It was the Academy Awards last Sunday, and not only did I fail to acknowledge them, I wasn't even aware they were taking place; Not only had I not seen any of the nominated pictures, I hadn't even heard of them. I'm a cautious fellow when it comes to cultural ignorance: I remember as a child my father's declining interest in the Oscars, from still being interested in that year's movies to tuning in mainly for the lifetime-achievement awards to total indifference even to the lifetime honorees. Yet, in my case, the complete lack of interest is at least borne out by the data: This was the most unwatched Oscars ever, with about ten million viewers - or about thrice what a certain Canadian guest-host pulls on an average "Tucker Carlson Tonight".

Which meant we were at least spared all those pious self-inflating homilies about "a billion people watching around the planet" agog for the winner of Best Animated Short.

The musical contributions are what concern us in this department, of course. This year the winner was "Fight for You" from Judas and the Black Messiah. If you say so. But for about half its history the Academy Award for Best Original Song produced some of the best standards in the repertoire: We have celebrated them in this space, from the very first, "The Continental", via "The Way You Look Tonight" and "Over the Rainbow" to "Born Free", "Windmills of Your Mind" and "Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head", with steeply declining interest as we reach the winners of the last decade or so.

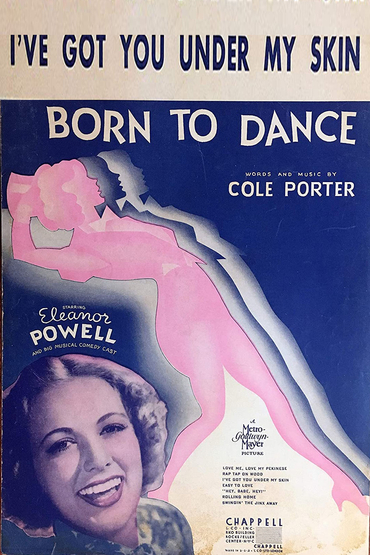

We have also featured some of the losers, because in its heyday the Best Song shut-outs were also great standards-in-embryo. Consider, for example, the third year of the category, for Best Original Song in a motion picture of 1936. "The Way You Look Tonight" won, but the mere nominees included "Pennies from Heaven" and "I've Got You Under My Skin": all three are among the highest rank of popular songwriter. If you're wondering about the company they were keeping, the remaining nominees were "A Melody from the Sky", which is not quite the celestial delight its title proclaims but is perfectly respectable, and "Did I Remember?", which makes for a very charming moment between Cary Grant and a somewhat put-out Jean Harlow in Suzy:

Of the three other losers I thought we'd spend a little time with a song that, like the lovely ballad it lost to, represents the heights of the catalogue. What follows includes material from Mark Steyn's American Songbook:

On January 12th 1956 Frank Sinatra walked into KHJ Studios in Los Angeles and recorded a Nelson Riddle arrangement of a Cole Porter song. Usually with Frank, he knew what he had to do and, as in his movies, he nailed it on the second take, or maybe the third or fourth. But that night it took 22 to get this particular song just right, and to that initial couple of dozen he added thousands more over the years. For four decades, in Vegas, New York, Tokyo, Paris, London, you'd hear the little vamping intro figure, and over it something like:

Oh, here's one we can't leave out. Cole Porter's shining hour and Nelson Riddle's great work...

And then the first line:

I've Got You Under My Skin...

Out of a zillion alternatives, here's Sinatra having a good time in the Dominican Republic, back in the Eighties:

Other songs came and went from the act ("Goody Goody", "Without A Song"); others went from ballad tempo to hard and swinging ("Where Or When", "The Song Is You") or underwent less obvious modifications ("You Make Me Feel So Young", "The Lady Is A Tramp"). But once he'd taken charge of that Nelson Riddle chart, he never changed it - from that January night in 1956 to the Duets version with a somewhat superfluous Bono wailing "Don't you know, ya ol' fool, you never can win?" forty years later.

"Under My Skin" was recorded for Songs For Swingin' Lovers, the first blockbuster album of the LP era. I was once in a restaurant with Frank's pal Sammy Cahn and after singing me a chunk of "Swingin' Down The Lane" he looked out at the room of middle-aged diners and mused, "Have you ever thought about how many of these people were conceived to Songs For Swingin' Lovers?" Yet, even by the standards of that smash album, "Under My Skin" is special. Nelson Riddle's work on the song may be the all-time great pop vocal arrangement, and certainly Milt Bernhart's 16-bar contribution is the most-heard trombone solo in recorded music:

To see the title on a track listing is to conjure an entire world – except perhaps on my 1980s Japanese import of Swingin' Lovers where it appears as "I've Got You Under My Sink", which sounds like a song for swingin' serial killers.

