The worst thing about critics – thankfully not anything worth worrying about since there are few jobs more essentially useless – is the way judgments made under deadline or the influence of fashionable assumptions can stand for decades, interfering with how we discover or rediscover art. There is a lot to be said for the immolation of a critic's opinions with their earthly remains on their funeral pyre.

It was this sort of critical "consensus" that unfairly maligned melodramas for decades, most crucially when the genre was at its peak in the '50s – precisely when they were dismissed out of hand for being merely "women's pictures." Doing this today would be suicide for a critic's career, and explains why melodrama – emotionally intense domestic dramas built on overdrawn social conflicts and improbable coincidences – is now at the core of most TV dramas (both network and on quality cable streaming channels) and even superhero stories.

The master of the Hollywood melodrama was director Douglas Sirk, mostly because of about a half dozen films he made in the '50s, which became touchstones for directors who celebrated his influence in the decades that followed. As influential as they might be, those films can be tough going for audiences today, most of whom have a hard time seeing past the (admittedly and intentionally hypertrophied) period detail.

Sirk was born Hans Detlef Sierk in 1897, to Danish parents living in Hamburg, Germany. Sirk had established himself as a notable theatre director when the Nazis took power in 1933; his second wife was Jewish, and he knew that they would need to leave the country. Judging his theatre resume to be of limited use outside Germany, he obtained a position at UFA, the country's preeminent movie studio, and worked on a series of films that eventually gave him an entrée to the United States and Hollywood. By 1942 he was under contract to Columbia Pictures.

The first half of Sirk's career in Hollywood gave no hint at all that he would become the master of widescreen melodrama. His first picture was Hitler's Madman (1943), a propaganda B-film starring John Carradine. He would follow it up with film noir (Lured, Sleep My Love, Shockproof, Thunder on the Hill), comedy (Week-End with Father, No Room for the Groom, Has Anybody Seen My Gal?, Take Me To Town) and even a couple of musicals (Slightly French, Meet Me at the Fair) and a 3D western (Taza, Son of Cochise), the latter featuring a young Rock Hudson, who would become Sirk's favorite leading man.

What this journeyman filmography did produce was a vivid, visually confident style that Sirk would use to great effect on his melodramas. By the time he signed a contract with Universal, he had taken the expressionism that was artistically in vogue in Germany during his formative years and made it bloom in an American setting with deep focus widescreen and the unreal hues of Technicolor. Sirk's melodramas have an epic feel that's surprising in domestic dramas; loaded with symbolism, they have a disorienting, dreamlike feel. This montage gives some sense of how they must look to someone – a millennial, perhaps – who's never encountered cinema like this before.

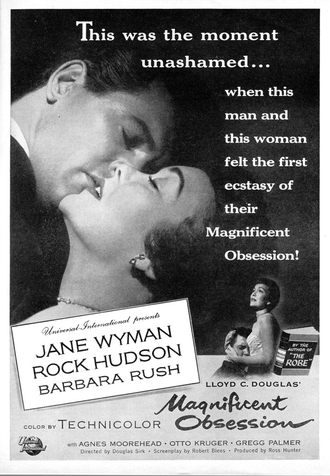

Sirk's dominance of melodrama begins with All I Desire, a 1953 period romance starring Barbara Stanwyck, but his first masterpiece in the genre is Magnificent Obsession, released the next year. Rock Hudson plays Bob Merrick, the playboy heir to an auto fortune who we see roaring across a lake in a racing speedboat until his cockiness leads to an inevitable crash. When paramedics struggle to save his life, they borrow the resuscitator from a local doctor who has an ill-timed heart attack. Merrick finds himself in the doctor's clinic, where he's baffled why the staff are so rude to him – his own habitual callousness apparently doesn't register – until he learns that he was the likely cause of their much-loved boss' death.

Technically Hudson's Merrick is the protagonist of the film, as the story is his journey from shitheel to saint, but Magnificent Obsession never loses its focus on Helen, the doctor's widow, played by Jane Wyman. Spurred by guilt and an encounter with the painter Randolph (Otto Kruger), the late doctor's best friend, Merrick learns how Randolph and his friend lived their life by a code of good deeds and anonymous charity. He clumsily tries to move down this path, throwing money around and barging into people's lives, until he barges a bit too hard into Helen's and causes an accident that blinds her.

