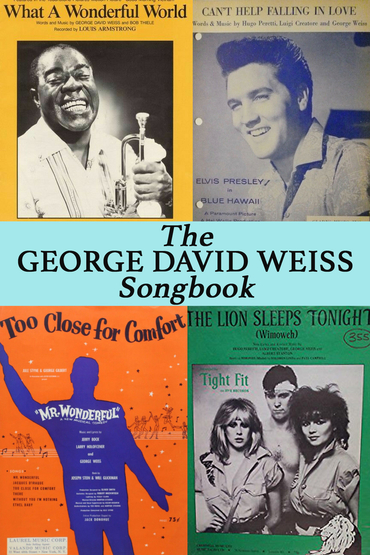

This weekend marks the centenary of George David Weiss, born April 9th 1921. Who was George David Weiss? Well, he's no household name, but, to reprise my old line on obscure songwriters, you'd be hard put to find a household that doesn't know at least one George David Weiss song. Here's how he started: This was his first Number One record, three-quarters of a century ago - January 1946 - with Frankie Carle and his orchestra, with vocalist Marjorie Hughes:

...and this was his last chart-topper - a UK Number One in 1982 for (gulp) Tight Fit:

Oops, no, wait - six years later, this was Number One in Australia in 1988:

Well, okay, forget the Number One revivals, what was the last new song of his to make the Hit Parade? George David Weiss started out as an arranger for Stan Kenton and Vincent Lopez, and thirty years later was doing Philadelphia soul hits that went Top Ten for the Stylistics:

Oh, okay, a couple more. Here's George David Weiss as rendered by the Andrews Sisters and Les Paul:

And here is George David Weiss as rendered by Whitesnake:

I do believe that's the first time we've played Whitesnake in fifteen years of Steyn's Song of the Week, and it will be at least another fifteen years before we play them again, so make the most of it.

So who was George David Weiss? Well, even George Shearing, who wrote his one and only enduring song with Weiss, had no more to say about him in his autobiography than that he was "a man by the name of George David Weiss". The man by the name of was born under that name in April 1921 and was all set to become a lawyer or accountant when he decided to follow his heart and go to Juilliard, where he learned composing and arranging. The latter got him employment with Stan Kenton and other bands, until he met his first songwriting partner, the talented West Indian composer Bennie Benjamin. A young Sinatra picked up their "Oh, What It Seemed to Be", and a few years later Kay Starr had a monster hit with "Wheel of Fortune":

By 1950, Weiss was arranging charts for big bands and scoring movies, and sometimes he wrote words to other men's tunes, and sometimes he wrote tunes for other men's words, and sometimes he did a bit of crafty re-purposing, as with "Can't Help Falling in Love", which derives from "Plaisir d'Amour", composed by Jean-Paul-Égide Martini in 1784:

Being George David Weiss is different from being Cole Porter or Irving Berlin, but it's a rare talent, and in demand. Back in late 1948, the British pianist George Shearing had a residency at the Clique Club on Broadway and 44th Street. The following year the club changed hands and the new owner, Morris Levy, decided to rename it after Charlie "Bird" Parker. It wasn't much of an honor: The room was nothing special, just another little New York jazz joint that at capacity held maybe 150, 175 customers. But three years later Levy came to an arrangement with the radio station WJZ to host a nightly show from Birdland. Not live music, just a disc-jockey spinning platters from 11pm into the small hours. But Levy figured it would help to have a theme tune, which would be played every hour on the hour. So he had one rustled up and asked George Shearing to record it.

There was a small problem. Shearing didn't like the tune. "Look, I can't relate very well to this theme you've sent me," he told Levy. "Why don't I write one for you?"

As one wily businessman to another, the club owner figured the pianist was working his own little angle into Levy's deal. "I'll bet you'd like to write one," he said. "Because you have your own music publishing company, haven't you?"

Shearing insisted it was entirely for artistic reasons. He couldn't record a theme for the club unless "I can feel comfortable about playing it."

"Well," said Levy, thinking of his own comfort levels, "we would feel comfortable about you playing a tune that we own."

So Shearing agreed that he'd get the composing rights but Levy would get the publishing rights. Mrs Shearing was none too happy about the arrangement, because at the time she was running George's publishing company and she didn't like the idea of losing out on the publishing royalties. She cheered up when she heard his new tune because it was so bad she was pretty confident there'd be no royalties to lose. "That's terrible," Trixie told her husband.