That misprint aside, when Riddle talked about scoring Frank in "the tempo of the heartbeat", this is what he had in mind: "I've Got You Under My Skin" is a landmark of the Sinatra style, the song that defines the persona – swagger and obsession, breeziness and vulnerability.

It didn't start out that way. Cole Porter wrote the song 20 years earlier, for a 1936 film called Born To Dance. Eleanor Powell and James Stewart starred, and Jimmy got to warble, very charmingly, the big ballad "Easy To Love". But "Under My Skin" went to the dance duo Georges and Jalna for a nightclub scene, and then afterwards on the sprawling penthouse terrace Virginia Bruce turns to Jimmy Stewart and sings for the first time:

I've Got You Under My Skin

I've got you deep in the heart of me...

And that's how the song was born. There was no verse, no second chorus. If you know the lyrics only from the Sinatra version, that's all there is: there's no little-known wittily rhymed additional Porter quatrains for the cognoscenti. And it doesn't need them: the song's fancy enough as it is. It's a beguine, as in Porter's "Begin The...", as in Broadway exotica: instead of thirty-two bars, it's fifty-six. And, instead of the usual four eight-bar phrases – main theme, re-stated, middle section, back to main theme, or AABA – if you try to break this song down into eight-bar phrases it comes in as A-B-A1-B1-C-D-A1½ – for whatever that's worth. The point is it's a complicated business, moving from its key of E flat into D minor, G dominant, C major, back to F minor, B-flat dominant, and home to E flat again. It's the sort of thing that could easily be too overwrought and precious to be any good. The great American musicologist Alec Wilder described it as full of "things which I tend to shy away from", including repeated notes, eight bars of triplets, and the kind of unnatural triple rhyme to which Porter was partial. In "Night and Day" it's "under the hide of me" and the "hungry yearning burning inside of me". In "Skin" it's:

Use your mentality

Wake up to reality...

Did Porter use his mentality when he came up with that couplet?

And yet the song is so great that, as Wilder conceded, "I must waive all my prejudices". It was nominated for an Oscar but lost to "The Way You Look Tonight". And over the next two decades ambitious jazzmen (Charlie Mingus) appreciated the tune and discriminating singers (Lee Wiley) picked up the number. I love Miss Wiley, even when, as here, she takes her time getting to the microphone:

It also enjoyed a cachet in certain circles as a coded gay song. But I'll bet it would have wound up as one of those tunes a little too special for its own good had Sinatra and Riddle not taken it into KHJ on January 12th 1956.

He'd never sung it before, but he'd come close. On his radio show in 1944, he did a little "tribute" to Born To Dance, acknowledging that most listeners had likely forgotten the picture, and then he sang "Easy To Love" in a shimmering Axel Stordahl arrangement and, halfway through, the choir come in and waltz their way through "I've Got You Under My Skin". Aside from a couple of lines in the middle, it's not a Sinatra performance of the song, but the song is part of a Sinatra performance:

Twelve years later, he had other plans for it. As always on his best work, he knew what he wanted, telling Nelson Riddle, "I want a long crescendo."

"I don't think he was aware," said Riddle, "of the way I was going to achieve that crescendo, but he wanted an instrumental interlude that would be exciting and carry the orchestra up and then come on down where he would finish out the arrangement vocally."

At that stage, Riddle wasn't aware of how he was going to achieve that crescendo either. He thought of Ravel's Bolero, which is the all-time great crescendo, all 15 minutes of it. "Now that's sex in music," Riddle liked to say. "Skin" was a last-minute addition to the January 12th session, and the arranger was running out of time. The Riddles recalled Mrs R driving to KHJ for the 8pm session with Nelson in the back still writing out the charts.

