Writer Paddy Chayefsky was near the end of a decade-long slump in his career when The Hospital was released in 1971. Comes the time, comes the man – America was in turmoil as the social and political tumult of the '60s looked to be metastasizing into something bleaker and perhaps permanent with the new decade. Chayefsky was a writer known for eloquent and ambitious takes on personal despair, and the zeitgeist allowed him to broaden his loquacious and angry monologues to include a broader panorama – a society having a nervous breakdown.

Sidney "Paddy" Chayefsky was the child of Russian Jews from the Bronx, a brawling, hyperarticulate bully who began his career in the golden age of live television, before moving to the theatre and the movies. He'd been ricocheting back and forth between the two after his first great success with Marty, a TV drama that won him his first Oscar when it was made into a film in 1955.

It had been nearly eight years since The Americanization of Emily, a satirical anti-war film and box office flop starring James Garner and Julie Andrews, and Chayefsky had been wandering between TV and the stage, with occasional, short and disastrous stints on screenplays like the 1969 adaptation of Paint Your Wagon, the film that made the unfortunate assumption that Clint Eastwood should sing.

He still had his reputation and his connections, however, and when it came time to make his "comeback" in the middle of the death throes of the studios and the Hollywood youthquake, Chayefsky was able to assemble a production company and a deal that gave him total control over his script about suicidal depression overwhelming an eminent surgeon at a New York City teaching hospital.

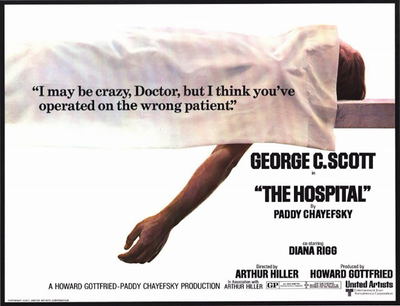

George C. Scott plays Dr. Herbert Bock, chief of medicine at a hospital where patients, nurses and doctors are dying at what would be a scandalous rate, if the hospital itself weren't under siege by activists and suffering the sort of institutional decline that inevitably overtakes any bureaucracy, in a city on its way to fiscal and social implosion.

Scott was fresh from the title role in Patton, a force of nature onscreen, and he plays Bock like a ticking time bomb, living in a cheap hotel after leaving his wife, drinking Smirnoff from the bottle and missing his rounds. After a brief comic introduction describing the latest lethal malpractice at the hospital – narrated by Chayefsky himself – we watch Scott's Bock as the bad news is broken to him.

Chayefsky did meticulous research for the film, and while his screenplay is an avalanche of medical jargon, hospital staff react to statements of simple facts with vaguely hostile indifference – like the sudden appearance of a young intern, dead in an empty bed, killed by the night shift ministrations of several nurses. It's a pitiless portrait of a classic bureaucracy, overstaffed but overworked and always far from the point of responsibility.

We wait for Scott to erupt, and it doesn't take long. Querying the head of nursing staff (Nancy Marchand – one of many small roles played by great actors in the film) on just how a healthy patient was rendered comatose in a week ("These things happen," she explains), he bellows "Where do you train your nurses, Mrs. Christie? DACHAU?"

My friend Kathy Shaidle and I always talked about Chayefsky, and particularly his masterpiece Network – the film he would make after The Hospital. Was it as good as it seemed the first time we saw it, and was it actually any good at all? Writing about Network here just over a year ago, Kathy marveled at Chayefsky's obvious talent and skill, and at the monumental thing he created with his words:

"In the same way that, when Terminator 2 came out, you could actually see (with a sensory satisfaction I've rarely savored before or since) every single cent of its then-record $100 million budget onscreen, you can feel Chayefsky's hard work here, but — and this is key — you are not distracted by it. You enjoy a simmering, simpatico sense of profound appreciation for his craftsmanship every second of Network's running time, while simultaneously remaining deeply immersed in the world he's created."

Chayefsky might be the first, and perhaps the only, screenwriter whose name appeared prominently on posters, and above that of the director on credits. Even after several years in the wilderness (actually Broadway and network television, with an apartment on the Upper West Side and an office in Midtown on the same floor as his friend Bob Fosse) Chayefsky was able to roar back into the cinemas with The Hospital, a movie that arrived amidst kidnappings, coups, terrorist bombings, hijackings, inflation, the invasion of Laos, the My Lai Massacre trial, Nixon's declaration of the War on Drugs, the publication of the Pentagon Papers, the famine in Bangladesh and the Attica prison riot like a backhanded slap, for those who bought a ticket.

And buy them they did – the film was a hit, and Chayefsky won a BAFTA, a Golden Globe and an Oscar for his screenplay. In the midst of what I remember, even as a child, as troubled, insecure times, audiences were mysteriously drawn to the dyspepsia and rage of The Hospital.

