I mentioned in my last piece that the standard (mis)interpretation of Oedipus Rex—that Oedipus got what he deserved thanks to a moral shortcoming he couldn't or wouldn't correct—traces back to an earlier misinterpretation of Aristotle's comments on tragedy. That provides a nice segue, because what Aristotle actually says in his Poetics (and his Politics) provides further insight into our current problems.

What Aristotle actually points out in Chapter 13 of Poetics is that great tragedies revolve around hamartia (ἁμαρτία) inherent in, or committed by, a protagonist. All this Greek word refers to is error. It does not necessarily imply moral shortcoming (although the word can cover that, too; New Testament writers used it in just this way). Hamartia, unless specifically used in a moral context, simply points to human frailty or limitation. As such, it covers even the most innocent of mistakes—like those resulting in an unavoidable (Oedipus-style) lack of omniscience. As the Scottish poet Robert Burns would write 2000 year later, even "the best laid plans o' mice an' men gang aft agley". Hamartia is the reason. Both Biblical and Greek thinkers agree.

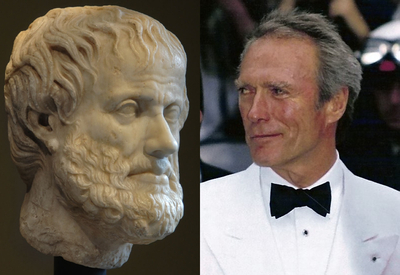

So, back to Aristotle. He is an early and strong endorser of the Eastwood Rule about knowing our limitations. In fact, in his Politics, Aristotle completes one of the classic "flames" of all time: he, in effect, lights up his own real-life teacher, Plato, for endorsing the limitation-denying Utopian fantasies of Socrates, Plato's teacher and hero.

You might recall that in The Republic (written by Plato himself), Socrates reasoned that true justice would require state-enforced, radically egalitarian, totalitarian communism—at least among a permanent ruling class, but ideally among everyone. The 20th century political philosopher Leo Strauss would later claim that Socrates's comments amounted to a reductio ad absurdum. His real intention, argued Strauss, was to highlight the great costs to any society of trying to realize perfect justice (as one could rationally fathom perfect justice). Thus, on Strauss's account, Socrates was actually an anti-Utopian, as was Plato, by extension.

Maybe Strauss's view is correct. But Aristotle doesn't think so. He spends chapters II and III of Politics incinerating Socrates's arguments. He clearly believes they were made in earnest. (And you'd think Aristotle would know, given that he spent two decades studying under Plato at the Academy in Athens).

In any case, for Aristotle, the proper place to start ratiocination about human life—including politics—is through the honest observation of human beings as flesh-and-blood members of the animal kingdom. What such observation reveals, he says, is a particular nature which inclines human beings toward particular behaviors, dispositions, aspirations, etc., and away from others. Nature itself puts limits on what we can expect from human beings.

This is why Aristotle rejects Socrates's Utopian totalitarian communism: it is incompatible with human nature. Among other things, it demands the abolition of private property. It demands the abolition of the family unit and replaces it with commonality of women and children. It demands the narrowest restrictions on every aspect of life in service to the state. And by equating equal with identical, it denies—it makes war upon—the natural variation of individuals within the boundaries of human nature, and without which no human community can thrive (or even survive).

In short, Socrates's allegedly just republic will make people miserable, create chaos, and ruin any polis which embraces it. It is worse than a mere non-starter. It is something profoundly anti-human. And the trouble all begins, according to Aristotle, with Socrates imagining human beings to be something they aren't, and can never be. Aristotle stops short of describing the prescriptions of his teacher, and his teacher's teacher, as lunatic—but in my reading, that word hovers just beneath the surface of every line of his critique.

In addition to the demolition job on Socrates and Plato, what we get in Aristotle's Politics is a fairly dense exploration of political life. That I know of, it's the first serious work of political science in history. In it, he compares and contrasts various constitutions and forms of government. He considers the meaning and proper role of citizenship. He considers how population size, demography, and even climate might affect politics. He looks at the function of the arts. He examines the role of the family, and other forms of association, within a polis (which itself is a form of association). He considers property rights, the dangers of faction, city planning, and dozens of other things. I can't say Politics is an easy read, but I can say there's a lot of valuable, thought-provoking material there.

But in the space remaining, I want to just preview two key claims from Aristotle directly relevant to our discussion here. (I'll preview a couple more next time.)

The first is that the only sensible starting point for trying to understand anything at all about the world is to assume that purpose is sewn into nature.

For Aristotle, this is no irrational assumption. Rather, he believes everything in nature evinces purpose in possessing a certain essence—some intrinsic, fixed set of qualities—which indicates the particular end inhering in that object. The word Aristotle used to describe this end is τέλος, or telos. So, he writes in Physics, the telos of an acorn is to become an oak tree. Where the right external conditions are in place (nutrient-rich soil, water, sunlight), the acorn achieves full fruition as an oak tree. Ideally, it becomes the finest oak tree it could ever become.

Human beings are the same, says Aristotle. We embody a telos just like an acorn: an end-state of thriving and completion. And we also need the presence of certain external things to achieve it. Nature points to an end or purpose, but we also need the right kind of nurture to get us there.

So what is our telos? It is to live a life of εὐδαιμονία, or eudaimonia, he says. This word is often translated as "happiness", but this doesn't really do the word justice. What living a life of eudaimonia amounts to, for Aristotle, is living a life of flourishing and excellence, virtue and reason, blessedness and adequate means, contentment and "good-spiritedness" (the literal meaning of the word). It's a kind of expanded version of what we think of, when we think of "the good life".

The second claim is that human beings are social by nature. They want and need to belong. They wilt in isolation. They can only thrive—achieve their telos—within what Aristotle calls a κοινωνία, or koinónia, and indeed, overlapping koinonias. This word is usually translated as community, association, partnership, or fellowship. It describes a group of people who share in something—most fundamentally, who share some common purpose.

For Aristotle, there is no pre-social state in human history. Go as far back as you can, and you will always find human beings living in groups (starting with the family), embedded in various webs of social relationship. What underlies that rich social layering is "natural impulse", he says—that is, instinct. Males and females mature, then pair-bond; they create children and start a family; that family joins with other already-joined families in a village; the children grow up and start their own families, which in turn join with other families; and at some point, that community of families amounts to a proper, formal city-state or nation-state. At every point, forms of hierarchy exist, and always must exist; there can be no social group without some form of leadership. So do overlapping forms of (usually inherited) obligation and identity. But again, his key point here is that while human beings make choices along the way, the unfolding and realization of human sociability is driven mostly by nature or instinct (not, say, by detached, rational calculation of self-interest).

In short, says Aristotle, man is by nature zoon politikon—a political and social animal constrained by nature to thrive as a member of a led community, and in truth, many overlapping forms of community, relationship, obligation, and belonging.

(More on Aristotle's teleology, anthropology, and political insights—and why they matter—next week.)

Tal will be back here next week to continue the conversation. Mark Steyn Club members can weigh in on this column in the comment section below, one of many perks of club membership, which you can check out here.