That could be true. Billy May wrote his marvelous taxi-down-the-runway-and-take-off arrangement of "Come Fly With Me" an hour before the session, and somewhat over-lubricated. But, whatever short shrift the other songs got, Riddle put a lot of thought into "Skin". "I remembered a Stan Kenton record, and that trombone back-and-forth thing" – Kenton's "23 Degrees North, 82 Degrees West":

That Kenton record gave Nelson Riddle the layout he wanted: the overlaid rhythm patterns building like a mega-intense Bolero to Milt Bernhart's trombone solo. He knew he had something special going. After the orchestral run-through, the band just sat there. And then they stood up and applauded. Riddle brushed the cigarette ash off his shirt and said, "Yeah, how about that?"

And so Sinatra arrived and did "It Happened In Monterey", one of those South-of-the-border-for-a-little-hey-hey numbers, and "Swingin' Down The Lane", a lovely evocative spooning song from the Twenties by Isham Jones and Gus Kahn, and "Flowers Mean Forgiveness", a filler for some single, and then they got to the main course. And, as it went to four and five and six takes, Sinatra began to see that he could hone and refine this thing without losing the spontaneity. He was the one who decided Milt Bernhart needed to be closer to the mike, so he could blow the roof off. But the mike was high on a riser and it was Frank himself who went out of the studio and found a box for Bernhart to stand on. By that twenty-second take, they had what they wanted. Frank's first chorus is intimate, reflective:

I tried so not to give in

I said to myself this affair

Never will go so well...

And then comes the controlled pressure-building burn of Riddle's crescendo. If you saw Sinatra live over the years, you'll know that, as it built, he liked to bark, "Run for cover! Run and hide!" And then Bernhart explodes with a solo of what Will Friedwald, the great analyst of Sinatra's work, calls "atavistic off-the-chord energy". And, as wild as that is, the singer comes back for the release and makes the obsession even more frenzied:

Don't you know, little fool?

You never can win...

But sometimes you can. Sinatra stuck with Riddle's arrangement for Sinatra's Sinatra in 1963 and Duets in 1993 and on all the concert albums – Live In Australia (1959), Live In Paris (1962), At The Sands (1966), The Main Event (1974) and the Eighties Vegas set. Sinatra and Riddle had taken a piece of Broadway exotica and stripped it of its fripperies. And, in normalizing it, they enhanced it: reconstructed in straight four/four, it emerges as the apotheosis of the Cole Porter songbook, a glorious combination of passion and rhythm.

It was one of those arrangements that supplanted the song – Oscar Peterson's piano instrumental is, in effect, the Sinatra record pared down; singers from Steve Lawrence to Michael Bublé have recorded "Skin" in Frank's arrangement; even Carly Simon's bland trudge through the number is a reorchestration of the Riddle chart with all the life sapped out of it. I'm not a great fan of Diana Krall but at least when she did the song she slowed it down and found her own take on it:

Sinatra departed from the Riddle version only a couple of times over the next 40 years. In 1967, he took part in an inaugural discussion at the University of Southern California's Cole Porter Library. Garson Kanin was the moderator and the participants included Fred Astaire, Gene Kelly, Alan Jay Lerner, Ethel Merman and Jimmy Stewart. Frank recalled his days singing at the Rustic Cabin, a New Jersey roadhouse, and being so stunned when Porter swung by one evening that he forgot all the words to the song. In honor of Porter and the academic venue, Sinatra was being very respectful that evening and delivered a gorgeous version of "It's Alright With Me" and then, accompanied only by pianist Roger Edens (from the old MGM music department), a slow, intimate, ravishing "I've Got You Under My Skin".

Artie Shaw once asked me, rhetorically, how we know Mozart's any good. Because he's lasted. When a piece of classical music endures 200 years, we know it has value. As Shaw pointed out, his records still sound good after 60 years, which isn't bad for something as ephemeral as pop music. The Sinatra-Riddle-Bernhart record of "Under My Skin" will still be heard in another six decades, and most every night between now and then at some joint somewhere or other some wannabe-Frank will be singing that arrangement or his approximation thereof, hoping to deflect just a little of its sheen his way. If you ever saw Frank Sinatra on stage, chances are, right at the end of the song, you heard him direct this question at some gal in the crowd:

Where does it hurt you, baby?

And then the answer:

Under my skin.

~The above includes material from Mark Steyn's American Songbook, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore.

If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Paul Simon, Alan Bergman, Lulu, Ted Nugent, Artie Shaw, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Tim Rice, Robert Davi and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is a special production of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and we also have a special Gift Membership.