The Look Of Love

Is in your eyes

The look your smile can't disguise

The Look Of Love

Is saying so much more...

A couple of decades back, "The Look of Love" was indeed saying so much more: George Will cited the presence on the hit parade of Diana Krall's CD of the same name as one of the hopeful cultural trends of America post-9/11. In The Wall Street Journal, Terry Teachout agreed. He'd been sitting in a New York McDonald's whose radio had been tuned to some young persons' station - and, instead of the usual ghastly caterwauling, "The Look of Love" had drifted over the McMuffins and hash browns:

"Is Diana Krall's current popularity a fluke?" mused Mr Teachout. "I've been thinking that it might have a little something to do with September 11th... Unless I miss my guess, beauty is becoming fashionable again."

It's safe to say he missed his guess. Nineteen years on, the Top 40 is more vulgar, more witless, more pneumatic than ever - and a return to standards, either in the George Will or George Gershwin sense, is further off than ever.

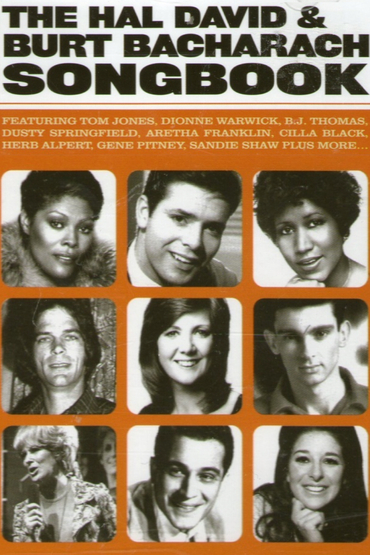

Nevertheless, the song endures, as do many others by a man who was born one hundred years ago, May 25th 1921. As you can calculate from that date, Hal David belongs to the pre-rock generation. Yet he had his greatest run of success in the 1960s, when the likes of "The Look of Love" and "I Say a Little Prayer" and "Make It Easy on Yourself" were competing on the charts with Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones and sundry lesser rockers. Hal was one half of "Bacharach & David", one of the most famous songwriting teams in the world back then, if only because the very notion of a songwriting team - Lerner & Loewe, Rodgers & Hammerstein - seemed quaint and cobwebbed.

But in the age of the "singer-songwriter" Bacharach & David were household names. Burt Bacharach, the music guy, was the really famous one - a conductor-pianist, a celebrity and a star, the embodiment of what they called in Britain, somewhat to his bewilderment, "the Bacharach sound". "I think it was something to do with the flugelhorns," he once told me. Women, in particular, grew very flugelhorny in his presence. He was a bona fide sex symbol. "Every songwriter looks like a dentist," said Sammy Cahn, "except Burt Bacharach."

Hal David made a passable dentist, and thus generated fewer magazine covers and gossip columns, content for the most part to be the other fellow to Burt's Bacharach. The general assumption was that Burt was the great artist, Hal the solid craftsman who did a good professional job. Some scholars go further than that. In his tome The American Songbook, Ken Bloom writes:

There are three kinds of songs: those in which the music and lyric are equal in importance (think Gershwin), those in which the lyric is more important than the music (think Sylvia Fine), and those in which the music far overshadows the lyrics (think Bacharach and David).

Crikey. As we've noted before, Ira Gershwin is a very problematic lyricist: No one could seriously argue that the lyric of "I've Got a Crush on You, Sweetie Pie" or "The Man I Love" ("Someday he'll come along... and he'll be big and strong") is the equal of the tune, and I'd contend that that mismatch is already denting the longevity of certain terrific George Gershwin melodies; posterity-wise, he'd be in much better shape if he'd written with, say, Dorothy Fields ("The Way You Look Tonight"). As for the second category, insofar as there are songs in which the lyric is more important than the music, Sylvia Fine's no example thereof. Nobody sang her songs except her husband, Danny Kaye, and even he took the precaution of making them marginally less unfunny by rattling them off at express speed. (I'll make one slight qualification to the preceding: "Lullaby in Ragtime" is not without a modest appeal.)

Which brings us to Bacharach & David. On, say, Gene Pitney's masterpiece "Twenty-Four Hours from Tulsa" (1963), I love Bacharach's psycho mariachi trumpets. But that's an orchestrational ornamentation. The song is driven by David's narrative:

Dearest

Darlin'

I had to write to say that I won't be home anymore

'Cause something happened

To me

While I was drivin' home and I'm not the same anymore...

It's harder than it sounds. You take Bacharach's notes and try coming up with "as I pulled in outside of the small motel she was there":

David uses Bacharach's staccato pairs of notes to tremendous dramatic effect:

She took me to the café

I asked her if she would stay

She said

'Okay'...

