When trying to understand the apparent loss of faith in the American Dream that's been alternately mourned or celebrated by movies for decades now, you find yourself pondering the dilemma of the chicken and the egg. In other words, has the malaise that's overwhelmed not just America but the West in general been inevitable – the result of brute economic, demographic and political realities – or has it been cheered on and accelerated by a morbid culture obsessed with self-harm, like a middle-class teenager secretly addicted to cutting?

And here you are, probably thinking you were just going to read about some old movie.

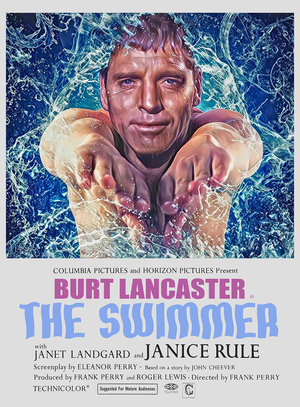

When Burt Lancaster emerges from the woods at the beginning of the 1968 film The Swimmer, clad only in tight blue swim trunks, it doesn't take more than a few moments to realize that this isn't just the story of a man. But what a man: Lancaster's Neddy Merrill is the picture of virility as he launches himself into a swimming pool on the edge of the woods, his broad shoulders pulling him effortlessly from the water after being handed a drink by some unseen hand behind the camera.

His friends – the owners of the pool and another couple joining them for the afternoon – marvel at Ned's physique and energy, the women most openly appreciative. One of the men, an old childhood friend of Ned's, looks at least a decade older. This was Lancaster's specialty – the former acrobat had been playing manly men since his debut in The Killers in 1946, on through roles like Jim Thorpe, Wyatt Earp, Elmer Gantry and Sgt. Milton Warden in From Here to Eternity. He might have complained privately that staying in shape was wearying with the years, but his Prince Fabrizio in Luchino Visconti's The Leopard just a few years earlier made it clear that middle age (Lancaster was in his early '50s when he filmed The Swimmer) was not going to dim his onscreen masculinity.

We're in that earthly Valhalla of postwar prosperity – suburban Connecticut on a summer Sunday, and all the adults are hung over. Neddy the alpha surveys the bucolic countryside around him, realizes he can swim all the way home through his neighbours' pools, and names this river after Lucinda, his wife, who's supposed to be waiting at home with his daughters by their tennis court.

"This is the day Ned Merrill swims across the county," he proclaims to everyone and no one, before bounding off into the trees after one last vigorous lap.

The Swimmer was based on a short story by John Cheever, which was published in the New Yorker in July of 1964. Cheever was once a major American writer, but like so many of his peers (John Updike, Richard Yates, William Styron, Raymond Carver) in our post-literate world, he's been on the road to obscurity since his death in 1982. There was once a misconception that Cheever described the WASP establishment that was ascendant in American society, but his real milieu – as made plain in the movie – is the suburban middle class that evolved from the petit bourgeoisie – scornfully portrayed in the '20s by Sinclair Lewis in novels like Babbit – into real economic majesty after World War Two.

It was a class that aped the style and manners of the Anglo-Saxon Protestant ruling class as their income and affluence increased and they began colonizing the schools and northeastern neighbourhoods where the WASP had built their estates, compounds and summer homes – places like Cheever's fictional community of Bullet Park, where Ned's family waits for him. It was the same class satirized and celebrated in 1980 by the humorous reference book/catalogue The Official Preppy Handbook, a ubiquitous bestseller that helped set the tone for the decade that followed.

According to the definitive five part documentary about the making of The Swimmer produced for a deluxe two-disc blu-ray reissue in 2014 – a bonus feature longer than the film itself – it seems it was Lancaster who wanted to make a film out of Cheever's story, handing the story to his 14-year-old daughter to get her take. Lancaster had taken an active hand in production as the studio system fell apart through the '50s, and he would bring the story to producer Sam Spiegel, riding high on a string of successes like The African Queen, On The Waterfront, Bridge on the River Kwai and Lawrence of Arabia. Directing and scriptwriting was given to the husband and wife team of Frank and Eleanor Perry, whose reputation was built on the psychological dramas David and Lisa (1962) and Ladybug Ladybug (1963).

It would not turn out to be a dream team.

