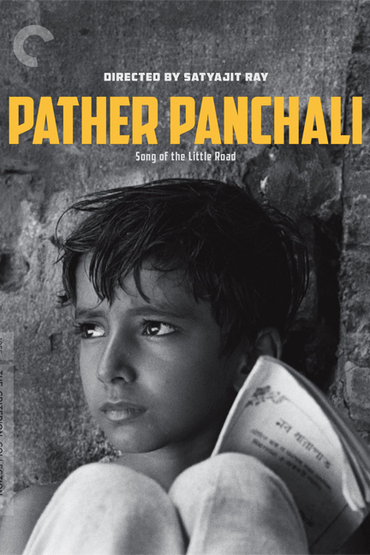

Tomorrow, Sunday, is the centenary of Satyajit Ray, novelist, publisher, illustrator, composer, lyricist ...and above all a great film-maker. Ray was born on May 2nd 1921 in Calcutta in the Bengal Presidency of British India. On what would have been his hundredth birhday, we present our late friend Kathy Shaidle's take on his 1955 classic Pather Panchali:

"Not to have seen the cinema of Satyajit Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon." – Akira Kurosawa

When Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali debuted at the 1955 Cannes Film Festival, no less a personage than Francois Truffaut stomped out early, declaiming, "I don't want to see a movie about peasants eating with their hands."

He wasn't on the jury that year, though. Pather Panchali won — not the Palme D'Or, the Grande Prix or even the Special Jury Prize (Cannes' "Miss Congeniality") — but the "Most Human Document" award, which (as its off-key, by-committee moniker attests) the jury cooked up on the fly.

And has never handed out since.

Such are the paradoxes of Pather Panchali:

Perennially lauded as one of the greatest films ever made by Sight & Sound and Time Out, its director wasn't a "director" at all. Ray, a Calcutta graphic artist and cinephile, had imbibed 99 European films during a business trip to London. De Sica's neorealist Bicycle Thieves impressed him most; he resolved to somehow make a similar movie, one made in and about India, but stringently stripped of Bollywood's already formulaic wacky dance numbers, overripe colour and manic histrionics. Ray's Pather Panchali "cinematographer" had never operated a movie camera before the first day of shooting. His "actors" (but for one) were amateurs.

Basically, Satyajit Ray was Ed Wood, but with talent.

Or rather, instinct. Except that isn't right, either.

The trouble with talking about Pather Panchali is that, well, you have to use words...

Here's the easiest part:

Pather Panchali is a slice of one family's life, set in rural India circa 1910. The father, an itinerant poet-priest, nurtures fantasies of success which (we realize during his first scene — WATCH) will never materialize. His wife (need I add the adjective "long suffering"?) is mostly left alone to raise their two children: impish little Apu and his enigmatic older sister Durga, by turns caring and careless. Rounding out the household is the inevitable "aunty," a toothless old woman so withered and bent she resembles (barely) ambulatory driftwood.

Apu and Durga play and fight and grow, and Mother and Aunty squabble and perform their repetitious, quotidian chores, in and around their broken-down home in the midst of what might as well be a jungle. Their neighbours are relatively better off (even in their poverty), and delight in rubbing that in.

At this point, some of you may be thinking that Truffaut guy might've been onto something...

I first watched Pather Panchali on TCM last May, merely to discharge a "see before you die" duty. This film — with its unpronounceable title and director, its nobody cast and beyond-foreign, unglamorous milieu — had been sandwiched between Citizen Kane and The Rules of the Game on every "great movies" list I'd ever seen. So damnitall, I was gonna sit through it, however penitentially.

Especially since TCM was airing Criterion's painstaking restoration, performed twenty years after the film's original negatives were charred in a freak fire.

Just five minutes in (WATCH), I was poised to bail. But I'd experienced that identical sensation at the start of another highly regarded movie, The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943), which is now one of my absolute touchstones.

So as Pather Panchali inched along at its caterpillar pace, I resolved not to reach for the remote.

Two hours later...

Back to my struggle for words.

It may help to focus on (an, alas, unrestored clip of) Pather Panchali's iconic set piece. (Don't be put off — the Criterion edition looks like a newly minted nickel):

Durga leads Apu far from the village, to show him something he's only heard rumors about. They sometimes run, sometimes meander, across field after field after field. No sooner have they stopped to rest at last than they hear the thing approach, at a heavy-breathing gallop — then pass them by as quickly as it came:

A director like Fellini would have to be physically restrained from stencilling "SYMBOL" on that train's engine. And indeed, critics claim the train in Pather Panchali represents Modernity or Hope or The (God help me) Partition of India or any number of Capitalized Words.

These critics must have watched a different movie. Because I do not believe that, any more than I believe the snake in the film symbolizes Doom or the dead frog splayed on its back after the monsoon symbolizes, er, Death.

Pather Panchali, almost alone in the annals of "art cinema," is devoid of symbols.

The train is a train. The monsoon, an unfortunate climactic commonplace in that particular part of the world. Snakes do not slither through the ruins of houses on cue, to thoughtfully ornament our personal tragedies. Frogs die.

And so do people. There are two deaths in Pather Panchali, one expected, one not. By the time the latter occurred, and the devastating penultimate scene had come and gone (and I realized I'd forgotten, for who knows how long, to breathe) I'd been bewitched by the film's uncommon lack of guile, its still-revolutionary ability to inspire authentic empathy and awe without resorting to the manipulative "cue the orchestra!" movie trickery of either "-wood," be it "Bolly-" or "Holly-."

Think of its roughest Hollywood equivalent, 1940's The Grapes of Wrath: An outright propaganda piece, based on a balderdash novel, its "look" lifted from Dorthea Lange photos (which were posed, by the way, and worse, its impoverished subjects uncompensated.)

Whereas Pather Panchali has no message, no politics. It is not an outrage delivery mechanism, cynically crafted to Change the World (Or Else).

Rather, like its train and its jungle, its umbrellas and cows, Pather Panchali is elemental, The Thing Itself. Its title translates into Song of the Little Road, but I will always think of it as being Bengali for, simply:

This.

The next morning, the burden on my heart was still there, the one I'd tried to wish away when I'd turned off the TV and pulled up the covers. I rarely recall my dreams for more than a split second after I wake up, but I remember, still, that I'd dreamt of Pather Panchali.

Maybe you will too.

~If you are missing, as we all are, our pal Kathy Shaidle, do check out our new Shaidle at the Cinema home page for the full archive of her work: It's a grand collection of the best writing on films and film-makers.

If you're a member of The Mark Steyn Club, do please share your view of our movie feature in the comments section. If you're not a member of The Mark Steyn Club, we're fast approaching our fourth birthday and would love to welcome you to our ranks.