Fourteen months of lockdown have produced a fierce longing for escape. Travel is forbidden, of course, and the people running my city have intermittently made outdoor spaces like parks and even cemeteries out of bounds, along with all the restaurants, bars and shops I haven't been inside since early last year.

So I've made my escape into the past, into a world that resembles my own as little as possible – a world of wit, eccentricity, screwball antics and occasional elegance. The world of the Hollywood comedy of the '30s and '40s.

It was either that or westerns, and I sunburn too easily.

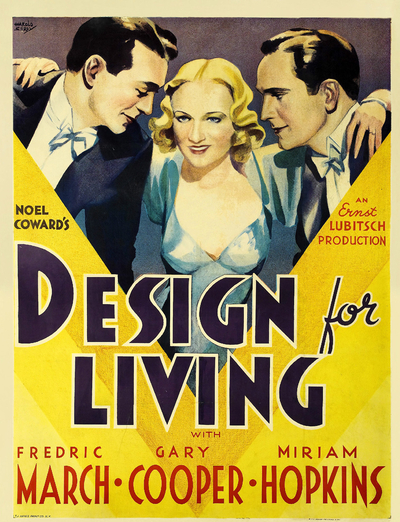

Design For Living was released in 1933, before the enforcement of the Hays Code, so it's always cited approvingly on lists of films that affronted the moral arbiters of the day. I don't want to try to make a case for the superiority of Pre-Code films – it's been made too often, never convincingly, and in any case the wit and ingenuity required to work with and around the Code really made Hollywood's Golden Age truly golden.

Directed with typical ease by Ernst Lubitsch from a play by Noel Coward, Design For Living is a film where the main characters are in tuxedos and evening gowns for much of their time onscreen, in homes that could exist nowhere except on a soundstage. It's a world where, a few doors down, Fred and Ginger would be dancing, and it even shares Edward Everett Horton, playing the same sort of fussy, effete foil.

It's the story of a trio of bohemian types – struggling artist George (Gary Cooper), unproduced playwright Tom (Frederick March) and illustrator Gilda (Miriam Hopkins) – who meet in the third class compartment of a train to Paris and instantly fall for each other. George and Tom share a garret room, Gilda works in advertising, and after a giddy mating dance they agree to form a platonic triad, with Gilda as their muse and "Mother of the Arts."

The only impediment is Plunkett (Horton) – Gilda's occasional employer and frustrated suitor, whose defense of her virtue from their threadbare assault is easily overmatched by March and Cooper's masculinity. Gilda is a fine Mother in any case, inspiring Tom and George but also acting as their promoter and agent, securing Tom a London opening for his play and George a career as society portraitist.

Their "gentleman's agreement" to refrain from sex doesn't survive Tom's trip to London, when Gilda collapses supinely onto a settee under the weight of the sexual tension with George, pleading that she is, after all, "no gentleman."

The film roughly follows the storyline of Coward's play – a hit when the actor/writer performed it with superstar theatre couple Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne filling out the ménage a trois – but only a single line of Coward's dialogue survived the transformation into film by Ben Hecht, one of Hollywood's legendary screenwriters.

Hecht was a character in his time, and would be considered outrageous and outsized today. He was born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan to Jewish immigrants, who moved to the Wisconsin wilderness before he was a teenager, where he lived the ungoverned, pre-suburban youth celebrated by Mark Twain. Hecht read voraciously and indiscriminately, and landed a job as a cub reporter in Chicago, stealing photos of murder victims from their grieving families. This was a time when journalism schools weren't around to civilize and accredit junior reporters, and the rude and chaotic newsroom experience formed Hecht's worldview.

"We who knew nothing spoke out of a knowledge so overwhelming that I, for one, never recovered from it," he wrote in his 1954 autobiography, A Child of the Century. "Politicians were crooks. The leaders of causes were scoundrels. Morality was a farce full of murder, rapes, and love nests. Swindlers ran the world and the Devil sang everywhere. These discoveries filled me with a great joy."

Hecht wrote short stories and began moving in a literary crowd that included Theodore Dreiser, Carl Sandburg and the Algonquin circle, before getting the famous telegram from screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz (Citizen Kane, The Wizard of Oz) that beckoned him to Hollywood, where "millions are to be grabbed" and "your only competition is idiots."

His first script was for Underworld, a 1927 gangster film directed by Josef von Sternberg which won him an Academy Award. The next year he co-wrote a play, The Front Page, with his pal Charles MacArthur – an endlessly revived newspaper comedy that would be remade perfectly by Howard Hawks as His Girl Friday. After inventing the gangster picture with Underworld, he defined it for all time in 1932 with Scarface. Hecht went from hit to flop to hit, cashing cheques and often eschewing onscreen credit, insisting that he detested working on movies and referring to Hollywood as "an outhouse on the Parnassus."