Shearing agreed. But as much as he wrestled with the assignment he couldn't come up with anything better. So after a few days he stuck it in the mail and sent it to Levy. That evening, in the middle of eating his char-broiled steak at their home in Old Tappan, New Jersey, he suddenly jumped up from the table. "What's wrong now?" said the missus. Shearing had been known to leap from his chair when presented with a meal not to his taste. This time, though, he ran to the piano, sat down, began to play, and ten minutes later had the whole of "Lullaby Of Birdland" mapped out. At the end, he turned to Trixie: "What do you think of that?"

"I went back to that butcher many times," he told me years later, "but I never got a steak that did the trick again."

Shearing told Levy to forget the first tune, and sent him the new one. It was a late night radio show from Birdland so they called the theme "Lullaby of Birdland". The show and the tune did well - so well that acts booked into the club quickly began including the theme as a tip of the hat. In 1953, a year after its composition, the Count Basie Orchestra was playing Birdland and delivered a performance of Shearing's tune that's as great as any in the years since. But the number's fame spread way beyond the club: If you were at Massey Hall in Toronto in '53, you could have heard Bud Powell play it with Charlie Mingus and Max Roach.

And then Morris Levy got to thinking: What's more lucrative than a hit tune? A hit song. So he turned to, as we noted above, "a man by the name of George David Weiss".

As we've had cause to remark on several previous occasions, the trouble with putting words to an existing jazz instrumental is that it tends to come out sounding less like a song than as an instrumental somebody's singing a lyric to. It lacks the unity of a conceived song. In Weiss' case, he was additionally handicapped by the pre-existing title: "Lullaby of Birdland". What would such a lyric be about? The club? Charlie Parker? A land of especial ornithological significance? In the end, Weiss decided to write basic boy-meets-girl and shoehorn the title in as necessary. So:

Lullaby Of Birdland

That's what I

Always hear

When you sigh...

Okay, what next? Weiss then decides to rhyme the title:

Never in my wordland

Could there be ways

To reveal

In a phrase

How I feel...

"Never in my wordland"? We're in I-can't-believe-what-I've-just-heardland! When I bashed the tune out as a child, I assumed "wordland" was some sort of hepcat talk - a popular vernacular term beatniks used as a synonym for "vocabulary" or "dictionary". But, of course, Weiss just pulled it out of the air, and then has to justify it with a sideways rewrite of "You're just too marvelous, Too Marvelous For Words". What's odd is that the obtrusive Larry Hart-like Ira Gershwinesque coinage of "wordland" is plunked in the middle of otherwise entirely conventional love-song language and imagery. It's not even clear Weiss needed to rhyme it. In fact, on the equivalent lines in the next section, he dispenses with rhyme altogether:

Have you ever heard two

Turtle doves

Bill and coo

When they love?

That's the kind of magic

Music we make with our lips

When we kiss...

Weiss isn't the most punctilious of lyricists - the plural "doves" is paired with a singular "love", and it's never very clear whether "lips" and "kiss" is a bad rhyme or meant to be unrhymed. "Turtle doves" is presumably an attempt to conjure a vision of Birdland that doesn't depend on the listener being an habitué of Manhattan nightclubs. So Weiss tries to extend the thought: Birds. What do birds do? They sit in trees. Maybe there's a bisyllabic tree that would fit the middle section:

And there's a weepy ol' willow

He really knows how to cry

That's how I'd cry in my pillow

If you should tell me

Farewell and goodbye...

But, if the tune's great, a lyric only has to be good enough. Weiss' words fit the notes and sing easily. They do the job. On my battered bit of sheet music, I see the song is credited to "George Shearing and B Y Forster". That's because, of America's two music licensing agencies, Shearing was a member of BMI and Weiss a member of Ascap, and in those days it was not permitted for an Ascap writer to collaborate with a BMI writer. Hence, the pseudonym. "We wrote a half-Ascap song," as the punning Shearing liked to say. Here he is with Peggy Lee on the Bing Crosby show:

No disrespect to Mr Weiss' English lyric, but on the radio years ago I loved to play this record, by the Polynesians singing in their native tongue:

In 1956, a couple of years after "Lullaby of Birdland", George David Weiss found himself with a hit musical on Broadway - not a blockbuster like Guys and Dolls or The King and I or Gypsy or The Music Man or My Fair Lady or any of the other runaway smashes in a decade that played like one glorious season, as Alan Jay Lerner described it to me; but just a show that had a respectable run and made a profit. Mister Wonderful was an underplotted vehicle for Sammy Davis Jr with a score by Weiss, Larry Holofcener and Jerry Bock. Mr Bock would later team up with Sheldon Harnick for Fiddler on the Roof, which made him a "Broadway composer" in a way that Weiss never quite became.

