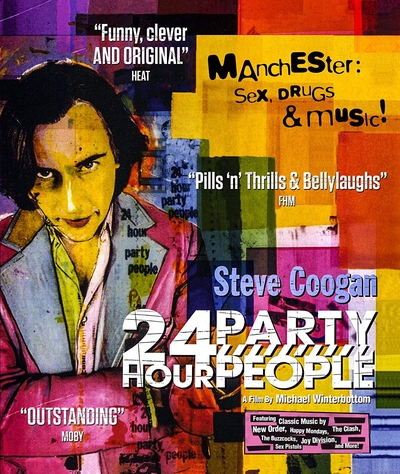

A chance encounter with a stranger on a street at night is a venerable movie cliché. Just such a moment happens at a key point in 24 Hour Party People, director Michael Winterbottom's very knowing, playful and dense 2002 film bio of UK TV presenter and musical entrepreneur Tony Wilson.

Wilson – comedian Steve Coogan in a performance that almost displaces the real Wilson for posterity – is walking down a rain-slicked empty street in Manchester, the capital city of Britain's post-industrial north, his life at an apparent crossroads. He passes a homeless panhandler – a cameo by Christopher Eccleston, best known to general audiences as the Ninth Doctor in the 2005 revival of the BBC's Doctor Who series. In exchange for spare change, the hobo/Timelord confides that he is Boethius, the dark ages author of The Consolations of Philosophy.

As Coogan-as-Wilson walks away from him, the philosopher bum expounds on the "wheel of fortune," one of Boethius' most lasting concepts, an explanation of history and fate. "History is a wheel," he proclaims, his voice echoing off the empty warehouse buildings.

"Inconstancy is my very essence," says the wheel. "Rise up on my spokes if you like, but don't complain when you're cast back down into the depths. Good times pass away, but then so do the bad. Mutability is our tragedy, but it's also our hope. The worst of times, like the best, are always passing away."

"I know," mutters Wilson, to himself and the camera. Later, when he becomes the host of a UK version of Wheel of Fortune (this never actually happened, though Wilson did host quiz shows like Topranko!, Remote Control and Masterfan) Wilson reprises Boethius for his TV audience. In the control room, the show's director curses him for going off script with a typical load of nonsense. The director is played by the real Tony Wilson.

24 Hour Party People is that sort of film. You either love it – as I do, passionately – or hate it, utterly.

Lying about Wilson as the compère of Wheel of Fortune is one of many – and among the least – of the liberties Winterbottom's film takes with the life of Anthony H. Wilson, who died in 2007 of heart failure while battling cancer, and who was complicit in the film's strategy, acting as "special consultant" on the picture and writing a novelization of the screenplay.

Early on in the film Wilson discovers his wife in the men's toilets of a nightclub, having sex with Howard Devoto, lead singer of influential punk/post-punk bands Buzzcocks and Magazine. He admonishes her for exceeding the apparently strict rules of revenge sex, then walks away and passes a man cleaning the bathrooms on his way out.

The man is played by the real Devoto, who turns to the camera and states that he has no memory of this happening. Coogan-as-Wilson then explains that it might be fiction, but that in a story like his the legend is always more appealing than the truth, and that he has always believed in director John Ford's motto that, faced with a choice, "print the legend."

A North American audience might wonder who Tony Wilson was, and why he deserves a whole film about him. A celebrity in the UK as a TV presenter, Wilson's real fame is among music fans. He was the man who started a record label that released music by the short-lived but massively influential Joy Division before the suicide of lead singer Ian Curtis triggered their metamorphosis into the chart-topping New Order.

He went on to open the Hacienda nightclub in Manchester and sign Happy Mondays, helping midwife the birth of rave culture and "Madchester," the turning point that transformed Manchester from an economically depressed northwestern industrial city into a centre for digital media and entertainment, restoring its status as the second most important city in England.

All of this comprises the story of 24 Hour Party People, beginning with the moment when Wilson, his first wife Lindsay and friend Alan Erasmus join forty other people in the Lesser Free Trade Hall on a night in June of 1976 to watch the Sex Pistols. In the audience were future members of bands like Joy Division/New Order, The Smiths, The Fall, Buzzcocks and (strange but true) Simply Red.

A junior presenter with a reputation for shameless self-promotion, Wilson goes all in with the new music, turning his own short-lived pop culture variety show So It Goes into a showcase for bands like the Pistols, the Clash, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Iggy Pop and the burgeoning Manchester punk scene. He also forms Factory Records with Erasmus, Joy Division manager Rob Gretton and producer Martin Hannett; it should have been the biggest record label in the UK, except for Wilson's appalling business acumen and a naive socialist insistence on no contracts except verbal ones between the artists and the label. A declaration that he (according to the legend) wrote in his own blood.

As portrayed by Coogan (and with what one presumes was Wilson's blessing), Tony Wilson is all ego, smarmy charm and billowing pretension, a man blessed with conviction that allows him to sail through walls of antipathy. The first time he meets his public and his label's future artists, at the opening of the Factory club night that will give his label its name, he's called a "wanker." Inside, Ian Curtis looms threateningly over him by a pool table and calls him a "c*nt."

Twice.

This is only the start of the abuse heaped upon Wilson throughout the movie by friends, fans and enemies. He's physically assaulted by Gretton at a Factory board meeting and has a gun pulled on him by both Hannett and Shaun Ryder, lead singer of the Happy Mondays

The UK advertising campaign for the film featured full-sized posters of the actors playing Ryder, Ian Curtis of Joy Division, and Coogan-as-Wilson. Ryder's likeness bore the word "Poet" – Wilson continually insists that the half-mad, often incoherent addict is the contemporary equivalent to W.B. Yeats – while "Genius" is printed across that of Curtis.

