lot of Nixons on film – Anthony Hopkins' underplayed take in Oliver Stone's Nixon, Dan Hedaya's twitchy cartoon in Dick, Frank Langella's sinister Nixon in Frost/Nixon – but Hall's Nixon, desperate, contrite, spouting a nearly Tourettes-like stream of obscenities, remains my favorite.

It should have been a career-making performance for Philip Baker Hall, and ultimately it was – but only after word of mouth slowly built in the years following the film's subdued release into film festivals and art houses. Paul Thomas Anderson, a young director and Altman acolyte who says Secret Honor is one of his favorite movies of all time, cast Hall in many of his films, beginning with Hard Eight, Boogie Nights and Magnolia.

Robert Altman would ultimately make his triumphant return to Hollywood, beginning with Vincent & Theo in 1990. But it would be The Player in 1992 that made him, well, a player; there's nothing Hollywood loves more than a movie that portrays it as a moral charnel house, especially when it's a hit. He was a hot property for the critics again, making a big-budget film featuring major stars – Short Cuts, Pret-a-Porter, Kansas City, Dr. T & the Women, Gosford Park – nearly every year until his death in 2006.

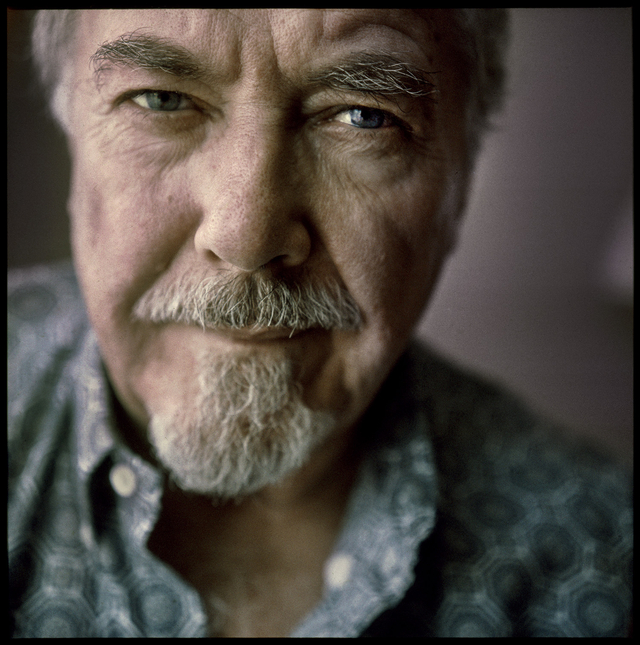

I photographed Altman in 1990, just when his exile was ending, at the Toronto film festival. Making small talk while setting up my camera, I told him that he had made one of my favorite films of all time, and that I was pretty sure he couldn't name it.

This obviously intrigued him – a response I was hoping for, as the director had a reputation for being difficult and cranky. He began listing a series of his more obscure titles.

"Quintet? HealtH? Tanner 88?"

No, I said. Secret Honor.

"Oh," he said. "That is a strange choice."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.