But they did get two hits out of Mister Wonderful. One was Sam's big number "Too Close for Comfort", which is a cracking song disfigured at its climax by the lazy non-rhyme "One thing leads to another/Too late to run for cover": "Another" does not lead to "cover", and that grim pairing itself is reason to run for cover. I believe it is Mr Holofcener who is responsible for it. Sammy Davis kept the song in his act for years and perversely chose to play up the bum rhyme. Nevertheless, this later record with Marty Paich conducting is quite something:

The other hit from Mister Wonderful was the title song, which I generally find a rather bland ballad. However, I always associate it with my father who liked to sing it as he was shaving in the morning just to perk himself up and kickstart the day. So, whenever I hear the thing, I see my late dad standing in front of the shaving mirror singing the song to himself and concluding:

Mister Wonderful

That's me...

Here's Peggy Lee in 1982 with the original lyric - and a rather more intimate arrangement than on her record a quarter-century earlier:

That was the same year Tight Fit got to Number One in the UK with "The Lion Sleeps Tonight". If you don't recall Tight Fit, well, the bottom inevitably drops out of the Tight Fits of the music biz. But "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" roars on regardless. It's one of the biggest songs ever about a lion, apart from the Oscar-winning "Born Free" and the Eagles' "You can't hide those lion eyes". "The Lion Sleeps Tonight" has been a hit in every medium - on movie screens all over the world, in Disney's The Lion King, and then on Broadway, in the stage version. Before Tight Fit, it was a Billboard Number Three for Robert John in the Seventies, a Number One for the Tokens in the Sixties...

As you may recall, we've written before about the kleptocrat Commie Pete Seeger's appropriation of a South African tune called "Mbube" by Solomon Linda. Seeger knew exactly what he was doing, but he got away with it for many years, as we've recorded. Nonetheless, and unaware of Seeger's theft, a decade after Seeger had had the tune credited to him as "Paul Campbell", George David Weiss wrote those famous words about the mighty jungle and a dozy panthera leo.

That was the brief. In 1961, the Tokens, a group from Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, turned up to audition for the producers Hugo & Luigi (Hugo Peretti and Luigi Creatore) at RCA and sang "Wimoweh", a beloved staple of the Weavers, the Kingston Trio and other luminaries of the folk boom. And it was fine, but Hugo & Luigi were in the market for something a little less folkie and turned to their pal George Weiss to see if he'd be interested in turning it into a more or less regular pop song. Weiss didn't much care for the guys a-hootin' an' a-hollerin' "A-wimoweh a-wimoweh" bar after bar like a bunch of buttondown Brooklynite tribesmen, but an eight-bar instrumental phrase at the end of all the zeudo-Zulu chanting tickled his fancy. So he moved it up and made it the melodic center of the song and then figured out what the lyric ought to be about. The Tokens had mentioned to Huge and Luge (as they called their pop biz honchos in those pre-Trump non-Yuge days) that the South African consulate had told them the the song was something to do with a lion. Okay, thought Weiss. So it's a song about a lion. What's the lion doing? Not much:

In the jungle, the mighty jungle

The Lion Sleeps Tonight...

The lyric's a masterful way of taking what's really little more than a wonderfully catchy hook and using it to hint at a whole world. After that first phrase, Weiss mulled it over and for the next couplet added one new adjective:

In the jungle, the quiet jungle

The Lion Sleeps Tonight...

Okay, now what? Well, who else is in the neighborhood?

Near the village, the peaceful village

The Lion Sleeps Tonight...

And how about we reprise the hit adjective from the previous verselet?

Near the village, the quiet village

The Lion Sleeps Tonight...

And then Weiss hints at just a wee bit of potential drama:

Hush, my darling, don't fear, my darling

The Lion Sleeps Tonight...

