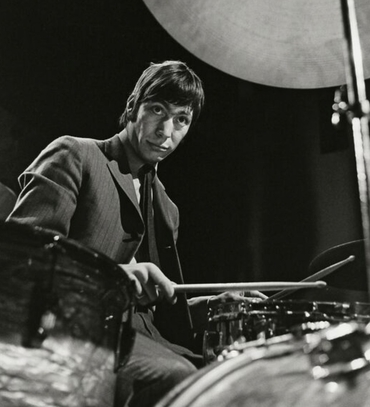

This week, I want to take a break from my ongoing rambles on Wokism to pay tribute to a musician I've always admired: Rolling Stones drummer, Charlie Watts, who died yesterday.

In a previous piece, I described Led Zeppelin's John Bonham as the overall rock drummer par excellence. Extraordinarily dynamic, Bonham had a lot of gears. He could play louder and heavier than anyone, but could also finesse quiet passages, zig-zag between funk and reggae and swing, and, well, you get the picture.

Charlie was a different sort of drummer, at least while playing with the Rolling Stones. If Bonham was a six-gear, $100,000, 230 horsepower, hot-rodded Harley (with Batmobile-style mods like a smoke-blower, mini-machine guns, and oil-slick dispenser), Charlie was your English grandfather's vintage Raleigh bicycle. It never broke. It was easy to maintain. You could cruise along on it all day long year after year, decade after decade. It had only one gear, but for a bicycle, it was the perfect gear. And it is with drummers and vehicles as it is for everything else: horses for courses. Which one's best depends on what you need.

And what the brand new blues band, the Rolling Stones, needed on drums in late 1962 was solidity. Constancy. No frills. Reliability. Maturity. That sort of thing. The eager band members were all teenagers, after all. Their nineteen year old singer Mick was hyperactive, teeming with ambition, but unsure about direction. Their guitar player, Brian, was flighty and aloof. Their other guitar player, Keith, was a young colt—naive and still unformed. The bass player, Bill, could barely play. In fact, the entire band could barely play. What they needed, in short, was the musical version of that durable, vintage Raleigh to get them where they needed to go.

Translation: What they needed was Charlie Watts. They got him in early 1963, when he joined up. And at a couple of years older than the other guys, he even had that extra bit of maturity they needed.

In the space remaining, I just want to mention a few of the more endearing things about Charlie.

First, you might never guess, listening to his recorded Rolling Stones drum performances, that Charlie was a precocious jazz drummer. With the Stones, he was a paragon of percussive minimalism. In fact, I'm not sure there's a single drum fill on any Stones song a five year old couldn't play.

But that's no sleight. What matters is playing the right thing—not the complicated thing—and as it happened, Charlie always played the right thing. He played what he played because that's what he should have played in the Rolling Stones song he was playing. That's what good musicians do, after all.

Consider the lead-in fill for "Gimme Shelter" (at :40). It consists of simple snare hits on beats three and four—bap - bap—and he's in. And what's great is, his big "variation" on his lead-in two hit fill, a few bars later at :47, is just a four hit fill: bap - bap - bap - bap.

And then, he just keeps the same quarter-note thing going every time the song calls for a drum fill. The fill at 1:04 is the same couple of snare hits on three - four that we heard in the original lead-in fill. ("After all, this quarter note bap - bap thing is working", I can imagine him thinking. "Why change it?"). Another quarter-note pair at 1:10, and then 1:19. Then at 1:36, then 1:44, then 1:52, then 2:00, then 2:17, 2:24, 2:32, 2:40, 2:48, 2:56, and 3:05. It's the same fill every time. The first real variation we get is that instead of hitting the snare on three and four at 3:13, he hits it on (three) AND - (four) AND. We get another variation at 3:23, then variations (albeit simple variations) for the rest of the song. By then, of course, the song is reaching its climax. Everyone's loosening up, so the drummer loosens up a bit, too.

