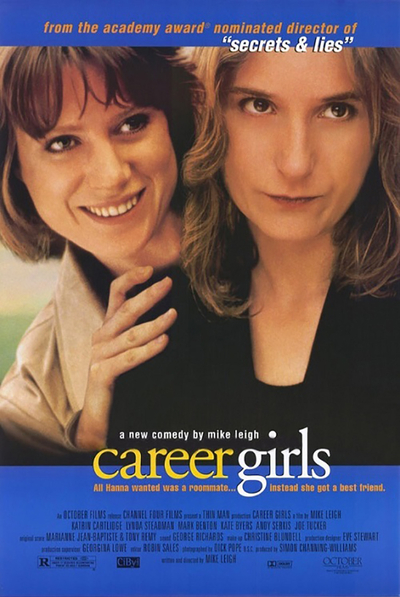

Career Girls is an unusual film if only because it starts with a happy ending. Director Mike Leigh's early work was full of films about British working class life, some grimly humorous (Life Is Sweet), some simply grim (Naked). Released in 1997, Career Girls was the first film where Leigh let himself be really gentle with his characters, using a story told with flashbacks to allow them the provisional gift of time and maturity.

We meet Annie (Lynda Steadman) on a train to London, where she's spending a weekend with her old college roommate Hannah (Katrin Cartlidge). The two haven't seen each other since they graduated six years previous; the reunion is awkward, but it's nowhere near as uncomfortable as their early days sharing student digs in Camden Town, at first with a roommate who they discard after a bond forms around shared childhood misery.

Present day Annie and Hannah look confident and put-together, newly thirtysomething and unmarried; the urban archetype implied by the film's title. Hannah's top-floor Kentish Town flat is bright, clean and unremarkable – a well-lit place to prepare for the next step in life, whatever that might be. They gingerly reacquaint themselves over salad and wine. They talk about real estate; Hannah is looking for a place to buy, and suggests that Annie come along for a laugh instead of pretending to be a tourist.

A decade earlier Annie was an anxious mess. An asymmetrical hairdo dyed chemical orange does nothing to distract from scabby skin and a tragic case of dermatitis; she's unable to meet anyone's gaze, looking at her feet or rolling her eyes toward the ceiling. Her breathy voice with its Yorkshire accent quivers nervously, and she's never far from tears. A decade later, her onetime roommate is comfortable describing her as "a walking open wound."

Cartlidge's Hannah is her polar opposite, tactless and hostile to everyone. She's a mass of off-putting tics, slapping her forehead and twisting her fingers into a beaklike mouth, which she thrusts at people to emphasize every mocking verbal thrust. She's clever but charmless, riffing and punning incessantly to hold the high ground in conversation:

"It's not brown, it's maroon – we're marooned."

"I've got a funereal disease."

Together Annie and Hannah make for nearly unendurable company; it's no wonder they find solace in each other. An adult would recoil from this much spiky, neurotic energy, but one of the gifts of youth is ignorance of appropriate behavior; until we learn about context and decorum, we're remarkably tolerant of our peers acting out, while holding grown-ups to a higher standard that's inexpressible (and not-so-secretly resented.)

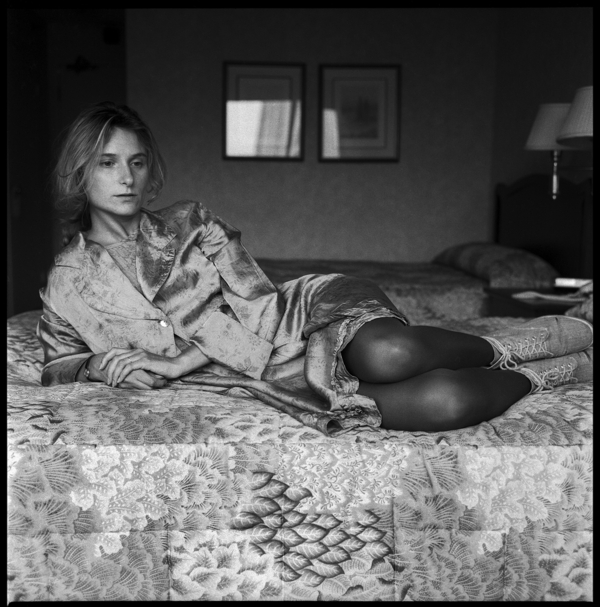

Mike Leigh, 1996 (Credit: Rick McGinnis) |

Mike Leigh is famous for long rehearsals he holds with his actors, without more than the barest outline of a script. Workshopping characters as they build them from almost nothing, they help Leigh create plot and dialogue and fully inhabit their roles when filming finally begins. On paper his early films read like textbook British kitchen sink realism, but the effect is highly stylized; nobody who knows and loves Leigh's films would use the word "realistic" to describe characters like Jane Horrocks' Nicole or Alison Steadman's Wendy (Life is Sweet), David Thewlis' Johnny (Naked), Brenda Blethyn's Cynthia (Secrets & Lies) or Sally Hawkins' Poppy (Happy-Go-Lucky). Like the student-aged Annie and Hannah, they're outsized and indelible, even strident.

In Career Girls the contrast between the adult Annie and Hannah and their younger selves is vivid. At first we suspect their student personas are exaggerated by memory, the way remembering and retelling our past demands editing and dramatizing to create stories that are worth the effort. This is enhanced by Leigh treating flashback scenes like a period film – the post-punk and Goth '80s, with The Cure on the soundtrack and the Smiths t-shirt on the undergrad lothario the girls end up sharing.

