Written on the Wind was the zenith of director Douglas Sirk's career in Hollywood, based on both box office and style. The 1956 melodrama – probably the greatest that Sirk made – is relentless and hyperbolic, lunging out at us from the first shot, laying on the malice and tragedy and dysfunction with every scene.

It was the first Sirk picture I ever saw, in a backroom music club on Toronto's then-hip Queen Street West strip. Back then the cool kids were supposed to be into books and movies as well as music, and someone programmed a film retrospective at the Rivoli that featured Sirk, no doubt inspired by how "transgressive" filmmakers like Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Pedro Almodóvar, David Lynch and John Waters (and later Todd Haynes, Quentin Tarantino, Guillermo del Toro and Wong Kar-wai) acknowledged his influence.

What I remember is not knowing if the audience was laughing at or with the movie; it was still a time when lurid Technicolor weepies from the '50s were kitsch, and Sirk's films were prime examples of the genre. Today they've been wholly rehabilitated by people who love movies, though I'm sure that casual young moviegoers – the sort of people disparagingly described as being at sea with films made before the Star Wars prequels – would find them baffling, unable to even giggle at the overcooked drama.

You need a sense of what middlebrow culture looks like to recognize kitsch – knowing or accidental – and the decimation of the middle in favour of an overwhelming mass culture and a tiny, nearly insignificant high culture has made that impossible today.

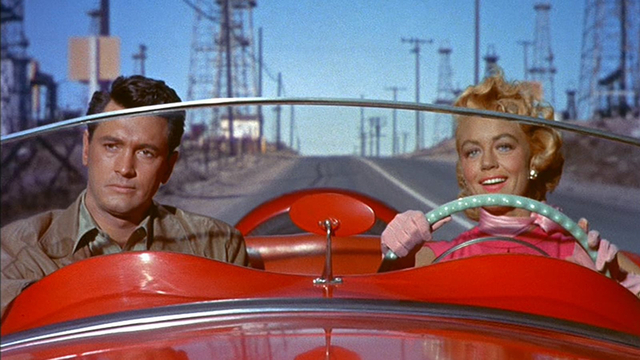

A yellow sports car explodes out at us; in the driver's seat Robert Stack tugs the cork out of a bottle with his teeth. The car roars past fields of oil derricks and pumpjacks, through a town closed for the night, until it skids to a halt in front of a gated mansion. Upstairs Rock Hudson notices his arrival with agitation; on a bed nearby Lauren Bacall languishes in pain. In another window Dorothy Malone looks down, anticipating something avidly. At this point the soundtrack switches from Frank Skinner's lugubrious score to the Four Aces' woozy, delirious rendition of Sammy Cahn and Victor Young's title song.

Stack staggers from his car, throwing open the front door of the mansion, filling the vast foyer with leaves blown in by the tempest outside. He enters a room; Hudson and Malone follow him. There's a sudden silence, then a gunshot. Stack staggers back outside and collapses to the ground. In the window upstairs Lauren Bacall swoons and faints, and the wind blows the pages on her desktop calendar backwards – months, then a year, then further, to a dissolve that finds the calendar on a desk in a New York City office tower. Everything that happens from this point on is a flashback, to an outcome we all know.

Lucy Moore (Bacall) is a new executive secretary in the marketing department of Hadley Oil, and her first important visitor is Mitch Wayne (Hudson), the childhood best friend and "sidekick" to the company's heir apparent, Kyle Hadley (Stack). He's flown into Manhattan because Kyle had a hankering for the steak sandwich at "21", and flirts with Lucy by inviting her along. It doesn't go according to plan; his rich friend takes a liking to Lucy, and invites her on a spur of the moment trip to Miami, where he fills an ocean view suite with clothes and gifts – a tactic that's obviously worked before.

After a moment of temptation she flees, but Kyle tracks her down to the airport and convinces her to listen to part two of his sales job – the part where he confesses his fears and insecurities. It works; they get married in Acapulco, and Mitch barely overcomes his disappointment when it seems that Lucy has arrested his friend's drunken slide to self-destruction. But he has other things to worry about – Mitch's sister Marylee (Malone), a sultry blonde who hates her brother, mostly because primogeniture and gender has given him the privilege of escaping the place named after their family and its company.

Hadley, Texas is an oil town, where everyone works for the company, whose logo is branded on nearly everything in sight, and where everything seems to happen within sight of a field of Hadley oil derricks. Among other things, Written on the Wind is one of those very American oil stories, in the lineage of Giant, Dallas and There Will Be Blood – a tale of enterprise and arrogance, where the fortune wrung from the Earth poisons the family who made it in a generation.

Something is very wrong with the Hadley kids, and there's nothing Lucy, Mitch or the kids' father Jasper (Robert Keith) can do about it. After a year on the wagon, Kyle is frustrated that they can't have kids; at first he thinks it's Lucy, but the town doctor informs him at the pharmacy soda stand that he's been diagnosed with "a...weakness."

