If you're just joining us, this is Part IV of an ongoing series about how patriots can take back their country (see parts I, II, and III). (Thanks all for joining in the fun in the comments section.)

My first thought when I considered how patriots might take back their country was, know thine enemy. You know, Sun-Tzu and all. Seemed sensible enough.

So, I threw out a few of my own ideas about Wokism's nature and causes, then wound up mining a classic of political psychology, Erich Fromm's 1941 Escape from Freedom, for any additional insights.

Fromm contends that the great freedom created by modern society can leave people feeling isolated, anxious, and insecure. Some of those people will seek to overcome their painful feelings by immersing themselves in authoritarian, destructive, conformist political movements—like Wokism. That is, they will seek an escape from freedom. They will even seek to destroy it.

If Fromm is correct, it's not just that, in great amounts, freedom enables anti-freedom movements like Wokism to arise, as per Popper's Paradox of Tolerance. It's that it makes them inevitable. On this view, too much freedom begets the dissolution of freedom.

This sounds plausible enough, if unpleasant. And it would be natural to hope Fromm has some equally plausible solution to lead us out of this mess.

As it happens, that turns out not to be the case. To summarize Fromm:

The cure for isolation, anxiety, and insecurity is to achieve what he calls "the realization of self". We do that by practicing spontaneous activity at all times, "like the artist". We thereby overcome all the human needs which would otherwise drive us toward the escape from freedom. Along the way, we must avoid faith in something higher than ourselves—like God. "There is no higher power than this unique individual self...man is the centre and purpose of his life", he says.

As I would characterize it, Fromm's "solution" for the problem of human beings who choose to escape from freedom amounts to a demand that human beings just choose not to escape from freedom. That is, Fromm's solution is for human beings to become what they are not, and cannot ever be: something more than human. Or put another way: not human.

For one would be more than human—that is, not human—if one could simply choose to avoid all thought of, all inclination toward, a Higher Power or purpose. Same as if one could simply will oneself out of feelings of isolation, anxiety, and insecurity upon their first appearance; will oneself away from all the obvious, at-hand remedies; and will oneself into a permanent state of "spontaneous activity" instead (whatever "spontaneous activity" might even mean).

Fromm avoids the question of why anyone would actually want to will something like this in the first place. Why would any human being suffering in the way Fromm describes want to attempt the seemingly impossible (and painful in itself) task of wholly overcoming his own humanity, when there are alluring practical remedies at hand—like succumbing to a "one true" political movement devoted to heaven on earth? How can we reasonably expect everyone to have prior understanding that, say, Wokism is a dangerous fraud, as well as the ability and will to reject it beforehand in favor of something called spontaneous activity?

No—this is all nonsense. Fromm's original diagnosis seemed unobjectionable enough. But his "cure" amounts to a glib, impossible demand that we transcend constraints embodied in our own biology—that is, that we transcend our own humanity; that we become magic.

We must, in some unexplained way, know what we do not know, so as to want what we do not ultimately want, so as to do what we cannot do and become what we cannot become: a superhuman free from human nature itself, unencumbered "by any power outside himself", and who therefore now gloriously, happily inhabits an entirely new realm of superhuman freedom as a "fully realized self"—albeit in a society of other transformed, superhuman, unencumbered selves. (That membership in a society necessarily entails forms of encumbrance is a fact Fromm leaves unacknowledged).

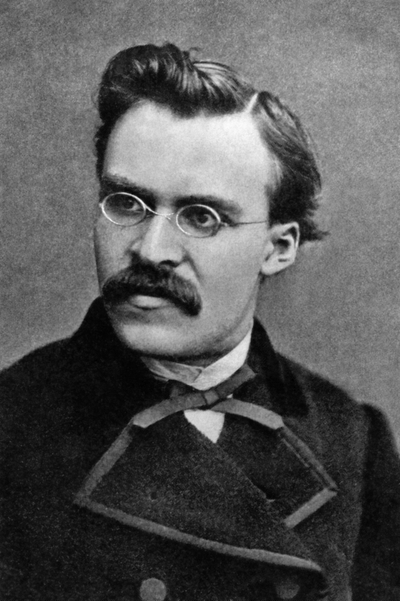

As I say, this is all nonsense. But it is also an odd tack to take for a German Jew who had only recently fled Nazi Germany. One reason is that it amounts to a reworked rendition of Nietszche's concept of the Übermensch—the "superior man" who has transcended his own humanity, and now chooses his own values, his own fate, and his own complete freedom to act and create.

