The hundredth anniversary of Northern Ireland this past week prompted one American correspondent to email:

Is this actually a thing?

Well, yeah, actually it is. The Government of Ireland Act, which came into force on May 3rd 1921, created two new jurisdictions within the United Kingdom - Northern Ireland, which celebrated its hundredth birthday this week, and Southern Ireland, which chose to embark on a different course...

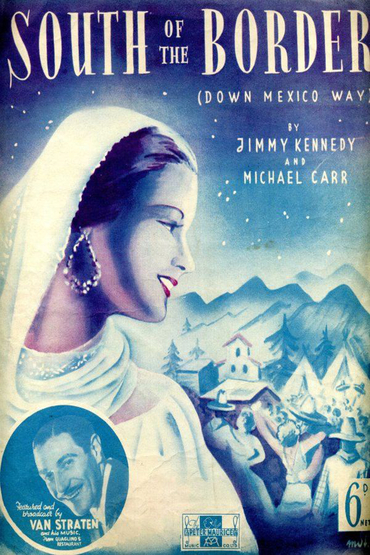

So on this Ulster centennial how about a song from the first great songwriter to come out of Northern Ireland? And, in a spirit of cross-community healing, how about we pick one he wrote with a fellow from the south? Jimmy Kennedy was born in Omagh but grew up in Coagh, and eventually settled in Portstewart on Ulster's beautiful north coast; Michael Carr was born in Leeds but raised in Dublin: They were both teenagers in their respective corners of the Emerald Isle during the turbulent events of a century ago. Throughout their careers in Denmark Street, Britain's Tin Pan Alley, both men wrote both words and music, but in this case most of the lyric came from the guy north of the border, and most of the music from the fellow down south. And, as you can tell from the title, "South of the Border" is a searing tale of love across the sectarian divide on a small island off the north-west coast of Europe:

Whoops, my mistake. Kennedy and Carr certainly wrote Irish numbers, including "Did Your Mother Come From Ireland?" (to which question both men could answer yes), which is certainly a very apt theme for this Mother's Day:

The genius of that song is that, although it was written by two genuine Irishmen, it sounds as fake as any of the Tin Pan Alley stuff full of synthetic shamrock made in a factory in Wuhan or wherever. Notwithstanding the above, the bulk of Carr and Kennedy's hits surveyed a broader horizon. Frank Sinatra recorded Jimmy Kennedy's "Isle Of Capri" for Come Fly With Me, and, although he never got to Kennedy's "Istanbul (Not Constantinople)", for a goofy novelty song it's attracted an amazing number of recordings by all kinds of other people. "April In Portugal" hasn't endured quite as well, and the Tommies' wartime chin-up song "We're Going to Hang Out the Washing on the Siegfried Line" didn't work out as planned, but both testify to Jimmy Kennedy's propensity to roam far and wide lyrically. Nevertheless, Carr and Kennedy's great song of place is "South Of The Border", and in the early Fifties Sinatra's terrific record helped revitalize both his career and the fortunes of a semi-forgotten cowboy ballad.

Carr was born in 1905 to one of those much serenaded Irish mothers and to a prizefighter called Cockney Cohen, who, post-boxing, had moved to Dublin and opened a restaurant. Kennedy was born three years earlier to his own Irish mother and a policeman in the Royal Irish Constabulary at Omagh. One day Jimmy was sitting on the shore near the Portstewart harbor and noticed a small yacht lazily sailing into the west as the sun met the horizon. So he wrote a song called "Red Sails In The Sunset", and it was a hit for Al Bowlly and Ray Noble. The yacht was called Kitty of Coleraine and, if you're ever in Portstewart, you can see a handsome memorial commemorating ship, song and writer, and find the yacht itself beautifully restored and on display in a local museum.

Michael Carr went Jimmy Kennedy one better. When he was 15, Maurice Cohen (as he then was) was down by the harbor at Dun Laoghaire, saw a ship, and decided to run away to sea. He wound up in America, where he spent a few years as a journalist and then, as "Michael Carr", a bit-player in Hollywood movies. In the early Thirties, he meandered back across the Atlantic and washed up in Denmark Street, the heart of the British music business just off the Charing Cross Road. The publisher Peter Maurice paired him with Jimmy Kennedy, and a very odd couple they made. In his entertaining autobiography of his father, JJ Kennedy describes Carr as "what the Irish would call a chancer". He was always broke and prone to implausible, improvised schemes to alleviate his skintness. Jimmy Kennedy, by contrast, was very businesslike. I met him toward the end of his life, and I recall him as an extremely dapper and organized man. The relationship with Carr was not easy. As Kennedy told his son:

Although Michael Carr was talented, he was crazy and difficult. We would start a song and then he would disappear. Then Jimmy Phillips would ask to see what we had produced and I would have to finish it myself. That would lead to a row for all kinds of obvious reasons, not least the fact that he would still get his share of the royalties, regardless of how little effort he put into it. Our professional relationship was quite different from the one I had with Will Grosz [the composer with whom Kennedy wrote "Isle Of Capri"] in that Grosz was first and foremost a musician but Carr and I both wrote words as well as music. Carr always wanted to produce the big line and so did I. Then he would want to get the tune right and I would find myself correcting it. So there was an endless battle going on. I think a fundamental reason why we were so successful was because our characters were so opposed, it made us determined to prove we were better than the other - and that spurred us on to better and better ideas.

One day, at the end of the Thirties, Carr showed up at the office and announced to Kennedy that he had a great tune for a western. He sat down at the piano and played the first few bars, and Jimmy didn't think it sounded that western. Notwithstanding that it has the same bass pattern – the one that serves as a useful musical shorthand for a cowpoke moseying along a sagebrush trail on his faithful ole paint –that you find in Michael Carr's other forays into the genre like "Sunset Trail" (written with Jimmy Kennedy) and "Ole Faithful" (written with Jimmy's brother, Hamilton Kennedy), Jimmy thought this one sounded less western than Spanish. Which reminded him of a postcard he'd received a few days earlier from his sister Nell halfway round the world in California. It began:

Today we've gone Mexican – we're south of the border...

Kennedy knew a hit title when he heard one. "What about," he suggested, "'South Of The Border'?" To which Carr responded immediately: "'Down Mexico way!'"

And they were off:

South Of The Border

Down Mexico way

That's where I fell in love

When stars above

Came out to play...

That afternoon, Kennedy wrote the middle section:

Then she sighed as she whispered, 'Mañana'

Never dreaming that we were parting

And I lied as I whispered, 'Mañana'

For our tomorrow never came...

That's Jimmy Kennedy, words and music. Presumably, Michael Carr never came back from the pub after lunch. It's very good, but, even before I knew it wasn't Carr's music, it always kinda sounded separate to me: not one of those releases that arises organically from the main theme, but something entirely different. (The "I saw your face and I ascended" bit in "Stranger In Paradise" always had the same effect on me, sounding very different from the main theme, adapted from Borodin's "Polovtsian Marches". Years later, Wright & Forrest told me, "We wrote that part ourselves. We'd run out of Borodin. There wasn't any left.")

Still, it sounded pretty good and, rounding things out with a few "Ay-ay-ays" just to underline the point, Kennedy & Carr had a song:

That was the very first recording - May 5th 1939 - by the British bandleader Billy Cotton with the unmistakeable vocal strains of Alan Breeze. Kennedy & Carr had bigger, American plans for the song. The only problem was that their boss, Jimmy Phillips, didn't care for it. His big hit that month was going to be "The Same Old Story" by Eric Maschwitz. A BBC radio producer who moonlighted as a songwriter, Maschwitz left us two great standards, "These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)" and "A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square". Compared to those gems, "The Same Old Story" was the same-old same-old.

Some weeks later, Kennedy & Carr noticed that Gene Autry was over on tour, and arranged to see him backstage in Dublin, where they pitched him "South of the Border (Down Mexico Way)". Neither man had ever set foot in Mexico, and Autry might reasonably have wondered why he should have to have songs about his native terrain peddled to him by a couple of foreign opportunists. But for a pair of Irish Denmark Streeters these two had between them notched up an impressive number of hits in America, including stuff explicitly aimed at Autry's singing-cowboy beat such as "Roll Along, Covered Wagon". He listened to Kennedy & Carr's song and liked it. And so, while this song might not sound terribly Irish, unlike "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling" et al, with this one they at least sealed the deal in Ireland's capital city. And, when he got back to America, Autry went into the studio in Chicago and, over September 11th and 12th 1939, recorded half-a-dozen numbers, including "South Of The Border":

Autry's record was a hit, as were versions by Guy Lombardo & his Royal Canadians and Shep Fields & his Rippling Rhythm, and "Your Hit Parade" listeners voted it the best song of the year. Republic Pictures liked it, too. They bought the film rights for a thousand bucks and built a Gene Autry movie around it:

What was that date Gene Autry was in the studio in Chicago? September 11th and 12th 1939. On September 1st, Germany invaded Poland, and Britain declared war. Both Kennedy & Carr joined the army. Jimmy Kennedy had a good war – I don't mean just that he rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Artillery, but that, while in the army, he wound up composing one of the monster hits of the age: "The Cokey-Cokey", which semi-de-coked became a British wartime favorite as "The Hokey-Cokey" and then, for obscure reasons, got wholly de-coked for America as "The Hokey-Pokey".