This is the scene that's remained in my memory since I first saw the film over thirty years ago in that little rock club. Kyle ignores the doctor's insistence that the prognosis isn't hopeless as he rises up from his chair and walks heavily out the door. Just outside the pharmacy a towheaded boy is riding a coin-operated mechanical horse, rocking away with blissful, idiot glee as Stack glares at him with resentment and regret. This made the audience at the Rivoli burst into laughter.

Marylee has carried a torch for Mitch since they were kids – an unreciprocated passion that sours even more when she intuits that Mitch is carrying one for Lucy. The dialogue between the women after the newlyweds return from their honeymoon is a melodramatic masterclass; Lucy picks up on her sister-in-law's antipathy quickly, but her attempt at a curt dismissal is parried sharply by her new enemy:

Lucy: Pardon me if I seem to be brushing you out of my hair.

Marylee: I'll send you some of my towels – you still seem to be little wet behind the ears.

Maybe there's some place where people talk like this, but I doubt if I'll visit it while I'm alive.

Sirk admitted later that he didn't consider the "heroic" half of his quartet of leading characters very interesting, calling Mitch a "negative figure" and Mitch and Lucy "rather coldish people." This was, he said, intentional, and he cast Bacall in particular "because she has this ambiguity in her cold face...people asked me why I didn't cast a nice sweet American girl. But I wanted what Bacall has. She has this wavering light about her – and she is not a lover."

Kyle and Marylee, by contrast, are compelling despite their horrible flaws; they leave behind a path of destruction, but your eyes are constantly drawn to them. Malone in particular tears into her role with crazed intensity. As her brother falls spectacularly off the wagon – he's carried home from dinner at the country club, draped over Mitch's shoulders – she seizes her chance to wreak real vengeance.

The sheriffs have fetched her from the motel where she checked in with a gas pump jockey she picked up; while the boy is brought into her father's office, she saunters by without a look back, dragging her fur stole across the floor. In her room she puts a mambo on her record player, picks up a framed picture of Mitch and changes into a red chiffon negligee, dancing the whole time – a frenzied, convulsive dance that Sirk cuts with increasing tempo between her father, trying to recover from this final humiliation, and Marylee's legs and arms, torso and derriere, thrusting through the frame and toward the camera.

In his book Movie Love in the Fifties, writer James Harvey calls it her "totentanz" – a furious performance that seems to drain the life out of the old man as he trudges up the grand staircase of the mansion, faltering near the top and toppling dead to the bottom. Her wicked deed done, she flings herself back on a sofa, scissor-kicking her bare legs with unrestrained joy.

Harvey observes that Marylee isn't "just a nympho (her usual designation in descriptions of the film) or a tramp or a spoiled rich girl, but a rather seriously bad person...But then the pure outrageousness of the sequence really undercuts that point, making it impossible to feel such a conventional moral judgment of her, even if it's the (at least partially) intended one."

"The scene is just too thrilling, too much fun to watch: the audacity of it can make you laugh out loud with satisfaction and pleasure." This might be the best description possible of how and why you enjoy a Sirk melodrama.

After her father dies, she turns to making her brother believe his wife is having an affair with Mitch. Kyle – Stack's sweaty, eye-rolling, bandy-legged performance as a drunk is one of the greatest ever filmed – is a fertile field for suspicion, pickled on corn liquor and anything else at hand, but even he is unwilling to believe her at first:

Kyle: You're a filthy liar.

Marylee: I'm filth. Period.

With dialogue this blunt, it's easy to see how people could miss all the subtleties Sirk tucks into nearly every frame of his pictures.

The movie after this is a cascade of calamities. Lucy gets pregnant but Kyle, his mind poisoned by his sister, is certain that it's Mitch's baby and hits his wife, who miscarries. His best friend beats him soundly, threatens to kill him and kicks him out of his own house, leading back to the scene we witnessed in the opening credits, minus the detail that it was Marylee who accidentally kills her brother, trying to wrestle away the gun he points at Mitch.

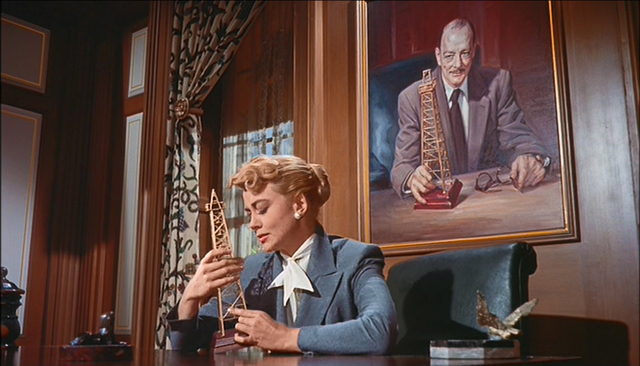

After failing to blackmail Mitch into marrying her, she nearly incriminates him for murder at the inquest, only to have a sudden – frankly unbelievable – pang of conscience, telling the truth. The film ends with Mitch and Lucy driving away from Hadley, Hadley Oil and the Hadley mansion while the last Hadley – Marylee, in a comparatively sober and beautifully cut business suit – sobs at her father's desk, beneath his portrait, stroking the model of an oil derrick she picks up from his desk.