Mortified, he decides to return to medical school. He's also so transformed that he's able to insinuate himself into Helen's life, pretending to be "Robby", a poor student who reads to her on the beach near her house. He arranges for Helen to go to Switzerland for treatment, but the doctors there can't offer any hope. During a romantic evening where they witness the festive burning of a straw witch in a nearby village – sometimes the symbolism in Sirk's films defies explanation – he reveals his true identity and proposes to her. She says she knew who he was and accepts, but flees the next morning, afraid of being a burden.

While Hudson's Merrick does the lion's share of the film's character development, Jane Wyman's Helen simply suffers, albeit beautifully. There's an implied age gap between Robby and Helen – the actors were born only eight years apart, but Hudson was in the early prime of his matinee idol stardom, while Wyman had been in movies since the early '30s, playing in endless "B" pictures at Warner Bros. before a role as a raped deaf-mute in Johnny Belinda (1948) won her an Oscar and made her a star.

In Tom Ryan's recent book on Sirk's career (The Films of Douglas Sirk: Exquisite Ironies and Magnificent Obsessions) he notes that "Wyman...who gives a performance that is both dignified and heartbreaking, always looked older than her years and seemed well-equipped to deal with whatever crises befell her characters." There was nothing of the ingénue or femme fatale about Wyman, and her look in Sirk's films was definitely that of a mature woman, not quite matronly despite her tiny nose, apple cheeks and tight, short curls and bangs.

Wyman's key scene – and the one that reminds us why Magnificent Obsession is really about her and not Hudson – is at the Swiss clinic where she's given the bad news. The team of kindly white-haired doctors are clearly pained to dash her hope, but it's all in the way Sirk's camera moves around and closes in on Wyman while she processes what they're saying. We see every optimistic scenario she imagined dissolve as she finally resigns herself to a sightless future.

Sirk liked to work with the same actors when he could, so when Magnificent Obsession was a hit, Wyman and Hudson (and Agnes Moorehead, once again playing Wyman's best friend) returned together for All That Heaven Allows a year later, between which Sirk actually finished two other pictures - a historical drama featuring Jack Palance as Attila the Hun (Sign of the Pagan) and an adventure film starring Hudson as an Irish revolutionary and highwayman (Captain Lightfoot).

Unless you are a diehard Sirk completist, I do not recommend tracking down either film.

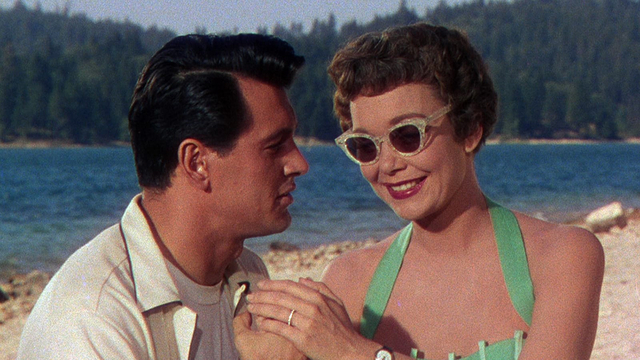

All That Heaven Allows is another May-December romance (though technically it's more June-September). Wyman plays Cary, another widow, who begins an affair with Hudson's Ron, her hunky gardener. There were still publication bans on Lady Chatterley's Lover at this time, so it's fun to speculate that Sirk's film is what a very censored film adaptation of the D.H. Lawrence novel would look like, though the source of the film was actually a far less risqué (or notable) novel by Edna L. Lee and her son Harry.

The credits roll over an overhead shot of a church steeple and clock tower and pan down the wide lawns and generous houses of Stoningham, Connecticut – one of those prosperous commuter towns that embodied the better zip codes of the postwar economic miracle, looking especially perfect through a lacework of red and yellow autumn leaves. It's a shot that Sirk returns to in different seasons throughout the film, underlining the setting as significant, though we quickly learn that despite its postcard-perfect quality, it's really a prison for Wyman's Cary.

The chemistry between Wyman and Hudson is much more palpable this time – Wyman's Cary even looks younger, and Hudson's Ron is neither a heel nor a hero but a man who Cary's friends either openly ogle or describe as "nature boy." At a disastrous dinner party, the town gossip remarks on Ron's tan: "I suppose from working outdoors," she says, adding "I suppose he's handy indoors, too." Ron makes appreciative comments about Cary's legs, and as Wyman was once a chorus line dancer, they're worth making. Sirk insists we believe that the characters have hard-ons for each other, and they have to if the story is going to work at all.