First introduced in his 1883 book Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche's Übermensch channels the eternal Dionysian spirit. He inhabits a higher plane. Everything he does is a work of highest art simply because he has done it. He has become a god, boldly and spontaneously acting as he wills, constrained by nothing. No obstacle stops him. He chooses his own values, his own powers, his own fate. He is an early version of Fromm's transformed man.

Yet the National Socialism from which Fromm had just escaped drew much of its ideological fuel from a racialized rendition of this very concept.

Certainly Nazi theorists had plenty of contemporary science to draw on: it was the Nazis who first pioneered the old "follow the science!" trick for engineering mass conformity of opinion, repeatedly invoking cutting edge scientific, particularly evolutionary, thinking on the relative merits of the races and the moral requirement of eugenics to realize their goals.

But it was the powerful flood of philosophical ideas—not least of which were those, like Nietzsche's, which preached man's ability and duty to transcend himself—which propelled much of National Socialist fervor.

All of which is to say that you'd think Fromm might pause before reworking the Übermensch concept. Alas, he didn't. That's especially strange, since Fromm devotes an entire chapter in Escape from Freedom to discussing the psychology of Nazism.

But Fromm passes from strange to grating—it might be better to say pernicious—when he acknowledges that the supreme freedom enjoyed by his magical Übermensch "has never been realized in the history of mankind", yet still insists without substantiation that this supreme freedom is not only realizable, but must be realized.

Why? On what grounds does Fromm conclude any such transformation, and any such supreme freedom, is possible? Or desirable? Or morally obligatory?

The answer is the plot twist. It is that Fromm himself had already succumbed to just the kind of ideological cult he warned others about: plain old Marxism, the progenitor of the Wokism which afflicts us now.

A member of the Frankfurt School, Fromm early on imbibed Marxism and never shed himself of it. Every discovery or insight he made for the rest of his life required reconciliation with the "one true truth" he had already accepted. No atrocity committed by Marxists, in the name of Marxism, could be laid at the feet of The Master Himself. The Master is always blameless. It is The Master's benighted, fallible disciples who mess everything up. At the end of Escape from Freedom, we even get to hear Fromm dismiss the failed experiment that was Soviet communism as not really communism (translation: Still no evidence has sullied The Unsulliable Master). Fromm even goes so far as to say that his proposal for "the realization of self" through the transcendence of our own humanity requires "a planned economy".

And so, we must conclude our consideration of Fromm recognizing that while he offers a few nice insights into the psychological drivers of Wokism, his eventual descent into a dangerous, child-like, Marxist fantasism precludes him from offering any positive suggestions for how to combat it.

And that leaves us back where we started, unsure exactly how we got here, and unsure how to get out.

But that's okay. Next time, we'll explore a different, perhaps more promising, intellectual path and see if that gets us any farther. At least we're on this journey together. And that's something, at least, isn't it?

Tal will be back here next week to continue the conversation. If you can't wait that long, he'll be performing alongside Randy Bachman tonight over at Bachman and Bachman, starting at 9pm ET.

Tal will be among Mark's special guests on this year's Mark Steyn Cruise down the Mediterranean. Join him and Douglas Murray, Conrad Black, and Michele Bachmann, among others, for 10 nights of relaxation and review. Staterooms are available here. Mark Steyn Club members can weigh in on this column in the comment section below, one of many perks of club membership, which you can check out here.