Likewise, "Alfie" (1966), for which David wrote the lyric first and Bacharach then set it. Many authors are minded to muse philosophically - "What's it all about?" - but not many would wish to do so within the constraints of a song bearing a blokey Brit name like "Alfie". David pulled it off so well that it's Bacharach's favorite among his own compositions. He also admires the breezy distillation of an entire ethos in "Do You Know the Way to San José?"

LA is a great big freeway

Put a hundred down and buy a car

In a week, maybe two, they'll make you a star

Weeks turn into years

How quick they pass

And all the stars

That never were

Are parking cars

And pumping gas

[pump-pump-pump]

That's wonderfully written. The Gershwin comparison is relevant only in the sense that, temperamentally, Hal David was content to play Ira to Bacharach's George. Like George Gershwin, Burt squired glamorous women of the era (Angie Dickinson). Like Ira, Hal rarely got mentioned by celebrity magazines except in paragraph 47 of profiles of his composing partner. But, on the big Bacharach numbers, David more than did his share. In fact, he made Bacharach sing easier. The tunes were certainly more interesting than the average rock number, in both their harmonies and their shifts of time-signatures (the 3/4 bar in "I Say a Little Prayer", for example), but they never sounded tricksy because Hal David's words made them sing so effortlessly. "I marvel at Hal's selflessness," Elvis Costello said to me after his own collaboration with Bacharach. "He always served the music."

David liked simplicity. "Most of us, when we start to write, try to be clever," he told me many years ago. "It takes us a long time to find the confidence to express things simply. But to me the perfect song is one which sounds as if the singer's just making it up as he goes along; it unfolds naturally." The example he quoted that day was Irving Berlin:

What'll I Do

With just a photograph

To tell my troubles to?

He described the Berlin waltzes of the early Twenties as "the quintessential popular songs". In 1987, while his wife Anne was dying of cancer, Hal chanced to hear Liza Minnelli and Michael Feinstein's medley of Berlin's "Always", "Remember" and "What'll I Do". "At a very difficult time of my life," he said to me, "that recording meant so much more to me than anything else around. In three minutes, a song can touch a chord and, ever after, define certain moments for you - more than books, plays or any of the supposedly more difficult forms."

As a young man in Brooklyn, he didn't know Irving Berlin but he knew a lot of other writers. His older brother Mack was a professional lyricist, and young Hal met some of the other local fellows who'd broken into Tin Pan Alley, such as Jack Lawrence and Arthur Altman, writers of our Song of the Week #122 "All or Nothing at All". Mack David's catalogue includes the English lyric to "La Vie en Rose", and a big Johnny Mercer hit "Candy", and Duke Ellington's "I'm Just a Lucky So-and-So" - oh, and "This Is It", Bugs and Daffy and Porky and the gang's big "on-with-the-show" theme for The Bugs Bunny Show. Brother Mack also wrote "Sunflower", a country-ish number that was a modest hit for Frank Sinatra and made a ton more money after an out-of-court settlement in a plagiarism suit over the marked similarities between "Sunflower" and the later song "Hello, Dolly!" As that ragbag of credits suggests, it's not easy being a jobbing lyric-writer with no regular composing partner. Mack David advised his younger brother to go into journalism instead.

For a while, Hal did. But songs were what he wanted to write, and in the years before he met Bacharach he had a few hits: "Broken Hearted Melody", for Sarah Vaughan, is still played; "The Four Winds and the Seven Seas", for Vic Damone, not so much. My favorite David song from this period was written with the aforementioned Arthur Altman and Redd Evans, a floral novelty Sinatra had a hit with in 1950:

Daisy is darling

Iris is sweet

Lily is lovely

Blossom's a treat

Of all the sweethearts

I've yet to meet

Still I finally chose

An American Beauty Rose...

I had no idea what an "American Beauty Rose" was when I first heard the song, but I liked the conceit - and Hal certainly kept it going:

Pansy is pretty

Willow is tall

Violet's kisses

Two lips recall...

The best bit is the freewheeling middle section itemizing the various superior features of the American Beauty Rose:

Why she's clingier

Than Ivy

And she's zingier

Than Black-Eyed Susan

Springier

Than Mabel in June

As daffy as a daffodil

It's laughable the way I thrill

When Roses are in bloom...