But the important thing is that by then, we've already had over three minutes of Charlie's simple quarter-note fills forming an important part of the song. You end up waiting for his bap - bap chorus set-up as much as for the chorus itself, because the bap - bap serves as the Skinnerian bell to signal the imminent return of the chorus (the aural payoff).

Or consider the lead-in fill to "Honky Tonk Women" (at :04). It is a reprise of the (three) AND - (four) AND hits he played at 3:13 of "Gimme Shelter". It's just two drum hits. Very simple, but the perfect little drum introduction. The rest of the song is a typically deadpan performance. Few fills, no ride cymbal, and only two crash cymbal hits in the entire song: on the very first downbeat he plays (at :04) and then, on the very last beat of the song (at 2:53). The result? A classic rock and roll song still going strong after half a century.

"Miss You" features another characteristically focused drum performance. Mick cuts loose, rapping and improvising, moving in and out of falsetto. The guitars, harp (harmonica), sax, bass, and piano all play quite freely. But underneath it all, Charlie pumps along, solidly in the groove.

This is the key to every Rolling Stones song. Charlies never breaks character. He starts the song, pumps along underneath, hits the fills where needed, but never plays a single gratuitous note. Then the song ends. Then he starts a new one. On it goes. As each song begins, everyone else hangs on, so to speak, to his chugging rhythm. It's no wonder Keith once said "Charlie Watts is the Stones".

On that note, I should mention one famous quirk of his drumming style. In most rock and roll songs, drummers will play eighth notes on their hi-hat with their right hand, while underneath, their left hand hits the snare drum on the backbeat (beats two and four). For that reason, on beats two and four, the drummer will be hitting the hi-hat and snare simultaneously.

But not Charlie. He's the only drummer I know of who, as a general rule, rests his right hand (not hitting anything) every time his left hand hits the backbeat. You can see this here, at :34, for a few seconds. The effect is a snare sound unclouded by an additional hi-hat sound—that is, what you get is a highlighted, or accentuated, snare hit.

I suppose I should disclose here that I'm not unsympathetic to the 58 years worth of conservative concerns over the Rolling Stones as a cultural force. In particular, it's hard to see how Allan Bloom's hilariously cantankerous tirade against Mick Jagger in The Closing of the American Mind is far wrong. For Bloom, Mick represented a cynical satyr who corrupted the souls of young Rolling Stones fans for filthy lucre. He legitimized drug use. He legitimized libertinism. He legitimized an androgyny which heralded and promoted deeper, darker, forthcoming societal fissures. He even legitimized full-blown antinomianism itself—a rebellion against all law, all tradition, all standards, all morality. When it came to the "weak and ordinary", wrote Bloom, "Mick Jagger played the role in their lives that Napoleon played in the lives of ordinary young Frenchmen throughout the nineteenth century".

All of that and more could be true, with it also being true there remains a lot to admire about a lot of Stones songs (say, "Wild Horses", "She's a Rainbow", "Angie", and others), and in Charlie Watts's unique playing in particular. I heard Arkansas governor (and pastor) Mike Huckabee say the same thing once, and I've always thought he was right.

Aside from music, I understand Charlie was a wonderful chap. One friend of mine—a musical minor-leaguer whose band just happened to play the same festival as the Stones one day three decades ago—happened to bump into Charlie backstage at the show. Within a few minutes of chatting, they discovered they shared a mutual fascination with the paintings of Marc Chagall. To my friend's astonishment, the conversation evolved into a genuine friendship which lasted for years. That Charlie was A-List, and my friend somewhere around the P- or Q-List, didn't matter to Charlie. I've heard the same sorts of stories from various folks over the years.

In any case, I just wanted to pause to acknowledge the passing of Charlie Watts, one of the few true gentlemen in rock and roll, one of the great all-time drummers, and a true one of a kind. May he rest in peace.

Mark Steyn Club members can weigh in on this column in the comment section below, one of many perks of club membership, which you can check out here.