The conflict in the film is between Cary and everyone whose opinion matters to her before she meets Ron – her country club social circle in Stoningham and her college age children. Except for the kindly town doctor and Moorehead's Sara, her so-called friends are a dire lot – blowhards and shrews, a lecherous lout and plump older women who look like runners-up in a Margaret Dumont lookalike contest.

But the real villains are her children, a truly intolerable pair who object to her romance with Ron immediately. Sirk portrays them with unconcealed contempt: her son is a pompous Ivy League drone whose only apparent virtue is his skill at mixing martinis, while her daughter is an aspiring social worker who spouts whatever nonsense she's picked up in a lecture hall or common room that week, from Freud to pre-Friedan feminism. Describing her work in New York City, she proudly coos that "you meet all kinds of people." Both of them think their mother should give up Ron and get a television set. They're adult children, in the fullest sense of the term, and we are still afflicted with their kind today.

They're contrasted with the crowd Cary meets at a potluck dinner, hosted by Ron's friend and fellow Korean War vet Mick and his wife Alida in their flat over the office of their plant nursery. Ron and Mick and Alida are whatever one assumes might pass for bohemians in midcentury rural Connecticut – if your idea of beatnik style involves mismatched club chairs. The party guests are eccentric geriatrics and swarthy "ethnic" types, and they dance to calypso and vaguely peasant polkas after devouring a lobster boil and several straw-wrapped bottles of Chianti.

Alida tells Cary that Ron helped her husband find himself after they nearly divorced, when the couple worked unhappily in advertising in NYC. Cary picks up a copy of Thoreau's Walden and Alida says that she's not sure Ron ever read it, but that he "just lives it." Hudson's Ron looks like a proto-hipster today with his flannel work clothes and beat-up woody station wagon, and this is embodied in the old mill that he fixes up in hopes that it will be their home after he and Cary get married.

It's the hothouse space where their attraction takes root, a dusty ruin that Ron transforms into a rustic but sophisticated showpiece, with a huge picture window looking out over his land. Ron might look like an outsider to Cary's children and her hateful social circle, but as Tom Ryan points out in his book, Ron and his friends are harbingers of future social trends, like the "bobo" or bourgeois bohemian that New York Times columnist David Brooks identified in the '90s – creative professionals who gentrified urban neighbourhoods that Boomers overlooked, and would migrate to bedroom communities with excellent school districts like Stoningham.

"Certainly, within a generation," Ryan writes, "the value of (Ron's) land and property will increase well beyond that of the suburban real estate owned by the likes of Cary's social set."

The particular circumstances of Ron's outsider status and the pressure Cary feels to end their engagement might seem strange today, but what hasn't changed are social dynamics that allow the opinions of the worst people to set standards for everyone else – amplified by the hellacious din of social media. As Cary tells Sara after her friend warns her that their friends won't accept Ron, "situations like this bring out the hateful side of human nature."

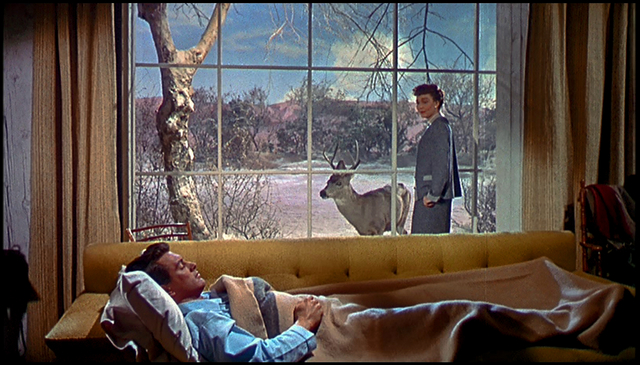

Of the two films, I prefer All That Heaven Allows to Magnificent Obsession, mostly because Sirk had more at stake when selling Wyman's attraction to Hudson. The earlier film is more precise and spare, with its clean, bright hospital and clinic sets. All That Heaven Allows by contrast looks lush, even fevered, with its extravagant studio recreations of fall and winter and aggressive lighting that renders adjacent spaces cool or hot.

Both films end with one of the lovers at death's door, lying on a sickbed, just barely revived by the effort and proximity of the other. But All That Heaven Allows makes it a euphoric moment, with a deer wandering into view through the picture window behind Ron and Carey, just as Ron's eyes flutter open. It's outlandish and surreal, and absolutely appropriate to a story where emotions have been fighting repression from very nearly the first shot.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.