That false rhyme - "June"/"bloom" - disfigures an otherwise goofily irresistible song. Sinatra liked it enough to record it twice - first in 1950 in a bouncy Norman Leyden arrangement conducted by Mitch Miller; then in 1961 with a freewheeling Heinie Beau chart conducted by Billy May:

And, zingy and daffy as it is, it suits Sinatra rather better than some of the Bacharach & David things he recorded in later years ("Close to You", for example). But then it took Bacharach & David a few years to become Bacharach & David. Their first hits - "The Story of My Life" for Michael Holliday in 1957, "Magic Moments" for Perry Como in 1958 - sound closer to "American Beauty Rose" than to "I Say A Little Prayer" or "A House Is Not a Home".

But in 1962 they asked a jobbing vocalist called Dionne Warwick to come in and sing "Make It Easy on Yourself". She thought she was making a single. In fact, Burt and Hal just needed someone to do a demo they could pass to Jerry Butler, the guy they had in mind to record it. Dionne was not happy when she found out, and yelled at them, "Don't make me over, man!" - ie, "Don't screw me over." Hal liked the phrase, and, modifying its meaning to "Take me as I am", wrote it up for Dionne. "Don't Make Me Over" is, I think, the first Bacharach & David song that sounds as what we think of by that description - that's to say, an harmonically adventurous ballad with a vernacular lyric that approximates to what the Golden Age songwriters might have come up with if they'd shown up thirty years later and rock'n'roll had never happened.

After a while, it became their default style: "Anyone Who Had a Heart", "A House Is Not a Home", "Always Something There to Remind Me", "Walk On By", "I Just Don't Know What To Do With Myself"... During his Austin Powers revival in the Nineties, I was sent a boxed set of Bacharach classics, and I remember really looking forward to sticking it in the CD player and then being kind of disappointed at how samey "the Bacharach sound" was after the first couple of dozen. My favorites from these years are the anomalies - Tom Jones bellowing "What's New, Pussycat? Whoa-o-o-o-o-oah!" or the jazzy little waltz they wrote for the film Wives And Lovers that Hal David told me he thought was "too hip to be a hit". Jack Jones made a terrific record, and, hipness notwithstanding, it turned out a hit. And then people started complaining it was chauvinist. A few years ago, I had a vague idea for an album called Songs for Swingin' Sexists, comprised mostly of tunes from the "Girl Talk" era. Bacharach & David's "Wives And Lovers" would certainly make the cut:

Hey, little girl

Comb your hair

Fix your make-up

Soon he will be at the door

Don't think because

There's a ring

On your finger

You needn't try anymore...

Just to double the fun, here's Jack singing it to an army nurse in Vietnam (with subtly amended lyric):

Elvis Costello told me he thought Hal David's lyric was meant to be "ironic". "Oh, come on," I said. "There's not the slightest evidence he meant it as anything other than for real." But poor old Elvis felt obliged to make an effort to justify his enjoyment of the song. A few hours after he'd advanced his "ironic" argument, I saw him sing it, in a very stripped down arrangement, accompanied by Burt at the piano. He did a grand job, but it still wasn't ironic.

On the other hand, I don't entirely rule out Jack Jones' assent in 1979 to a disco remake being at least somewhat ironic:

When it comes to less controversial boy-meets-girl stuff, David's great strength is strong titles and lyric concepts. He doesn't always advance them as far as he might, but he doesn't need to: "I Just Don't Know What to Do with Myself", "There's Always Something There to Remind Me", "What The World Needs Now Is Love, Sweet Love" - the title's half the song, and it's good enough to carry the rest.

In 1967, Bacharach was scoring a picture called Casino Royale - not the more recent Bond reboot with Daniel Craig, but a 007 all-star spoof (David Niven, Peter Sellers, Woody Allen, Deborah Kerr, etc) that's all but unwatchable today. Bacharach's score doesn't help: It has its moments (the title theme), but the forced, nudging quality of his "funny" music is at odds with anything happening on screen. A few years back, I chanced to be talking with Tim Rice in London about Bacharach and John Barry (house composer for the Bond films), and we discussed certain qualities they had in common. Then I flew back to New Hampshire and caught the last half of the Bacharach Casino Royale, and realized how very grateful I was that no one had asked Burt to score Goldfinger.

At any rate, Bacharach was watching an early cut of the film, and the memorable seduction scene with Ursula Andress. It's not entirely for real - it's with Peter Sellers, after all - but the sofa, the fish tank and Andress eager to undress was enough to inspire the composer to write a smoldering sax theme. That's what it was meant to be: An instrumental. But it was so obviously a vocal line that David was called on to supply a lyric. Hence "The Look of Love".

