Over the summer months, film columnist Rick McGinnis will be taking over SteynOnline's Saturday night movie date in a new series, Rick's Flicks, starting this evening.

Nobody can say that Miracle Mile set the world on fire – off screen, at least – when it was released in the spring of 1989. This little romance about the end of the world debuted at the Toronto film festival the previous fall, where I might have seen it for the first time, and barely made back a third of its tiny budget in theatres. Subsequent world events made the whole premise of the film as dated as a Patrick Nagel painting, and that should have been it for Miracle Mile.

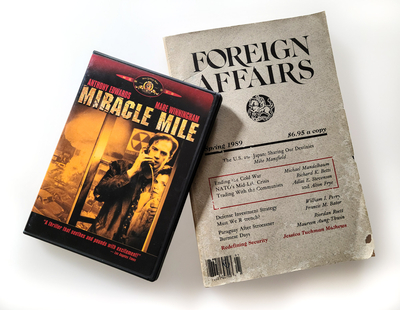

But it wasn't. At some point during the decade-long "End of History" before 9/11, director Steve De Jarnatt's movie developed a cult following, earning it first a terrible "formatted for your television" DVD release in 2003, and then a deluxe Blu-ray version in 2015. Pretty good for a movie with an infamously bleak ending that (screw spoiler alerts – this movie is over thirty years old) spares literally no one we've met during its brisk 90-minute runtime.

De Jarnatt's script for Miracle Mile spent nearly a decade as one of the most celebrated unproduced screenplays in Hollywood. In his long struggle to get it made, he actually took the fee he got not to direct Strange Brew (the producers decided they wanted to make the Bob and Doug McKenzie movie a Canadian production after De Jarnatt had signed a contract) and bought his story back from Warner Bros. The script was supposed to be the Twilight Zone film that ended up being made as an anthology, and infamously cost the lives of Hollywood veteran Vic Morrow and two child actors when a helicopter stunt went wrong during filming.

Kurt Russell and Nicholas Cage were each briefly considered as the leading man, but the role went to Anthony Edwards, still hot from Top Gun and before his fame grew and his hairline receded on the hit TV hospital drama ER. Mare Winningham, the plain girl in the Brat Pack, was cast as the female lead and given an unfortunate hairstyle that was popular with Junior A hockey league players from northern Ontario. Even at the time Winningham's hedgehog mullet was regarded with disbelief, and time has not been kinder.

Edwards plays Harry, a trombone player in a swing band – a young fogey who admits that he's burning through the last of his youth playing Glenn Miller impersonator. He meet-cutes Winningham's Julie at the natural history museum adjacent to L.A.'s La Brea Tar Pits, at the beginning of a marathon day-long first date where they release restaurant lobsters off the Santa Monica Pier and meet her estranged grandparents (one of whom is played by John Agar, ex-husband of Shirley Temple and John Wayne's co-star in John Ford's Fort Apache and She Wore A Yellow Ribbon.)

Harry, we learn, is a hapless victim of the chance nature of the universe. After dropping off Julie at her job waitressing at Johnie's – a diner on Wilshire Boulevard's Miracle Mile, and a minor masterpiece of midcentury "Googie" architecture – he goes back to his hotel for a nap. His discarded cigarette is taken by a pigeon to their nest, setting it ablaze and shorting out the hotel power, turning off Harry's alarm clock. He wakes up in the middle of the night, realizes that he's blown Julie off by nearly four hours, and heads to Johnie's to see if he can make amends.

Chance deals Harry another card when the pay phone outside the diner rings while he buys a newspaper. It's a wrong number – a young soldier at a missile silo in North Dakota who thought he was calling his dad in Orange County. They're locked down and ready to "shoot our wad," with the Soviet response due in just over an hour. The young soldier says they've seen him; there's a volley of gunfire and another voice telling Harry to forget what he's heard and "go back to sleep."

Back in the diner Harry wrestles with those instructions before deciding to tell everyone in the oddball late night crowd what he's heard. Nobody believes him until Landa, a well-connected yuppie (Denise Crosby, a star after one season on Star Trek: The Next Generation) who "used to date someone who worked for the Rand Corporation" corroborates his scant facts with her brick-sized mobile phone. They flee the diner, most of them intent on joining Landa's hasty plan to join the rumoured evacuation of bigwigs for Antarctica, starting at the helipad on the roof of the Mutual Benefit Life Building just across Wilshire, next to the tar pits.

On paper it sounds flimsy, but it's a testament to Edwards' performance, a cast loaded with great character actors, Tangerine Dream's relentless soundtrack and De Jarnatt's direction that it works – at least for this Gen Xer, born two years after the Cuban Missile Crisis. But it's hard to understand how primed we were with a simmering terror of nuclear war if you have no adult memories that begin before the release of Nevermind.