Chayefsky set about creating his story with purpose. He chose to film on location in Mayor John Lindsay's pre-bankruptcy New York City, saying that "the climate of hatred was energizing." But like most writers he didn't have to go very far to find the material to create Herbert Bock; autobiography had been the engine of his work since before Marty, and in Mad As Hell: The Life and Work of Paddy Chayefsky, Shaun Considine's biography, Chayefsky's son recalls:

"Up until nineteen-seventy, my father was going through the same self-torture as Bock," said Dan Chayefsky. "During those last five years of the nineteen-sixties, he felt absolutely useless. He had done everything in the business and if meant nothing. All he had wanted was approval and he found out nobody cared anyway, which made him more despondent."

George C. Scott's Bock is estranged from his wife and family, describing his son as a "pietistic little humbug. He preached universal love and despised everyone...He told me his generation didn't live with lies. I told him, listen, everybody lives with lies. I grabbed him by his poncho and dragged him the length of our seven room despicably affluent apartment and I flung him...OUT. I haven't seen him since."

He's also impotent – not just sexually but professionally, the spark of his once promising career diminishing every day. He reveals all of this to Barbara (Diana Rigg), the jaded hippie daughter of the man made comatose by his hospital, in an epic monologue that marks the midpoint of the film and the beginning of its switch from bleak drama to black comedic farce. She openly doubts both his suicidal depression and his impotence, provoking a classic Scott rage that climaxes with rape – the sort of scene once remarkably common in movies, a high stakes option on the menu of dramatic possibilities which audiences accepted with startling alacrity.

He wakes up the next day to Barbara saying she loves him, that he should leave with her and her father for their mission in the mountains of northern Mexico, and that she wants to have his babies. Bock - doubtless like many of us watching the film - finds this implausible:

"What do you mean I love you? I raped you in a suicidal rage. How did we get to love and children all of a sudden?"

Scott himself contributed much to Bock's belligerent, despairing character. He had left his wife, Colleen Dewhurst, for another actress, Trish Van Devere, was drinking heavily and was late for shooting when he showed up. As men, he and Chayefsky were far too similar, and this was always going to be a problem. Despite this the film was finished ahead of schedule and below budget.

Chayefsky was by this point as much a director on the film as Arthur Hiller, who officially had that job, and had directed The Americanization of Emily, Chayefsky's last produced script. He was a famous micromanager, supervising (or interfering in) nearly every detail of his films. After The Hospital was released, he even went around to neighbourhood cinemas in Queens and The Bronx to check on sound and make sure the projector lenses were clean.

It's hard not to watch The Hospital and anticipate Network, the film that will probably bear the burden of Chayefsky's immortality. There's the ongoing satire of the corporatization of America, and scenes where a hodgepodge of local activists – African-Americans, Puerto Ricans, feminists, liberal clergy, even young doctors from the hospital – besiege Bock's boss with a litany of demands while they occupy a block of condemned flats the hospital wants to demolish for a drug treatment facility.

Their barrage of radical jargon and hunger for network air time would be refined in the scene in Network where radicals and terrorists negotiate contracts, points and rights for The Mao Tse Tung Hour – probably the most indelible scene in the film besides the late Ned Beatty's "the world is a corporation" speech. It also echoes in the playbook for BLM and other professional activists today – proof that (as my friend Kathy loved to point out) satire rarely inhibits the object of its ridicule.

In the end, Bock decides not to escape with Barbara and her homicidal lunatic father to the mountains of Mexico, but to stay and try to keep the hospital running. It took a lot for him to ascend to the middle class, and for the middle class, duty trumps love. "Someone has to be responsible," he tells her. This makes The Hospital a reactionary film in radical times, but Chayefsky doesn't allow any illusions about success to slip through. "It's like pissing in the wind, right Herb?" says the hospital's chief as the two men trudge back into the failing institution. These are the last lines of the film.

Chayefsky used to brag that his research for The Hospital was so thorough that its biggest fans were doctors, and that "everything that happened in the picture happened in a hospital somewhere at some time."

But later, when he was suffering from the cancer that would kill him, he opted for chemotherapy instead of operations.

"No way. I won't let them near me," he told Eddie White, a friend. "He meant the surgeons," said White. "He had that terrible fear, 'They're going to get ahold of me and cut me up because of that movie I wrote about them.' He was concerned if they got him on the operating table he would not get up alive."

At the end, pleurisy necessitated a tracheotomy, and the last days of the man who had famously and endlessly talked and argued and shouted, and created dialogues and monologues that sounded more real than real life and more articulate than anyone could hope to be, died in silence, scribbling notes to his doctors, nurses, friends and family. His last one was written to his wife: "I tried. I really tried."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.