Your first thought is that Hadley Oil is in good hands now, as Marylee is doubtless as ruthless a chairman as the company could ask for. The second is that what looks like a phallus is, sometimes, really a phallus. Why would you expect subtlety after everything else we've seen?

Sirk made several pictures a year, and liked to work with the same people if he could – George Sanders and Linda Darnell early in his Hollywood career, Barbara Stanwyck in the '50s, Hudson and Jane Wyman in Magnificent Obsession and All That Heaven Allows, and the trio of Stack, Malone and Hudson just a year after Written on the Wind in The Tarnished Angels.

Based on Pylon, a William Faulkner novel, Sirk had been trying to make a movie version since he'd read it twenty years earlier. He got his chance thanks to the success of Written on the Wind, and thanks to Albert Zugsmith, his producer on both pictures at Universal. Known mostly for overseeing smutty trash – Zugsmith was the producer on The Incredible Shrinking Man, Fanny Hill and Sex Kittens Go To College as well as Orson Welles' Touch of Evil – they had a working relationship that left Sirk alone to do what he wanted, though the director once joked that he had to stop Zugsmith from changing the title of The Tarnished Angels to Sex in the Air.

Faulkner's story about barnstormers performing at a fair during the Depression was cast with Stack as Roger Shumann, a former WWI ace and member of the Lafayette Esquadrille, Malone as his wife LaVerne, a parachutist in his act, and Jack Carson as Jiggs, their mechanic. Hudson returned as Burke Devlin, a reporter at the New Orleans Picayune who falls in with the trio looking for a human interest story. (This is one of the few times I can recall the name of a real newspaper being used in a film that isn't All the President's Men.)

Even more than her previous picture with Sirk, The Tarnished Angels belongs to Malone, an underrated actress. Very different onscreen when she was a brunette – let's not forget her as the sexy and knowledgeable bookstore clerk in Howard Hawks' The Big Sleep ("You begin to interest me, vaguely.") – she returns sporting Marylee's platinum tresses, but she's much more vulnerable here, married to a man who'd barter her to a fat tractor manufacturer for a few hours to get a flyable plane.

Malone's LaVerne is the object of desire for nearly every man in the picture, jumping out of Stack's plane in a diaphanous white dress and flats, walking back to the hangar after landing on the sand like she's on her way to lunch at a resort. You wonder how she ended up in such a hopeless situation, and even when she tells her story to Burke late one night, it still seems hard to believe. Looking like a vamp – a Marylee Hadley in more desperate straits – she's more of a prisoner of her looks – not bad, as another film described its female lead, but just drawn that way.

Sirk said that the films were linked by "the same mood of desperation, drinking and doubting the values of life, and at the same time almost hysterically trying to grasp them, grasping at the wind. Both pictures are studies of failure. Of people who can't make a success out of their lives."

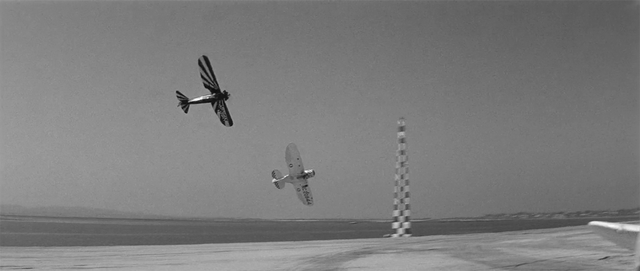

In Movie Love in the Fifties, James Harvey says that "the movie seems – in spite of the action, the plane races and crackup scenes – becalmed, its mood a kind of choked desolation (Stack remarked later that at least it did very well in Europe), its main action the aggrieved and damaged characters circling each other warily and talking, in shabby diners, half-lit apartments, empty airplane hangars, while a distinctly sinister Mardi Gras (the locale is New Orleans) goes on outside."

Though he later tried to say it was his idea, Sirk was forced to shoot The Tarnished Angels in black and white to save money, and without his usual cameraman, though he admitted that he wasn't comfortable with the super widescreen CinemaScope framing, but it doesn't matter. The film is beautiful – one of Sirk's most striking pictures, and not just when the epic panoramic frame chases the old planes as they race over the water and past the carnival rides.

Despite the luminous austerity of the camerawork, it's surreal, even for a Sirk picture, with the citizenry on a collective bender, dressed in costume even when there isn't a parade around, some of them sporting crude papier-mâché masks that give us a peek at the nightmare lurking beneath everything.

And it has that ambiguous Sirk ending, a dubious feint at resolution and even happiness for the characters left standing, undercut by the relentless mood established over the last ninety minutes. It was a flop, and audiences who went expecting to see Hudson in a starring role might have been disappointed by his very secondary part in the story, as a man more tentative and unsure of himself than in his usual heroic parts. It was the last of eight films he did with Sirk, who helped make him a star. He'd still have a long career in Hollywood, but Sirk's was nearly at an end.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.