Miracle Mile came out at the end of three decades thick with cold war movies and nuclear apocalypse cinema. Stanley Kramer's star-studded but bleak 1959 movie version of Neville Shute's novel On The Beach is probably when it crawled from the b-movie underbrush, though for my generation it really begins in 1964 with Stanley Kubrick's black comedy Dr. Strangelove and its po-faced doppelganger, Sidney Lumet's Fail Safe. After that the genre went from military thrillers like The Bedford Incident (1965) and Twilight's Last Gleaming (1977) to eccentricities like The Bed Sitting Room (1968) and A Boy and His Dog (1975). The bomb was a running plot device in most James Bond films, as well as the Planet of the Apes series and the Godzilla franchise.

But it was a cluster of theatrical and TV movies like Testament, The Day After, WarGames, Red Dawn, Countdown to Looking Glass, Special Bulletin and Threads in 1983 and 1984 that set the tone for the decade. This was when De Jarnatt was writing and re-writing his script, and it shows – the Cold War was at its hottest since the Cuban Missile Crisis then, with Soviet misinterpretation of the Able Archer NATO training exercise in 1983 very nearly setting off a missile exchange. The bomb was all over art films like Andrei Tarkovsky's The Sacrifice (1987) as well as the animated feature When The Wind Blows (1986) and even anime such as Barefoot Gen (1983) and Grave of the Fireflies (1988).

I had seen most of these films without really trying, and you would assume that Harry and Julie and nearly everyone in Johnie's had seen them as well. After the panic a lunging attempt at survival begins, down scenarios everyone had watched, read or imagined over and over. The Atomic Cafe, a satirical 1982 documentary about civil defense propaganda, had been a cult hit on the rep cinema circuit, and put the final nail in our delusions about "duck and cover" or survival in the wake of Mutually Assured Destruction. ("Seriously, man – M.A.D. It's really called that, I'm not shitting you. I read it somewhere.")

I know I'm not the only kid who sat around with friends placidly debating where you'd rather be – in a bomb shelter or right at ground zero. Most boys agreed that ground zero was the best choice, but only if you were there with the prettiest girl at school, for one last (or first, probably) shot at fulfilling your biological imperative before being atomized. I'm not sure I knew if any girl ever shared this fantasy.

Harry goes into survival mode, beginning a picaresque trip through night time L.A. on his way to get Julie, slumbering under the influence of a Valium in her grandmother's Park La Brea apartment. After finding her he loses her again while looking for a helicopter pilot, finds her and then loses her again after a stand-off with a SWAT team. All along the way his story about the imminent end causes panic and casualties. By dawn Harry's story has percolated through the whole city, leading to a traffic jam and a riot on Wilshire where the bodies literally start piling up around Harry as he crawls along the pavement.

With no confirmation of the US attack or a Soviet response, Harry worries that he might have been nothing more than a Chicken Little, responsible for the breakdown of society. Julie's grandparents seem wiser: they reconcile and turn down the escape to Antarctica, opting to head to Cantor's Deli and ride out the end of the world together quietly with a fatty corned beef sandwich. They might have found shelter there with members of Guns N' Roses, who hung out at Cantor's in the late '80s waiting for their big break. In retrospect, nuclear winter actually doesn't seem a steep price to pay if it prevents near constant airplay of "Sweet Child of Mine."

Harry finds Julie again in the lobby of the Mutual Life Benefit Building, and in the agonizingly slow elevator ride up to the helipad they realize that they might not make it. "It's the insects' turn now," Harry says, before they scramble to exercise their biological imperative on the floor of the lift.

But the elevator door opens on an empty helipad. The first missile soars overhead toward Tijuana. The helicopter returns and takes off with Harry and Julie just as more missiles fly over Vendenberg Air Force Base, Hines Peak and Santa Clarita. An EMP takes out the chopper's controls and they spiral down – into the La Brea tar pits, where the movie started. As the chopper sinks, Harry tells Julie that maybe they'll find them there one day, along with all the other fossils preserved in the tar, or maybe the heat from a direct hit will turn them into diamonds. The screen turns black and then blooms to white with the sound of the last warhead's arrival.

A downer ending, and one I thought wholly probable at the time, but what did I know? As Miracle Mile hit the theatres the venerable foreign policy journal Foreign Affairs published a Cold War-themed issue. I was a regular reader and I still have it. The ads inside are for books with titles like Crisis Stability and Nuclear War, March to Armageddon, Retreat From Doomsday, A Strategy for Peace, Moving Targets: Nuclear Strategy and National Security, and Next Moves: An Arms Control Agenda for the 1990s, which was being heavily hyped to the wonks, academics and journalists who regularly read think tank-funded quarterlies like Foreign Affairs.