Filmed in the summer of 1966 around Frank Perry's hometown of Westport, Connecticut, the movie elaborated on Cheever's story, giving Ned a profession (ad man) and reducing his family from four daughters to two, but retaining characters like the Hallorans – wealthy and socially influential nudists whose eccentric lifestyle, in Eleanor Perry's script, has alienated their more conservative daughter. Cheever's description of the couple is weirdly evocative:

"The Hallorans, for reasons that had never been explained to him, did not wear bathing suits. No explanations were in order, really. Their nakedness was a detail in their uncompromising zeal for reform and he stepped politely out of his trunks before he went through the opening in their hedge."

Young people are well outside the purview of the adult world in Cheever's story, but the Perrys inserted the younger generation firmly into their script. There's the forlorn little boy Ned finds selling lemonade by the gates at the bottom of the drive of his family's estate; his parents have separated, are summering separately and have left the boy alone in the care of servants with – as Ned discovers to his dismay – a drained swimming pool.

The care and compassion with which Ned treats the boy – teaching him to swim across the empty pool, offering emotional solace that seems to come from a similarly lonely, neglected place in his own past – does much to make Lancaster's Ned sympathetic, despite our growing suspicion that there's something deeply off about the man, especially when he's offering well-intentioned advice.

"You're the captain of your soul," Ned tells the boy. "That's what counts, you know what I mean?"

"These kids of mine think I've got all the answers," he boasts as they swim through the bright air at the bottom of the pool. "These kids of mine think I'm just about it."

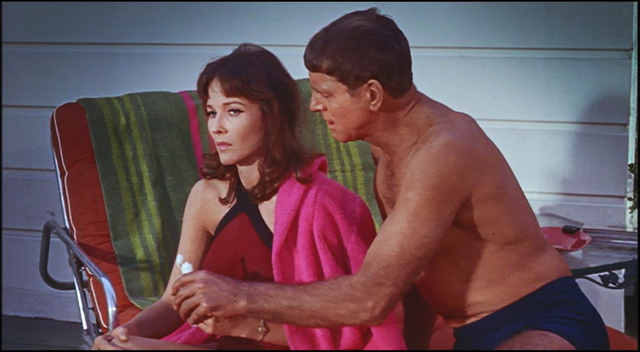

The generation gap pulls even wider when Ned encounters Julie, his daughters' old babysitter, in another pool along his way. Played by California girl Janet Landgard, Julie is impossibly fresh, pretty and blonde, and she impulsively joins him on his pool portage. Walking through the woods while the camera work turns into a dreamy reverie, she admits that she once had a crush on Ned, stealing one of his shirts from his closet and imagining herself older and more worldly, meeting him again in Paris. Ned responds with inappropriate enthusiasm, offering to become her chaperone in the city, protecting her from unwanted sexual advances; his avid plan to become her white knight and protector scares the girl, and she flees from him back through the trees.

Much of the dreamlike sequence with Ned and Julie was filmed later, by Lancaster's friend Sydney Pollack, in California, after co-producers Sam Spiegel and Roger Lewis had taken the film away from the Perrys for editing and re-shoots. After promising Lancaster that he'd be available during filming, Spiegel had spent the summer on his yacht in Europe, leaving the star and the directors to deal with "bad cop" Lewis, who spent most of his time on set shirtless and enjoying the various pools they'd rented as locations.

Spiegel also tried to turn his star and the Perrys against each other, telling the couple not to show Lancaster any daily rushes, while telling Lancaster that Frank Perry's insecurities as a director were why Lancaster was barred from seeing any footage. Several scenes were recast and reshot by Pollack; a sequence with Billy Dee Williams as the Hallorans' chauffeur – a scene that sharply hints at a history of casual racism beneath Ned's affable manners – was apparently lost, as was a key scene near the end, where Ned ends up by the pool owned by Shirley, his former mistress, originally played by actress Barbara Loden, whose husband Elia Kazan apparently pressured Spiegel to cut his wife's scene.