For Michael Carr things sputtered along somewhat more fitfully during the war years, starting with what was undoubtedly the worst business decision he ever made. In 1939, he was, as usual, strapped for cash, and, needing a few quid to tide him over, sold his rights to "South of the Border" to his publisher for a lump sum. That very first Gene Autry record alone sold three million copies. The sheet music was a million-seller. The song was never as big in Britain, although the Shadows got some mileage out of it in 1962, but in America it never stopped being sung and never stopped selling – Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Perry Como, Bing Crosby, Mel Tormé, Patsy Cline, Connie Francis, Herb Alpert, Chris Isaacs... And Michael Carr never saw a penny from any of it.

As for Frank Sinatra, he'd been singing "South Of The Border" since it was new, live and on the radio if not on record. Some day, some wily record exec is going to release a CD called Sinatra Exotica or some such, because there's a kind of song that's been present in his oeuvre since the beginning, since "On a Little Street in Singapore" with Harry James in 1939, and "Pale Moon", his very own Indian love call with Tommy Dorsey in 1940. That type of material went away for a while, as Sinatra went solo and focused on less over-ripe romance. But in 1953, starting out at a new record company, Frank was in the mood to indulge that exotic side. His first session at Capitol Records, with his longtime arranger Axel Stordahl, had been ...okay. But the records hadn't sold, and the company thought the Sinatra style needed shaking up a bit if he was going to pull out of that early Fifties tailspin. A new arranger was the answer. So Sinatra's producer Voyle Gilmore called Billy May and offered him the gig. Unfortunately, Billy was on tour and had to say no, so Gilmore asked if he'd mind if they called in another arranger to arrange the songs in Billy May style. "Sure, go ahead," said May, as long as they gave him a percentage.

When I was at the BBC many years ago, one of my colleagues was Alan Dell – we shared a producer for a while, although no one ever really produced Alan. But before his broadcasting days he'd worked for various record companies, and in the early Fifties he was under secondment to Capitol in Los Angeles. And so he chanced to be running that second Sinatra session for Capitol on April 30th 1953. And this is how Alan told it to me at one ghastly BBC cocktail party in either the Chairman's or the Director-General's suite at Broadcasting House many Christmases ago: Frank walked into the studio expecting to see the luxuriantly-sized Billy May at the conductor's podium. Instead, there was a somewhat svelter figure. "Who's that?" asked Sinatra, who was used to being screwed over and inclined to suspicion. "Oh, he's just conducting," said Alan. "Don't worry, we've got the Billy May arrangements."

Frank relaxed. In those days, Sinatra liked to rough out the arrangement and even the general lie of the orchestration himself, and he'd based his view of "South of the Border" on a version he'd done on the radio with Spike Jones in 1944. Great, said Capitol, and, as far as Frank was aware, they'd passed it along to Billy May to get cracking on it. And, when the fellow on the podium waved his stick and Frank started singing, he had to admit that Billy had done a helluva job on the chart. Those slurping saxes were great. And getting the band to ay-ay-ay along with him at the end – what a gasser!

As always when he was having a ball, Sinatra took a few lyrical liberties in the reprise of the chorus. So south of the border, instead of riding back one day, Frank jumps back:

I jumped back one day

There in a veil of white

By candlelight

She knelt to pray

The mission bells told m

That I must not stay

South Of The Border

Down Mexico way!Ay-ay-ay-ay

(Ay-ay-ay-ay...)

Etc. So one encounter with Frank drove this dame to become a nun, huh? "South of the Border" was the song that taught Sinatra you could swing somewhat hokey scenarios and still produce something musically expressive and emotionally satisfying without taking things too seriously. Sinatra scholar Will Friedwald calls this part of the oeuvre a kind of "hard-swingin' heterosexual camp", which is as good as any other categorization. The record was released as "Frank Sinatra with Billy May & his Orchestra", got to Number Two, and set the singer up for all those other east-and-south-of-the-border things he would do with the real Billy May in the years ahead – "Granada", "Moonlight on the Ganges" and Jimmy Kennedy's own "Isle of Capri", which, arrangement-wise, is very much a sequel to "South of the Border".