One of the trio of featured articles is "Trading With the Communists," co-written by Adlai Stevenson III, son of the man who was beaten by Eisenhower twice, an example of Foreign Affairs demurely broadcasting the dinner conversation of our political elites. The lead feature is "Ending the Cold War" by Michael Mandelbaum, "Director of the Project on East-West Relations" and a senior fellow of the Council on Foreign Relations, publisher of Foreign Affairs.

Things were looking cautiously hopeful in Mikhail Gorbachev's USSR, writes Mandelbaum, and provided the hardliners didn't dethrone him in a party putsch, we might never have another close call like Able Archer. It will remain, he assures us, a bipartite world, even if the Soviet Union tentatively withdraws from its empire in Eastern Europe and the developing world to focus on internal stability.

"The Soviet Union will not, in the foreseeable future, become a Western-Style country, with a capitalist economy with several competing parties," Mandelbaum writes, and he wasn't totally wrong. His conclusion, however, was not prescient: "The ending of the Cold War is a process, not an event. Thus the conflict will not end with either a bang or a whimper. It will probably not end in a way that can be readily noticed."

That summer, Hungary opened its border with Austria. Within weeks Czechoslovakia let refugees cross its border into Hungary. East Germany began talking about letting citizens cross into West Germany, then accidentally made it happen with a miscommunication by East Berlin's party leader. On the 9th of November people poured through border checkpoints, then started taking sledgehammers to the Berlin Wall. The Romanians shot their dictator and his wife on Christmas Day. The Warsaw Pact voted itself out of existence in February of 1991; the Soviet Union dissolved itself the day after Christmas the same year.

If you were alive then, you definitely noticed.

The Soviet Union might be gone and the Cold War history but the Bomb is still here – in real life, and in movies, where it remains a threat in the hands of terrorists, neo-Nazis and rogue Russian generals in countless Clancy-esque thrillers. The apocalypse also lingers, as a result of stray meteors and alien invasions and climate catastrophe, though the special effects that can portray the end so spectacularly these days mostly prompts a kind of mellow nostalgia for Boomers and Xers who imagined it so many times before; the end might look so much more convincing onscreen, but it sure isn't any scarier.

I saw the same nuclear nostalgia in my fellow Xers who made conspicuous plans to retreat off-grid to cabins and cottages when Y2K loomed. After rehearsing the Big One in their minds for so long, they weren't going to squander this long-delayed chance to bug out. When history got back into full gear with 9/11, though, we were unprepared. Neither our imaginations nor the movies had prepared us for it.

When the Cold War ended I had to confront the idea of living beyond thirty. Doom was no longer a condition to love, and all the people who had started real lives in defiance of the apocalypse no longer looked so naive. I'll admit it: the Cold War arrested my development. A friend once asked to borrow my DVD of Miracle Mile after I called it the most romantic film I ever saw. She returned it saying that it made her sad and depressed, and worried about my whole worldview. Nobody who knows me would doubt this story.

De Jarnatt never made anything as interesting as Miracle Mile. He's moved back home to Washington state where he tends to the reputation of his film. In a Hollywood Reporter story about the 30th anniversary of its release, he said the only regret he had was Winningham's hair. "That will haunt me, and I guess audiences, forever. I guess it puts you in the '80s. It seemed like a good idea."

The world – at least as I write this – did not end. Johnie's Coffee Shop was the L.A. campaign headquarters of the 2016 Bernie Sanders campaign. The lawn in front of what was once the Mutual Benefit Life Building now contains several sections of the Berlin Wall. The best outcome of Miracle Mile was for Anthony Edwards and Mare Winningham, who remained friends for years after making the film, but became a couple after working on bonus material for the Blu-ray reissue. And then there's the rest of us, who weren't incinerated in a fireball or didn't waste away from radiation sickness during nuclear winter. If you look at it that way, Miracle Mile really did have a happy ending.

This column is here because my dear friend, Kathy Shaidle, is no longer around to write it. I won't pretend that I can be as confrontational, acute, fearless or funny as Kathy, but knowing that she wanted me to step into this space I'm going to try my best. Everyone who knew Kathy as a friend or a reader misses her; there's still a daily pain when I realize that I won't hear her unerring take on some news story or cultural off-gassing. She left an enormous void when she left, and everything I hope to write into that space is dedicated to her memory.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Rick know what they think by logging in and sharing in the comments below. Access to the comments section is one of many benefits that comes along with membership in the Mark Steyn Club. Kick back with your fellow Club members in person aboard our third Mark Steyn Cruise, featuring Michele Bachmann, John O'Sullivan, Conrad Black and Mark himself, among others.