Reshot by Pollack in California with Janice Rule as Shirley, the scene comes after he crashes a raucous party given by the Biswangers, who treat their guests to caviar and crackers under the massive new retractable dome over their pool. They're new money, and Cheever made it plain what someone like Ned thought about them in his story:

"The Biswangers invited him and Lucinda for dinner four times a year, six weeks in advance. They were always rebuffed and yet they continued to send out their invitations, unwilling to comprehend the rigid and undemocratic realities of their society. They were the sort of people who discussed the price of things at cocktails, exchanged market tips during dinner, and after dinner told dirty stories to mixed company. They did not belong to Neddy's set – they were not even on Lucinda's Christmas card list."

He meets another woman – a trashy bouffant blonde in pink and white played by the late comedienne Joan Rivers in her first acting role. He tries to convince her to take Julie's place with him on his journey through the swimming pools, but his vitality and machismo has by now curdled into narcissism.

"I'm a very special human being," Ned declares when she treats him like just another horny man on the make. "Noble and splendid."

The Perrys give Ned lines like this all through the film, and by now we're sure that Ned's perfect life is a fantasy.

Janice Rule's Shirley is an actress who carried on an affair with Ned in hotels and during out-of-town runs of plays. This sort of sexy, mature woman was Rule's specialty, and you can see why Ned the narcissist felt entitled to enjoy her. She has to remind him of how he ended their affair – Ned's grasp of time and truth is increasingly unreliable with every encounter - and while she still has feelings for Ned, his rough, desperate neediness turns violent. She has to double down on the cruelty in her return salvo of a rejection, dismissing him as a "suburban stud" but that, even then, the sex had never been that good anyway. The insult doesn't come out of nowhere; earlier in the film, in a scene apparently inserted during Pollack's re-shoots, we'd seen Lancaster's Ned actually race a very eager stallion.

Shirley's angry tirade is a grievous wound, and Ned crumples in agony, shuffling out of her pool like a deflated Rodin sculpture.

Ned's final humiliation is at a crowded public pool, where he's forced to shower and endure inspection of his extremities, gag on the over-chlorinated water, and confront a hostile group of local shopkeepers who accuse him of stiffing them on bills. He flees from them into the woods and finally makes it home as the skies open – a classic Hollywood storm, sheets of rain pouring down from a sunny sky.

The gardens are overgrown, the tennis courts are a wreck, and the house is locked up and empty. While Lancaster's Neddy beats on the door, moaning and wailing like a wounded animal, the camera tracks through a broken window into the darkened mansion, tennis rackets piled against a box in the middle of the dusty floor, under a chandelier with an auction tag hanging from its crystal pendants.

The film was not a success when it was released in 1968, but its narrative ideology and influence would be lasting. The 90-minute story, a mix of Narcissus and Odysseus set to a backdrop of class anxiety and cultural decline, is basically the same one that would take place over seven seasons of Mad Men; if you knew your Cheever, it was easy to imagine Ned sharing the commuter train into Manhattan with Don Draper. When the AMC series began, it even had Don and his family living in Ossining, NY, the same bedroom community Cheever called home when he died.

I was born the same week Cheever's original story was published in the New Yorker, seven months after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, a Catholic whose family had excelled in their imitation of high WASP style. Ten years or so later, a teacher at my Catholic grade school would screen a very expurgated 16mm print of the film to us during English class. I remember finding it baffling, even scary; if this was what being an adult involved, I was in no hurry to grow up.

The world of The Swimmer was recognizable to me years later, when Ang Lee made a movie out of Rick Moody's 1994 novel The Ice Storm, set in a Connecticut commuter suburb less than a decade after The Swimmer. It told a similar story from a very Generation X perspective – the unsupervised kids growing up with Watergate and stagflation, their parents active soldiers on the front lines of the sexual revolution, hooking up and coming apart.

When we talk about the youthquake that unsettled and remade Hollywood in the late '60s, Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider gets cited inevitably. But in hindsight it's difficult to see that the story of Wyatt and Billy crossing America on their motorcycles was more influential than a flop like The Swimmer, made by a movie star, a post-studio mogul and a pair of middle class bohemians that helped fix the image and pass judgment on a whole social class that, just a decade earlier, was certain that it had taken the commanding heights of society. If, like Ned, their fortunes were declining, it was because they had revealed themselves as morally unworthy; the only questions that remains unanswered are when society made that judgment, and how they became convinced of their own guilt. It's certain that a film like The Swimmer helped.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below, as access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club.