The conventional narrative has been out there for decades now: at the beginning of the '60s, the old Hollywood order was reeling. The studio moguls were either dying or dead, their audiences abandoning the cinemas for TV and the cities for the suburbs. And then along came Cleopatra – the 1963 historical epic starring Elizabeth Taylor that didn't recover its epic budget despite being a global box office smash.

The cost of making the film nearly bankrupted 20th Century Fox, who laid off all its staff, axed Movietone newsreel production and went into crisis mode. This ricocheted through the rest of Hollywood, and by the end of the decade MGM was selling off its props and costumes and demolishing its backlot. Leaderless and panicking, the studios blinked and allowed a wave of radical new talent inside the gates – names like Coppola, Schrader, Scorsese, Polanski, Altman, Bogdanovich, Ashby, Malick, Rafelson, Friedkin, Lucas and Spielberg, who would reconnect Hollywood with younger audiences and return American cinema to its world class reputation.

If this were a TV documentary, the music cue would bring up Buffalo Springfield on the soundtrack. ("There's something happening here / what it is ain't exactly clear...")

It's the story told in Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, the 1998 Peter Biskind book that would be turned into a 2003 feature documentary. It's a great story, full of folly and triumph and excess, which begins with Boomer underdogs taking over the industry and ends with them becoming victims of their own success. The only problem is that it is, in parts if not on the whole, a myth.

One part that is true is that it was two films – Bonnie and Clyde (1967) and Easy Rider (1969) – whose unlikely success changed the sorts of movies Hollywood would make for the next decade. Easy Rider was directed by Dennis Hopper, an actor who had appeared in the background of films like Rebel Without A Cause and Giant for over a decade, and who never repeated his success as a director due to a prodigious collection of personal demons.

Bonnie and Clyde – the first major tremor in the Hollywood youthquake – was made by Arthur Penn, a director who almost never gets namechecked along with Coppola, Scorsese and the rest, despite playing such a key role in creating the myth of the Young Turk takeover of Hollywood.

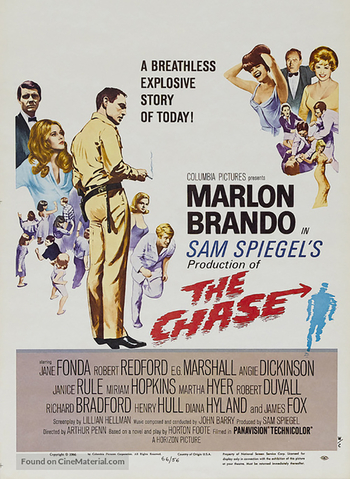

A year before Bonnie and Clyde was released, Penn had directed another picture – a star-studded drama about an escaped prisoner and a small town that went crazy. The Chase was a mixture of Peyton Place, Inherit the Wind, In the Heat of the Night and To Kill A Mockingbird, the sort of melodramatic potboiler brimming with social issues that got made a lot during the Sixties. It was topical, violent and sensational, but it didn't change the movie industry.

Over the opening credits we watch as "Bubber" Reeves (Robert Redford) escapes from the state penitentiary with another inmate who murders a man and steals his car, leaving Bubber to take the fall and make his way to freedom on foot. He hops on a train going the wrong way, however, and finds himself outside his unnamed hometown, in fictional Tarl County, Texas.

Redford's Reeves is an impossibly good-looking fugitive, and he's not asked to do much as the movie's McGuffin – Alfred Hitchcock's famous term for a plot device exists to do little more than move the story along. News of his escape filters through the town, introducing us to the town's sheriff (Marlon Brando) and his wife (Angie Dickinson), Bubber's wife Anna (Jane Fonda, in a role Faye Dunaway didn't get) and his parents (the mother played by Miriam Hopkins, last seen in this column over thirty years earlier in Ernst Lubitsch's Design For Living.)

Bubber's wife has been having an affair with Jake Rogers (the utterly British James Fox attempting a Texan accent), only son of Val Rogers (E.G. Marshall), the plutocratic boss man of the town, owner of the bank on main street as well as oil wells and farmland all over the county. The trio were childhood friends, but as poor whites in the town's caste system, it was easier for Anna to marry Bubba than Jake, the man she really loves.