One of the best bits of business created by Leigh, Steadman and Cartlidge is the "Ms Bronte" game. Using their dog-eared paperback of Wuthering Heights (either the Oxford Classic or Penguin editions familiar to any student in the '80s) they summon the spirit of the spinster author like a Ouija board, picking random passages from the book to tell them if sex or romance is in the offing.

Like the realistically cramped and dingy flat above a Chinese takeaway the young women share – I remember dozens of similar spaces, right down to the cast-off furniture one move away from curbside oblivion, stale cigarette smoke, cooking odours and cheap incense – it brings back that stage of life with a start, evoking the gags and rituals you create when the future needs to be held at bay by treating it like a game of chance or a joke.

But their younger selves reemerge during their weekend together, when they reminisce or encounter people from their past – their old roommate jogging up Primrose Hill, the former lothario now an estate agent showing Hannah a flat. Anxious, surprised and shocked, Annie tugs at her hair and swivels her head and Hannah's old belligerence returns. The past, and their far unhappier selves, are still just under the skin, and we realize why Annie might have found excuses to postpone her reunion with Hannah.

The women unwittingly spend the weekend playing chicken with their memories, the most poignant of all embodied by Ricky – a stunning performance by Mark Benton. Ricky – overweight and slovenly, an awkward mess of twitches, winces and squints with a Geordie stutter – is probably the only classmate who makes Annie and Hannah seem socially palatable. They let him bunk on their sofa when his landlord kicks him out and adopt him as their mascot.

The evening where they draw Ricky out of his shell and get him to dance with them in their living room (to The Cure's "The Walk") is a joyous moment of near-abandon, obviously the closest thing to happy Ricky's been in a long time. He has feelings for Annie, however, which aren't reciprocated. Rejected, Ricky disappears from the flat and school, and the girls travel to Hartlepool to see if he's alright, but it ends, inevitably, badly.

The weekend of coincidences culminates when they take a sentimental journey to their old flat on the way to King's Cross Station and Annie's train home to Wakefield. The takeaway downstairs is boarded up, and Ricky sits dejected on the front stoop holding a giant stuffed elephant toy – a gift for the infant son that the boy's mother won't let him visit.

It's clear by now that Ricky's painful awkwardness was a harbinger of deeper mental illness; he's only semi-coherent, but remembers Annie and Hannah well enough to remain angry with them for the nearly decade-old rejection. Ricky's state upsets the women terribly, mostly because they're ill-prepared to help him, and perhaps partially because they realize that meeting them might ultimately have tipped his life into tragedy.

I once came across a college friend, several years after graduation, living in his car and beset with paranoid fantasies. A group of his old classmates tried to help him, but our sense of helplessness and guilt was terrible, underlined by the knowledge that we'd survived the gauntlet of youth and early adulthood much more cleanly than he had.

It's tempting to call Career Girls a deferred coming of age film. After the youthquake of the '60s the transition to adulthood migrated upwards into one's twenties; Hannah and Annie are Generation X, the last generation of unsupervised children, and the first to experience downward mobility, the slow erosion of living standards and opportunities their parents and older siblings took for granted. It takes the friends time and effort to find a mature place in their lives, but they find it just in the nick of time.

It's also one of the first films I recall that took for granted a palpable and growing sourness between the sexes. All of the men Annie and Hannah encounter over their weekend reunion – the laddish futures trader showing off his Canary Wharf flat (Andy Serkis), the college-lothario-turned-estate-agent, and even Ricky – inquire with prurient interest if they're a couple, or angrily call them lesbians.

The friends assume that finding a suitable man now that they've crossed into their thirties is mostly a matter of luck, though they admit that their own lingering issues with absent fathers and dependent mothers might also be a problem. I'd watched this gulf grow between men and women since my teens, but it was startling to see it described on film when I saw Career Girls in the theatre, nearly a quarter century ago. As far as I can tell things are much worse today.

Katrin Cartlidge, 1996 (Credit: Rick McGinnis) |

Steadman and Cartlidge are onscreen, together or apart, for the whole film, and its success rests on how convincingly they sell Annie and Hannah's friendship over ten crucial years in their lives. Saying goodbye at the train station, Hannah gives Annie a gift – her old paperback copy of Wuthering Heights. Hannah insists that Annie play the old game; she asks "Will I find true happiness soon?"

Hannah consults the book. "'Pang,'" she reads out. "Load of rubbish, always was."

After Career Girls Mike Leigh took an unpredictable turn and he began making period films, like Topsy-Turvy (1999), a biopic about operetta legends Gilbert and Sullivan, Mr. Turner (2014), another biopic about British landscape painter J.M.W. Turner, and Peterloo (2018) a film about the infamous 1819 massacre of marchers demanding political reform and voting rights by government militia outside Manchester.

Lynda Steadman's work was mostly on television, and seems to have ceased onscreen in the early 2000s. Katrin Cartlidge died suddenly in 2002, just 41 years old, and on the verge of what were anticipated as the best years of her career. Someone watching Career Girls for the first time today would meet Annie and Hannah like strangers, unacquainted with the actresses playing them. As the credits roll, it's hard not to hope that Annie and Hannah's ad hoc happy ending might linger, strengthened by the weekend's renewal of their friendship, authors of their own modest happiness, finally free and clear of Ms Bronte and indifferent chance.