And that's pretty much it. Sixty-two words, or (excluding repetitions) 16 words. I can't improve on the brilliant analysis by Ilonka David-Biluska, who was briefly a Continental vedette in the Sixties and billed as "The Voice of South Africa", despite her Hungarian name. Invited by EMI in Amsterdam to sing the Dutch version of the song, Ilonka wasn't impressed:

I looked at the lyrics and my heart sank. Apart from a prodigious number of 'Wimowehs', there were only three lines. I shall paraphrase: a lion is sleeping in a mighty but quiet jungle, near a peaceful and quiet village and a darling, presumably somewhere in a hut in the village, is told to hush and not to fear because the lion is asleep tonight. The Dutch translation, according to the sheet music (which was later published with my photograph on the cover) left out the fearful darling and noted merely that the jungle was big, the village small and the night dark. Oh yes, the lion was still asleep.

I refused to sing it.

Back in New York, the Tokens did as they were told but resented it. "We were embarrassed," said Phil Margo, "and tried to convince Hugo & Luigi not to release it. They said it would be a big record and it was going out." It did:

It had an orchestra, a trio of Tokens doing the wimoweh-ing, Jay Siegal's falsetto, an opera singer with a spare half-hour who came in and did a bit of contrapuntal ululating. The first time the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson heard it he had to pull off the road he was so overawed. Carole King declared the record a bona fide "motherf***er".

Hard to argue with that - and by the guy who did "Wheel of Fortune" and "Mister Wonderful".

On the other hand, if you're not the kind of chap in the market for a bona fide motherf***er, you may prefer, as I do, this ballad, written by Weiss and Joe Sherman. Here's Nat King Cole on the BBC in 1963 with the Cliff Adams Singers (of Sing Something Simple fame). Just lovely:

That "Go on, kiss her/Go on and kiss her" isn't flashy or clever and it looks like nothing on paper. But, as a marriage of words and music, it's songwriting at its best.

Another terrific George Weiss record from the mid-Sixties owes its existence to Sinatra canceling a recording session at short notice. With a 46-piece orchestra already booked, Warners offered the date to Jerry ("Time Is on My Side") Ragovoy. Like almost everyone else in town, he'd written a song with Weiss. He'd had in mind Lorraine Ellison to sing it. Now all he had to do was rustle up a 46-piece orchestral arrangement in nothing flat:

In 1981 The Book of Rock Lists pronounced the above "the best female vocal ever". As Joey of the Ramones remarked, "I would've stayed."

No centennial appreciation of George David Weiss would be complete without a song that didn't seem a big deal at the time, especially in America, where the performer's management and record company and whatnot all loathed it. But around the planet, and eventually in the US too, it became an anthem, to the point where my kid and his school pals chose it as their class song for Eighth Grade graduation. It was pretty bloody terrible, I have to say. By the end, the gym had been drained of every last iota of buoyant high-school-here-we-come eager anticipation that had filled the room only three minutes earlier. Don't worry, I'm not telling tales literally out of school: I'd warned them in advance to stick to something more Eighth Gradey, like "Put on a Happy Face". This one, in the wrong hands, can turn pretty dirge-like pretty quickly.

It started with Bob Thiele, who was a successful record producer but only a very occasional songwriter. So, for a composing partner, he turned, as so many others have done, to George David Weiss. In theory the latter could have written any or all of "What a Wonderful World", but Thiele told me that Weiss stayed mostly down the musical end.

Which I find hard to believe, because the tune is mostly "Twinkle, twinkle, little star" and, after decades in the music biz, Weiss was way beyond that.

On the other hand, Weiss told Graham Nash (of the Hollies and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young) that he wrote it with Louis Armstrong in mind - which suggests he also had a hand in the lyric.

Why Satchmo? Well, it was a ballad of hope and optimism that transcended the times. But for that very reason it also required a singer who transcended the times.

A singer like, say, Louis Armstrong...

And, if you think that seems kind of obvious now, it certainly wasn't in 1967. If you pick up almost any jazz critic's biography of Satchmo, they generally follow the same basic arc: Terrific trumpeter, innovative musician - and then he sold out and did commercial pap for suburban hi-fi filler. I don't subscribe to that crude reductio myself, but it is true that, after he'd booted the Beatles off the top and taken "Hello, Dolly!" to Number One, the calculus changed somewhat for Armstrong's management: There's a new Broadway show opening? Take the big song and do another "Dolly" knock-off. Hence Satchmo's "Mame" and Satchmo's "Cabaret", and doubtless, had he lived, Satchmo's "Jesus Christ Superstar" and Satchmo's "Phantom of the Opera". (You can hear Jerry Herman talk about his bewilderment at Pops' success with "Dolly" here.)