As the news spreads we meet most of the rest of the town, a largely irredeemable rabble that includes milquetoast Edwin (Robert Duvall), one of the bank vice presidents, whose sexy and neglected wife (Janice Rule) is brazenly having an affair with the other vice president. At a gala fundraising birthday party that night for Mr. Rogers, the county's wealthy sycophants line up to pledge money to the eponymous university Rogers is building, so that young people like his son won't ever have to leave Tarl County to get an education.

The gala is a gallery of grotesques, only outdone by the convention of dental supply salesmen in town for the weekend and the crowd at a Saturday night party at Edwin's house – a drunken near-orgy crammed with the town's white middle class, some of whom take the opportunity to leer at the teenagers having a frantic dance party in the house next door. The only black characters we meet either do their best to stay out of the way of whites or suffer their belligerent attentions, while the Mexicans are mostly migrant labourers who we see shipped off back south in the opening scenes.

As sightings of Bubber filter back to the townsfolk, tensions ratchet up with the boozing, which the sheriff struggles to control, hampered by the general assumption that since he was appointed to the job by Rogers, he's in the rich man's pocket. News that Bubber is hiding in a junkyard outside town sends this whole crowd of drunks, bullies, sluts, peckerwoods, bigots, cuckolds and inbred ninnies converging in a convoy of cars on Bubber, Anna and Jake. By this point it's obvious why any sane young person would want to leave Tarl County.

The Chase was made during the long, frustrating start of Arthur Penn's career as a director. His first film was a 1958 western, The Left-Handed Gun, starring Paul Newman as Billy the Kid. He was unable to edit the film himself, and after handing off the footage to the studio, next saw it at the bottom of a double bill in New York City. The film mysteriously acquired a following among auteur-obsessed French cineastes, which encouraged Penn's artistic ambitions even if it did little to advance his career in Hollywood.

Penn (who died in 2010) was an intellectual who grew up in Philadelphia, the younger brother of acclaimed fashion and portrait photographer Irving Penn. He discovered theatre during his military service, and would split his time between directing plays and television in New York in the '50s. After opening The Miracle Worker on Broadway he was asked to make the acclaimed 1962 film adaptation, but got kicked off The Train, his next film, after disagreements with star Burt Lancaster.

Mickey One (1965), his fourth picture, starred Warren Beatty in the surreal story of a stand-up comic on the run from the mob. Heavily influenced by the French New Wave who had embraced his first film, it was a flop that confounded critics, but developed a cult status when the picture was rediscovered in the mid-'90s and praised as a "jazz film."

The Chase began as a play and a novel by writer Horton Foote, cousin of historian Shelby Foote, who wrote the text upon which Ken Burns based his hit PBS TV series The Civil War. (Horton Foote would be the onscreen voice of Jefferson Davis.) Foote, who wrote the screenplay for To Kill A Mockingbird, is considered a reputable teller of stories set in the American South, so it has to be assumed that the violent melodrama and potboiler expansion of Foote's play to include the lawless, vengeful townfolk came from screenwriter Lillian Hellman.

Hellman's reputation is much diminished now, but she was once a famous and divisive figure. Her career in Hollywood started in the '30s, and she sold furs in Blackglama's "What Becomes A Legend Most?" ad campaign in the '70s, alongside stars like Audrey Hepburn, Lucille Ball, Mary Pickford and Barbara Streisand.

New Orleans-born Hellman wrote Broadway hits, won an Oscar and was the partner of crime novelist Dashiell Hammett from 1931 until his death. She was also a blacklist victim, and either an unrepentant Stalinist or a fellow traveler who refused to implicate friends when called to testify in front of HUAC, depending on who you believe.

It wasn't just her politics that made her enemies; journalist Martha Gellhorn said that Hellman made up most of her stories about Ernest Hemingway, Gellhorn's third husband, when writing about the Spanish Civil War in her memoirs. Muriel Gardner, a New York psychiatrist, claimed that Hellman had stolen her story for the character of Julia in her memoir Pentimento, and that she had never known Hellman. (Jane Fonda got an Oscar nomination for playing Hellman in the 1977 film Julia, with Jason Robards winning for his portrayal of Hammett.)