That's such a great title you wonder why no one had ever come up with it before. In fact, someone had - Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen in a ring-a-ding-dinger for Sinatra five years earlier. In this case, "The Look of Love" is "the look that leaves you real shook" - a quintessential Sammy line:

There's nothing wrong with that "Look of Love": It does its job in the Frank/Nelson Riddle/Cahn & Van Heusen style, even if it does sound as if the boys wrote it in five minutes. But it doesn't quite grasp what a great title it's got. Sammy Cahn conceded to me many years ago, in a rare moment of self-reflection, that Hal David had rung more juice out of the concept. Bacharach & David's version is better than the film deserves, but it's just right for that moment. If you ever found yourself on a sofa with Ursula Andress late at night in a small apartment, this is the song you'd want:

This "Look" is in close-up: Musically and lyrically, it's very intense. And then the controlled observation of the main theme yields to the anticipatory ecstasy of the release:

I can hardly wait to hold you

Feel my arms around you

How long I have waited

Waited just to love you

Now that I have found you

You've got The Look Of Love

It's on your face

A look that time can't erase...

That's Hal David at his best, serving the music superbly. And then it all wanders off a bit:

Be mine tonight

Let this be just the start

Of so many nights like this

Let's take a lover's vow

And then seal it with a kiss...

And that's Hal David on autopilot - trite sentiments ("be mine tonight"), formulaic expressions ("seal it with a kiss"). But it doesn't matter - because the central idea is so strong and so in tune with the music. In my disc-jockey days, I had a mild preference (which I'm not sure I have these days) for Gladys Knight taking it slow and soulful, aside from the occasional interjection from her oddly orgasmic Pips:

It's very hard for a female vocalist to go wrong with this song. To be honest, that's why I was flummoxed by the success of the Diana Krall version. I'm all for distant Hitchcockian cool - I've got a ton of Julie London albums - but Miss Krall sounded awfully detached from the song's sentiments. Pottering around the room about a year after "The Look Of Love" came out, I heard her moaning low from the TV in the corner and thought "Don't tell me they're still plugging this album," but no: "The Look of Love" had moved seamlessly on from selling CDs to selling the new Honda Lethargo or Toyota Catatonic or whatever car commercial it was. If Terry Teachout is excited to hear it in McDonald's, good for him. If it can sell cars, it's certainly dandy music to buy hamburgers to:

The Look Of Love

Is in your fries

The look that says

'Supersize ...'

I mentioned above that Hal had said to me how much he admired Irving Berlin for "his confidence to express things simply". But he also liked Berlin as a business model: "Most writers succeed only in one or two areas," David told me. "Rodgers and Porter were basically theatre men. But Berlin did everything. He's unique in that he worked successfully and continuously in all three areas of popular song - shows, films, Tin Pan Alley. Burt Bacharach and I tried that in the Sixties, and believe me, it's tough."

I'll say. By 1968, Bacharach & David had provided big pop hits for Dionne Warwick, Gene Pitney, Cher and many others, and they'd made memorable contributions to What's New, Pussycat? and others of the more grimly groovy films of the period. Their chance to crack that third venue of popular song - the theatre - came when David Merrick signed them to write a Broadway show with Neil Simon. Promises, Promises produced a famous Hal David rhyme. Trying out the show in Boston, Bacharach & David realized they needed a new song for a big scene in the Second Act. Burt was sick. He'd contracted pneumonia. After visiting him in hospital, Hal wrote:

What do you get when you kiss a guy?

You get enough germs to catch pneumonia

After you do, he'll never phone ya

I'll Never Fall In Love Again...

"Pneumonia"/"phone ya" is a cute pairing. But the late comedy writer Dick Vosburgh never tired of pointing out what he saw as one slight problem with it: pneumonia is not a communicable disease. We were once on some terrible BBC Light Ent show together and he brought up the subject yet again, and I remember tossing out alternative ailments to Dick and inviting him to rhyme them:

What do you get when you kiss a guy?

You get enough germs for halitosis

After you do, he won't send roses...

Etc. Today I'd probably throw Dick:

What do you get when you kiss a guy?

You get a dose of Coronavirus

After you do, he's not desirous...

After the show, we were having a drink and Dick revealed that that wasn't his only problem with Hal David. The first time he heard "This Guy's In Love With You", back in the Sixties, was when a friend sang him the opening bars. His ear misunderstood the title phrase as "The Sky's in Love with You":

You see the sky

The sky's in love with you...

"Wow!" he said. "'The Sky's in Love with You'. What an awsome concept." His friend, on the other hand, heard Vosburgh's re-iteration of the title phrase as "This Guy's in Love with You" and couldn't understand why Dick was so bowled over by what seemed entirely conventional boy-meets-girl territory. When their mutual confusion was resolved, and Vosburgh was apprised of the correct lyric, he was less impressed.