It was a roomful of eminent musicians that day, a lot of whom – Sy Zentner, Pete Candoli, Tommy Peters – had worked with Billy May, and were convinced they were playing a new May chart. So who actually did that non-Billy May arrangement in the Billy May style? Well, it was a fellow called Nelson Riddle. And that April 30th 1953 session marked the first time Sinatra and Riddle had been in the studio together. "I got all the credit, but Nelson did all the work," said a rueful Billy May. But why would an already successful arranger ghost anonymously for some other fellow?

"He wanted to be there," said Frank's trombonist Milt Bernhart. That's to say, if this was his only shot at working with Sinatra, he'd take it. And how. Aside from "South of the Border", that April 30th session turned out to be most consequential, for Nelson and for Frank.

It worked out for Jimmy Kennedy, too. As his son JJ Kennedy wrote, "My father said that Sinatra put a lot of bounce into the song, giving it the zip that most of the other versions did not."

"And I think it needed it," said his dad. "Frank's up-tempo version gave it a terrific fillip and I don't think it has ever looked back since then. And it was all due to Frank."

The Fifties was a good time for second-time-arounds in the Kennedy catalogue. Aside from Sinatra's "South of the Border" and "Isle of Capri", Nat Cole revived "Red Sails in the Sunset" and the Platters had a big hit with "My Prayer". Jimmy Kennedy isn't exactly a household name, but he has the distinction of being the most successful British songwriter in America before Lennon & McCartney. Until the Beatles came along, Britain's pop industry was a small parochial thing reeling under a barrage of Yank imports, over-played, over-sexed and over here. The composers' professional body, the Performing Right Society, even called for severe protectionist measures, under which American songs could only have been played as part of an elaborate transatlantic-exchange musical-quota system, which would have been very economically disadvantageous to the Old Country once the Fab Four, the Stones, Elton John et al came along. Yet, for three decades in the mid-century heyday of the American standard song, Jimmy Kennedy was the British Isles' one-man exception that proved the general rule.

As for Michael Carr, I never met him, but every old Denmark Streeter tells stories about him – including the one about how, broke as usual, he went to see his publisher one Friday afternoon in hopes of a fifty-quid advance to tide him over till Monday. As was his wont, he collapsed on the floor in reception and professed to be dying, and gasped through ever slower breaths from the carpet that his final wish was to see Jimmy Phillips one last time.

"You've got the wrong office," said Bill Martin (later the writer of the England 1970 World Cup Squad's UK Number One hit "Back Home" and the Bay City Rollers' US Number One hit "Saturday Night"). "This is Cyril Gee's office. Jimmy's office is next door."

Carr stood up, dusted himself off, went next door, and fell on the carpet all over again. He composed a couple of instrumental hits for the Shadows, and in 1968 wrote a blockbuster hit for "Jacky" - the great Jackie Lee, who sang back-up vocals for everyone from Engelbert Humperdinck, on "Release Me", to Jimi Hendrix, on "Hey, Joe". She's also Irish, by the way - from Clontarf, on the northside of Dublin. Carr's hit for Jacky was "White Horses", the theme to a TV show that was the delight of every pony-loving schoolgirl for season after season:

When Jacky's single of "White Horses" entered the Top Ten, Michael Carr sent her a congratulatory telegram:

Thanks to you and White Horses I've now paid 3 years outstanding rent. Love Michael Carr

He didn't have to worry about back rent for long. A couple of months later, he collapsed on the floor, this time for real. The chancer was all out of chances, and he'd never need a couple of fivers for the pub again.

Just for a tender while

I kissed the smile

Upon her face

For it was fiesta

And we were so gay...

Happy one hundredth to Northern Ireland – or, as Keely Smith cheerily concludes, "Olé, you muthas":

~If you're in the mood for something more obviously shamrock-hued on this consequential Irish anniversary, Mark tells the story behind "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling" in his book A Song For The Season, available from the Steyn store. And, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter your promotional code at checkout for special member pricing.

If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Paul Simon, Alan Bergman, Lulu, Ted Nugent, Artie Shaw, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Tim Rice, Robert Davi and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is a special production of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and we also have a special Gift Membership.