Nevertheless, the writers met with Louis to pitch the song. As Bob Thiele recalled, "We wanted this immortal musician and performer to say, as only he could, the world really is great: full of the love and sharing people make possible for themselves and each other every day."

Instead, Satch peered at the sheet - unlike many singers, he was a musician who could read the music - and, when his eye got to the bottom of the page, he looked up and said:

What is this sh*t?

He was studying the music - no words, just a contemporary ballad tune that called not for Armstrong's tight jazzy All-Stars but for a string section willing to play "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star". I wouldn't myself say the tune was exactly "sh*t". From the C# passing tone under the first chord, it has an harmonic subtlety that lends a conditional quality to the title: it's a hope that this can be kept "A Wonderful World" rather than a ringing declaration thereof.

But, as I said, Armstrong hadn't seen the lyrics. And, when they passed him the words, he fell in love. Not so much because of the green trees, red roses, blue skies, white clouds, but because of the final eight bars, which ditch the "colors of the rainbow" theme:

I hear babies cry, I watch them grow

They'll learn much more than I'll never know

And I think to myself

What A Wonderful World...

That quatrain reminded him of 107th Street in Queens, the tree-lined block he and his wife Lucille had lived on for a quarter-century (and whose modest red-brick home now houses the Louis Armstrong Museum):

There's so much in 'Wonderful World' that brings me back to my neighborhood where I live in Corona, New York. Lucille and I, ever since we're married, we've been right there in that block. And everybody keeps their little homes up like we do and it's just like one big family. I saw three generations come up on that block. And they're all with their children, grandchildren, they come back to see Uncle Satchmo and Aunt Lucille ...and I got pictures of them when they was five, six and seven years old. So when they hand me this 'Wonderful World,' I didn't look no further, that was it.

He was genuinely touched by the heartfelt optimistic simplicity of the sentiment, and its faith in the future - that a new generation would know things that he would never live to see. Like, er, Twitter. Well, let's not get hung up on the details. He was struck by the song's message, and so agreed to sing it.

An arrangement was made, musicians were booked, and a studio was procured - for a midnight session in Vegas, after Satch had finished up his set at the Tropicana. There was just one problem. Louis Armstrong had recently switched record labels, to ABC, and the president of the company, Larry Newton, was opposed to Satchmo doing "What a Wonderful World". I don't mean he was antipathetic or indifferent to it, or felt it was not a strong choice for a single but would be okay for Side 2 Track 5 of an album. I don't even mean that he disliked it. He loathed "What a Wonderful World" with a passion: He thought he'd signed the Number One bestselling pop star of "Hello, Dolly!", and he didn't want his new act doing what he regarded as the polar opposite of "Dolly" - a soporific inert crawl-tempo ballad.

He's not necessarily mistaken about that, as my kid's class certainly demonstrated. So I'm not unsympathetic to Larry Newton's concerns. The trouble was that on August 16th 1967 he'd flown in to Vegas for a photo shoot with his new star and that evening he showed up at United Studios determined to prevent the recording. He went so totally bananas that Ed Thiele, as producer, and Artie Butler, the arranger, and George Weiss and Frank Military, who were also present, hustled him through the door and locked him out of the studio. Which isn't exactly conducive to Louis Armstrong recording a tender and sensitive ballad unlike anything he'd sung before:

I hear label presidents cry, outside the door

He should be back minding the store

And I think to myself

Why'd I sign with this guy?

It was a long session - either because of Newton's antics or because they were interrupted by the toots of passing Union Pacific freight trains, or because the material was a little outside Pops' comfort zone. They stayed there till 6am, and then they all went for breakfast. And the label only agreed to pay the orchestra for their extended shift on condition that Satchmo himself accept a mere $250 for the session. But it was worth it: Louis worked and worked on his interpretation until he and the writers were satisfied. I confess as a young child I always heard "the dark sacred night" as "the dark say goodnight", but once I'd grasped Satch's enunciation I appreciated what a fine pairing that makes with "the bright blessed day": it adds a subtle touch of the holy and transcendental to the song; that the world is not merely "wonderful" in the way that a great cheeseburger and a vanilla shake can be, but truly wonderful because it's the wonder of God's creation. But, as I said, it's discreetly done. And Armstrong's reading of the middle-eight, in that unmistakeable beautiful gravelly rasp, is as sincere and true as anything he ever sang:

The colors of the rainbow, so pretty in the sky

Are also on the faces of people going by

I see friends shaking hands, saying 'How do you do?'