Bacharach & David wrote it for a television show. Herb Alpert was the trumpet-playing frontman of the Tijuana Brass, and in 1968 CBS offered him a TV special. He said yes, but he'd like to get his wife on the show, too. But how? Someone said, "Why don't you sing her a song?" So Alpert asked Bacharach & David to write him a song, and they did it as a professional favor with no expectation of ever earning a dime from it. And midway through a CBS special on "The Beat of the Brass", Mr and Mrs Alpert turn up on the beach at Malibu, and Herb sings:

It's often said that Bacharach & David wrote it for their friend's limited vocal skills. And, in a way, that's true: The first line is all the same note, virtually the entire lyric is monosyllabic words, there's not a lot of sustained notes, etc. But, on the other hand, it's quite rangey: It goes down at the end ("if not I'll just die") and way up on the "other" of "know each other very well". I think it would be truer to say that Bacharach wrote the tune for a trumpet player: It sings like a trumpet solo, with a kind of beautiful translucence to its crescendi. In that sense, its musical simplicity is deceptive. For a lyric writer, it presents a different kind of challenge. What do you write that won't seem too complicated for the tune, that will sound, in Hal's words, "as if the singer's just making it up as he goes along"? I think this is the best example of that in the David catalogue. It's what gives "This Guy's In Love With You" its special charm. It doesn't seem like a "love song" so much as a guy coming up with words for a love song extemporaneously. On TV, singing it to his wife on the beach at Malibu, the trumpet player appeared to be "just making it up as he goes along". Of course, if you actually did that, it wouldn't come out this good:

When you smile

I can tell

We know each other very well

How can

I show you

I'm glad

I got to know you?

That's one of only two feminine rhymes in the song. Unlike "pneumonia"/"phone ya", it's not in the least bit clever, and that's exactly why it works. It's true to Hal David's sense that the guy should just sound as if he's improvising the sentiment. Likewise, this next bit:

I've heard some talk

They say you think I'm fine

Yes, I'm in love

And what I'd do to make you mine

Tell me now

Is it so?

Don't let me be the last to know...

That's what David means by the "confidence" to express things simply. Johnny Mercer used to say that writing music takes more talent but writing lyrics takes more courage - because most writers' reaction on putting those words to those notes would be that people would laugh. They don't laugh at the simplicity of the tune, but they quite often jeer at the simplicity of the words that sit on top of it. So the temptation is always to pull back from the simplicity, to complicate the thought, obscure the image. It takes a lot of (as David says) "confidence" not to.

It was a TV variety show moment: There were a lot of them in the Sixties. But, when this show was over, viewers besieged the CBS switchboard demanding to know what that song was that Herb was singing to Mrs Alpert and what record was it on. The thought had never occurred to Alpert, Bacharach or David. "I did it as a favor," said Burt. "I conducted the orchestra, left the Gold Star Studios, and got in the car. If you'd said to me the song would be Number One a month later, I would have laughed." Bacharach & David had had many American hits and two British Number Ones (with Michael Holliday and Perry Como). But this was their first American Number One. Alpert had made the Top 40 many times as an instrumentalist. But this was to be his very first Number One.

They were so good together - until they weren't: a film musical of Lost Horizon turned into a nightmare and bust up the team for good. Bacharach stayed famous and successful and had hits with his new wife and writing partner Carole Bayer Sager. But I don't think "That's What Friends Are For" or "Arthur's Theme" are what anybody has in mind when they rave about how great Burt Bacharach is. On the other hand, whatever one feels about Hal David's "To All the Girls I've Loved Before", some of his other songs with Albert Hammond have something of the same quality as those Bacharach & David songs. Maybe the other guy was more essential to that so-called "Bacharach sound" than anybody realized. I'm especially fond of "99 Miles from LA". Whenever I see Johnny Mathis in concert, I always hope he'll do this one. Alas, he often lets me down a lot in that respect:

In their day, Bacharach & David were regarded as Tin Pan Alley throwbacks, easy-listening guys somehow managing to hold on in an age of rock supergroups and singer-songwriters. Half-a-century on, the Velvet Underground, Jefferson Airplane, you name it, all sound as dated as Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians. But Bacharach & David wound up cooler than ever. "It's like the clothes from the Sixties," said Burt. "They don't work anymore. A lot of the songs don't work anymore." And he flashed me a big, perfect smile. "But some songs do."

You see this guy? His name's Hal David, and writing songs that sound as if you're just saying what's on your mind as it occurs to you is what he did, and very well.

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Paul Simon, Alan Bergman, Lulu, Ted Nugent, Artie Shaw, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Tim Rice, Robert Davi and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is a special production of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and we also have a special Gift Membership.