While appearing on the Dick Cavett Show, writer Mary McCarthy famously said of Hellman that "every word she writes is a lie, including 'and' and 'the'." Hellman sued McCarthy, Cavett and PBS for defamation, though the suit was dropped by her estate after her death in 1984.

Hellman's script loads up Foote's much more primal story about duty, revenge and guilt with presumably significant details that come out of left field, like the fact that at least three of the couples in the story, including Jake and his wife and Brando and Dickinson, are regrettably childless. She also has to take credit for the dialogue, none of which is subtle:

"I guess you're all a sek-shul revolution all by yuhself."

"Shoot a man for sleepin' with someone's wife? That's silly. Half the town would be wiped out."

"Do you believe in the sek-shul revolution Mr. Rogers? Because mah husband does."

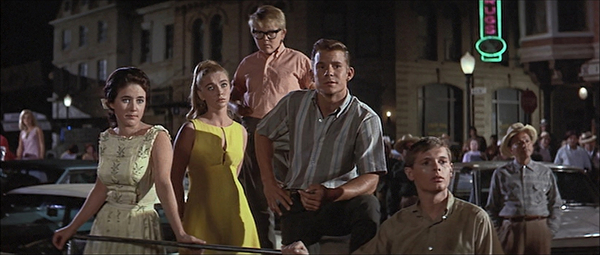

Her most curious addition to the malevolent chorus of townsfolk are the kids – a group of spoiled, semi-feral youth who frug like demons and travel around in a hot rod jalopy. (Prominent among them is singer and songwriter Paul Williams, 25 years old but playing a teen, and just a few years from his chart-topping run of hit songs.)

A film made a few years later would be more sympathetic to the kids, perhaps giving them screen time to express their disgust at the hypocrisy of the town's adults. But in Hellman's script they're just lumpen versions of their white collar redneck parents; they even get the honour of setting off the fiery junkyard götterdämmerung at the climax with flares and improvised Molotov cocktails.

And Hellman can definitely take credit for the brutal onscreen beating that Brando's sheriff endures from three of the town's citizen bullies – a bloody scene that's painful to watch today, and must have been shocking in 1966 – though Penn's direction and Brando's commitment to "the method" does a lot of the work making you wince with every punch.

As a student in a first-year university film appreciation class in the early '80s, I remember being quite shaken by this film I'd never heard of before. Untraveled, poorly read, and with life experience that can best be described as peering at the world through a slit in a wall, it confirmed prejudices that I'd been encouraged to have – about adult life, Americans, and the South in particular. Today it plays with a lugubrious sluggishness up until the explosion of violence at the end, overcooked and top heavy with overused stereotypes, a high class dry run for what would follow years later in an avalanche of hicksploitation pictures, and the sort of movie that thinks nothing of insulting wholesale a third of its potential audience.

The Chase did nothing to improve Penn's relationship with Hollywood. Producer Sam Spiegel took the film away from him for editing, and he would dismiss it years later, saying that "everything in that film was a letdown." He might never have directed another film if not for Warren Beatty's insistence that he work on Bonnie and Clyde a year later.

Penn was less critical of the film when I met him in the mid-'90s, in an empty hotel banquet room during the Toronto film festival. Apparently having a hard time attracting attention for his latest film, a publicist made a point of introducing me to him. I froze for a second, debating with myself whether to mention his brother, whose work I idolize as a professional photographer.

I wisely chose not to, but stuttered out something about being really taken with a film he'd once made, "a little picture called The Chase."

Penn immediately reacted, his voice registering protest and dismay.

"That was hardly a little picture – there were some really big stars in that film..."

Thankfully the publicist returned to distract Penn, and I learned never to meet anyone like him without prepared remarks. I'd have been better served if I'd have seen later pictures like Night Moves (1975) or Penn & Teller Get Killed (1989). For some reason I didn't remember that Penn was the man who'd made Bonnie and Clyde – not all that surprising considering how his reputation did a slow fade during the '70s, when directors like Coppola, Spielberg, Lucas and Scorsese were on the rise. It just underlines the crucial role Arthur Penn played in kicking off the rock and roll takeover of Hollywood, despite being a transitional figure, out of the earlier jazz age.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below. Access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club. Kick back with your fellow Club members in person aboard our third Mark Steyn Cruise, featuring Michele Bachmann, John O'Sullivan, Conrad Black and Mark himself, among others.