Hecht's character and experience made him sympathize with bohemians and lowlifes, rogues, affable losers and thugs, and he created rich social milieus around the leading men and women that usually interested him far less. In Design For Living he has an obvious fondness for the trio of expat struggling artists, and especially Frederick March's Tom. It's no surprise that the man who wrote The Front Page would happily amplify the qualities of characters that Noel Coward would later describe as "glib, overarticulate and amoral."

Tom, confronted by Plunkett about his intentions with Gilda, responds with tartness and a hint of menace:

Oh, now don't let's be delicate, Mr. Plunkett. Let's be crude and objectionable, both of us. One of the greatest handicaps to civilization, and I might add to progress, is that people speak with ribbons on their tongues. Delicacy, as the philosophers point out, is the banana peel under the feet of truth.

Hecht's affection for Tom, George and Gilda isn't blind. He makes it plain that neither of the men are truly gifted, and it's only Gilda who has any real talent, albeit for inspiration and hype. Their great talent is their youth and attractiveness, echoed by similar trios in films to come, like Truffaut's Jules et Jim and Bertolucci's The Dreamers.

Cooper is often considered miscast as George, but his doggish roughness is a great counterpart to March's loquacious and self-impressed Tom. Hopkins, a largely forgotten actress today, has an idiosyncratic but striking beauty, all high forehead and firm jaw and streamlined figure, like a gilded Art Deco figurine in a cocktail dress.

Both Lubitsch and Hecht set the model for the next decade's worth of comedies, screwball and otherwise, with smart, attractive, often unpredictable women as the force of nature at the centre, played by actresses as different as Hopkins, Katharine Hepburn, Myrna Loy, Jean Arthur, Claudette Colbert, Rosalind Russell, Irene Dunne, Barbara Stanwyck, Constance Bennett and Carole Lombard.

Tom, George and Gilda are intoxicated by each other, with proximity a multiplying effect on their attraction; Coward described them as being "like moths in a pool of light." And even if we can see callow youth and folly for what it is, it's hard not to be swept up in the knowing way Hecht lets them analyze their fragile and probably unworkable situation.

Self-referential post-modernism is nothing new; it only had to wait for mediocre minds to turn it into a brand. But it's at work in exchanges like this one, between Tom and George, after the latter starts breaking things upon realizing that his friend spent the night with Gilda while he was away.

Tom: That's one way of meeting the situation. Shipping clerk comes home, finds missus with boarder. He breaks dishes. Pure burlesque. Then there's another way: intelligent artist comes home unexpectedly, finds treacherous friend. Both discuss the matter in grown up dialogue. High class comedy. Enjoyed by everybody.

George: And then there's a third way. I'll kick your teeth out, rip your head off and beat some decency into you.

Tom: Cheap melodrama. Very dull.

You don't have to like anyone in a comedy to find them funny. Better that the laughs come where familiarity edges into contempt – so long as you understand that familiarity is recognizing yourself in the laughter. We might not all have been as good looking as Tom, George and Gilda, but we were once that young and foolish and certain of our unkillability that we could defy the laws of nature, human and otherwise. Tom would like to live in a high class comedy; George is happy with cheap melodrama. Perhaps only Gilda has an inkling that it might turn out to be neither, and nowhere near as fun.

She leaves both men after their argument and marries Plunkett, but her escape into respectability, boredom, and "100 per cent virtue and three square meals a day" doesn't survive Tom and George returning from China, friends again, to crash a party for Plunkett's geriatric clients in his upstate New York mansion. She leaves her husband with sage advice on how to retain his clients after the offscreen dust-up in the parlour, puts on her fur and departs with Tom and George for their old garret in Paris.

Apologists for "enlightened" libertinage and the allegedly superior, more "honest" morality of Pre-Code films like to celebrate the merry exit of the polyamorous trio in Design For Living, laughing in the back of their taxicab. But it's worth noting that the last thing they do is renew the "gentlemen's agreement" that did not long survive the first time they swore to it.

Imbalance of power and the hoarding of grievances are usually the death of relationships. It's hard to manage them in a couple, harder in a trio – especially one where one person will always have final veto. Gilda, clearly the smartest of the three, is also "no gentleman."

They'd probably last a lot longer in Coward's version of the story (far less heteronormative, as the kids say these days) but nonetheless it's a challenge to imagine a long collective epilogue for Tom, George and Gilda. There are, after all, a lot of convenient Plunketts in the world, and a smart woman might even be able to transform a Tom or George into one with time. (My money's on Tom, who would probably come to enjoy 100 per cent virtue and three square meals a day.) Our lovestruck trio might have met in a third class compartment on a Pre-Code train, but their taxi is driving them off to a Code world.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below. Access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club. Kick back with your fellow Club members in person aboard our third Mark Steyn Cruise, featuring Michele Bachmann, John O'Sullivan, Conrad Black and Mark himself, among others.