They're really saying, 'I love you...'

Is that really what they're saying? Well, Pops bought into it. In the studio that night, representing all those children who'd grow to learn more than he'd ever know, was George Weiss' kid Peggy. "So you're George's daughter? Pleased to meet you!" And he shook her hand, and maybe, for a small, shrunken old man not in the best of health, it really did mean "I love you."

On television, Satch was even more enthusiastic, prefacing his performance with these words:

Seems to me, it ain't the world that's so bad but what we're doin' to it. And all I'm saying is, see, what a wonderful world it would be if only we'd give it a chance. Love, baby, love! That's the secret, yeah. If lots more of us loved each other, we'd solve lots more problems. And then this world would be a gasser!

And, for those wondering what the hell all this hippie-dippie peace'n'love stuff had to do with Louis Armstrong, he waited to the very end to tie it back to his entire oeuvre in what, with hindsight, was the only possible wrap-up:

Ohhhhhh, yeahhhhhh.

Larry Newton wanted another "Hello, Dolly!" Well, he got the last two words.

But he wasn't happy, and he swore to exact his revenge - by doubling down on the petty and stupid. In order to prove he was right about the song, he released the single in late 1967, but refused to promote it. He didn't ship it to radio stations, so no disc-jockeys played it, and nobody bought it. In those days, ABC's UK distribution was licensed to EMI, and, in the fullness of time, "What a Wonderful World" showed up at the London office, and they released it as a normal single. Actually, not that normal, because it was, I believe, the very last single EMI released on their HMV label. But, other than that, they did all the things you're meant to do with a new release: They sent review copies to the BBC and to trade magazines, and discovered what Larry Newton, once he'd gotten over being locked out of the studio, should have realized - that people really liked it. It entered the UK charts at the beginning of February 1968 at Number 45, cracked the Top Forty in its second week, the Top Thirty in its fourth, and then climbed through March and April up to Number One.

So, just for the record, where did it get to on the Billboard Hot 100?

Er, big hit sound Number 116.

In fact, Larry Newton's singular talent for sabotage was so effective that he wound up with a record that was a hit everywhere except his own territory: Top Thirty in Australia, Top Twenty in New Zealand and the Netherlands, Number Seven in Switzerland, Number Six in Belgium and Germany and Norway, Number Two in Ireland, Number One in Austria... What a wonderful world (America excepted). In London, EMI decided the song was so big they needed an album built around it. At which point Larry Newton decided to triple-down on the moronic. He agreed to the LP, but only if Armstrong did it for $500. Joe Glaser, Louis' manager, wasn't in the mood for that, and instructed Bob Thiele:

You tell that fat bastard to go f**k himself and give us $25,000 for eight more sides.

Larry Newton responded:

Tell him to go f**k himself, and why do we give a sh*t about these European companies? Screw 'em all.

They're really saying "I love you".

George Weiss and Bob Thiele wrote Pops a follow-up: "Hello, Brother", a slightly hokey paean to the working joe who just wants a fair shake. But lightning rarely strikes twice, and that's as it should be:

We've been so chock-a-block with George David Weiss hits, we had to include one of the flops. For any jobbing songwriter has far more "Hello, Brothers" than "The Lion Sleeps Tonights".

Three years later, Louis Armstrong was dead. If you'd been listening to the radio in Britain, Europe, around the planet in 1971, they marked his passing with "What a Wonderful World". On American stations, they played everything but.

It took two decades and Good Morning, Vietnam for a great record finally to achieve the recognition on its home turf it had known for a generation everywhere else. It doesn't matter that Satch was born in 1901; he sounds old and elegaic on the record, and that's the point: he's a fellow approaching the end of his life, but he's not bitter or even bittersweet; he's not looking back but looking forward to when those babies will grow. It's an old man, but it's a young song. That's why it's a popular father/daughter dance at weddings: It's the past blessing the future.

And that's also true of any great songwriter's catalogue - which is why we salute George David Weiss on his centennial.

As for Larry Newton, well, I wasn't sure whether he was still with us or not, so I looked him up, and read:

Newton is probably best remembered today for trying to stop Louis Armstrong from recording 'What A Wonderful World'.

Ohhhhhh, yeahhhhhh!

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Paul Simon, Alan Bergman, Lulu, Ted Nugent, Artie Shaw, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Tim Rice and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and we also have a special Gift Membership.