Coogan-as-Wilson bears the looping, cursive legend "Twat."

Throughout the film, Coogan breaks the fourth wall and explains the film and himself to the audience. At the end of the first scene – a re-creation of an actual report Wilson did for Granada News on hang gliding – he points out that what we've seen is significant, a metaphor, and that we only need to know one word: "Icarus."

If we don't get that, he says, "You should probably read more."

Coogan-as-Wilson lets us know when the film is entering its second act, and points out all the cameos in the film by the actual people portrayed elsewhere by actors. Flirting with a beautiful young woman – no less than Miss UK, visiting Granada's studios with Wilson as tour guide – he turns to the audience and chides them for their prurience, insists that it's consensual, and that it's OK because "I'm being postmodern before it was fashionable."

One of the film's recurring characters is a journalist played by Welsh comic Rob Brydon, who aspires (fruitlessly) to harass and demean Wilson. Along with Winterbottom and Coogan, Brydon would become part of an ongoing project even more postmodern than the constant fourth wall breaking in the movie.

Three years after the release of 24 Hour Party People, Winterbottom would make A Cock And Bull Story, a film about an attempt to make a movie version of Laurence Sterne's picaresque 18th century novel, The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman. Coogan and Brydon play fictional versions of themselves, hired to play the roles of Shandy and Uncle Toby respectively.

The Sterne novel is famously digressive – postmodern before it was fashionable, really – and the movie is basically about it being unfilmable, even without Coogan's rampant insecurities and the constant competition between himself and Brydon about who's really the hero of the story.

This in turn spawned a quartet of films: The Trip (2011), The Trip to Italy (2014), The Trip to Spain (2017) and The Trip to Greece (2019), all put together from multi-episode BBC miniseries of the same names, and featuring Coogan and Brydon reprising their fictional alter egos.

The two men – family and personal circumstances changed slightly with each film – bicker and compete constantly while traveling together to write a celebrity travel feature for a British broadsheet. Over exquisite meals and in picturesque locations, they argue about historical trivia, spar over their physical fitness, and engage in an ongoing competition with their impressions of celebrities like Michael Caine, Mick Jagger, Marlon Brando, David Bowie and Anthony Hopkins.

Winterbottom – with what one presumes is Coogan's full collaboration – depicts the actor as neurotic and prickly, whose success in Hollywood (Coogan is known to US audiences mostly for his roles in Tropic Thunder and the Night at the Museum franchise) is contrasted with Brydon's more local fame on TV in Britain and his more consistently happy family life.

Mostly, though, Coogan-as-Coogan in Winterbottom's films plays on the actor's own public image in the UK as an outspoken, opinionated and self-regarding media celebrity who's respected more than he's liked. (In the first Trip film, Coogan has a nightmare that a tabloid newspaper runs a front page headline where he's called a "c*nt." By his own father. This actually segued into a musical number that was deleted from the film.)

All of this begins with Alan Partridge, the character Coogan created thirty years ago – an insufferable TV and radio presenter from Norfolk with his trademark ABBA-derived catchphrase "A-HA!!", whose overbearing personality and fragile ego constantly sabotages his career. Since he debuted on a BBC radio comedy program, speculation has been rife over who Coogan used to fill the irritating empty suit that is Partridge – everyone from chat show host Richard Madeley to DJ Tony Blackburn to culture show presenter Andrew Graham-Dixon.

Coogan has apparently admitted that Partridge – a comic creation so popular that there's a statue of him outside the Norwich Forum – is actually based on Antiques Roadshow host Michael Aspel, though separately he said that Tony Wilson himself provided inspiration, going all the way back to the young Coogan watching him preening through the stairs when he attended parties at his parent's house in Middleton, a Manchester suburb.

The braided layers of acidic satire, collegial contempt and ill-concealed self-loathing involved in this whole equation shouldn't surprise anyone more than slightly familiar with contemporary British comedy and media. Growing up with the almost fetishistic blandness of Canadian media – a reasonable facsimile of good manners veneering a pitiless tall poppy syndrome – it frankly fills me with envy.

But Coogan's Wilson is still treated with obvious affection in Winterbottom's film; Coogan wouldn't approach a character with this much fondness again until his portrayal of the aging Stan Laurel in Stan & Ollie (2018). Coogan-as-Wilson might be a narcissist, but he understands too well that he's just a small part of the musical scene he's created within and for the city that he loves.

"That is my tragic flaw," he tells us in a voiceover as the camera flies over Manchester at night. "My excess of civic pride."

He's a footnote to Curtis and Joy Division, New Order, Ryder, Happy Mondays, Acid House, the Hacienda and one of the last musical movements that could only be experienced in person before social media and the digital tsunami.

"I am," says Coogan-as-Wilson, "a minor character in my own story."

The wheel rolls downward and the film ends with the closing of the Hacienda, the bankruptcy of Factory Records, and Coogan's weed-inspired vision of God over Manchester, assuring him that he was right, that his only mistake was not signing The Smiths, and that Simply Red really were rubbish.

It's a lighthearted moment, bittersweet but final – as anyone who's experienced the end of a cherished youthful scene, musical or otherwise, will attest. Compare the madcap tone of Winterbottom's film with Control (2007), photographer and director Anton Corbijn's dour, tragic biopic of Ian Curtis, which Wilson co-produced. 24 Hour Party People is so irreverent that it makes Curtis' suicide almost cartoonish, whereas Corbijn portrays it with the operatic grief most people would consider suitable.

And if you've ever lived through a scene, or a historical moment that passed with the turning of Boethius' wheel, you'll know that truth and myth are forged together thanks to unreliable memory. 24 Hour Party People begins with this fact, amplified by the participation of the one man who could have untangled fantasy from reality but – knowing that myth will serve him better – can't be bothered.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.