Programming note: Later this evening Mark will begin a brand new Tale for Our Time. We hope you'll join him.

Seventy years ago, April 1951, this famous record began a two-month run at Number One on the Billboard charts:

That perfect little pop single still sounds great seven decades later, but we're not about records in this department, we're about songs. And there are so many records of that song that it's one of the most performed and recorded songs of all time: You can get it in country, pop, and a zillion jazz instrumentals. Anything left? Disco maybe? Nah, too late; been there, done that:

How faint the tune? Not this one. It's not only one of the most performed and recorded songs of all time, it's the most performed and recorded song to be written by a woman.

So who would that be?

Well, not my favorite female lyricist, Dorothy Fields, nor my second favorite, Carolyn Leigh, but rather ...Nancy Hamilton.

Who?

Well, I knew Miss Hamilton a little in her final years (Ann Ronell, composer of "Willow Weep for Me", did the introductions). She was born on July 27th 1908 at Sewickley, Pennsylvania, and studied in Paris at the Sorbonne. Young Nancy was a wit with a stage presence, and, after a few college shows, made her debut on Broadway in a 1934 revue called New Faces. Among the new faces were Imogene Coca and Henry Fonda, but the best material went to Nancy Hamilton, who, aside from acting in the show, also co-produced and wrote most of the sketches. She gave a wicked parody of Katherine Hepburn in The Little Woman, and she demonstrated how the big pop hits of the day might sound if they fell into the hands of Walt Disney's Three Little Pigs.

If you're wondering why Hank Fonda and Imogene Coca were the ones who went on to screen success, well, you can get a kinda sorta hint in the way the gentlemen of the press wrote up young Miss Hamilton, dwelling on the "faint touch of severity in her get-up, her sleek, boyish haircut, dark tailored clothes, navy-blue beret." For The New York Post, Wambly Bald filed a profile headlined "Bachelor Girl Makes Good on Broadway": He described Nancy as a "big-boned woman who stands five feet seven inches with her shoes off. Her weight is 145 pounds, neatly distributed beneath her dark tailored suit. And she has short, crisp hair."

Ah, there's that "sleek, boyish" hair again. Which wasn't the only boyish thing about her. Wambly Bald emphasized that, like hardboiled male writers for the pulps, she had "a habit of sipping beer while at the typewriter... she also likes to work in the garden, rolling up her sleeves for some real physical effort, such as digging in the earth or whitewashing the fence..."

Anything else? Oh, yeah: "She hates shopping."

Gee, it's almost like they're trying to tell us something.

By the time I met her, Nancy Hamilton was well known, at least in theatrical circles, as the relict of the late Katherine Cornell, the soi-disant "First Lady of the American Stage": for much of her life, Nancy had been the First Lady's first lady.

As to her songwriting, my late friend Ned Sherrin, in his book Song by Song, devotes precisely one sentence to Miss Hamilton's achievements:

Nancy Hamilton contributed principally to revues: 'A Lovely, Lazy Kind of Day' is perhaps her best-known song.

If you say so, Ned. I can't recall ever hearing "Lovely, Lazy Kind of Day" played on the radio, and I'd bet you couldn't find one person in a million who knows it. But I'd wager a solid majority of the remaining 999,999 would have a nodding acquaintance with "How High the Moon".

Is Miss Hamilton's status as a one-hit songwriter due to deeply ingrained mid-twentieth-century music-biz prejudice against members of the lesbian community? I don't think so. Aside from not being terribly interested in men, Nancy wasn't terribly interested in music. She had a glib, facile wit that could compass the world around her, see the comedy in it, and then calculate whether the joke was best expressed in a sketch, a sight gag, or an amusing verse. Five years after New Faces of 1934, she came up with One for the Money, which she conceived and produced and wrote the sketches and lyrics for. In the wake of the smash-hit left-wing revue Pins and Needles, she mocked the plonking earnestness of left-wing agitprop; the show opens with bloated plutocrats in evening dress quaffing champagne and declaring, "We think right is right and wrong is left." There followed some sport at the expense of boy genius Orson Welles, who is said to have known Shakespeare backward at two, forward at three, and personally at four.

Nancy's composing partner on all her shows was a chap called Morgan Lewis, born in Rockville, Connecticut on December 26th 1906. Miss Hamilton's wit dazzled, and Mr Lewis was content to serve her dazzle. Over the years, he wrote hundreds of tunes to show off her funny rhymes and larky characters, and, if there was anything of great melodic or harmonic inventiveness in the music, she doesn't appear to have noticed it. Thus, the entire Hamilton & Lewis songbook made little impact outside the theatre.

Except, that is, for one spectacular entry.

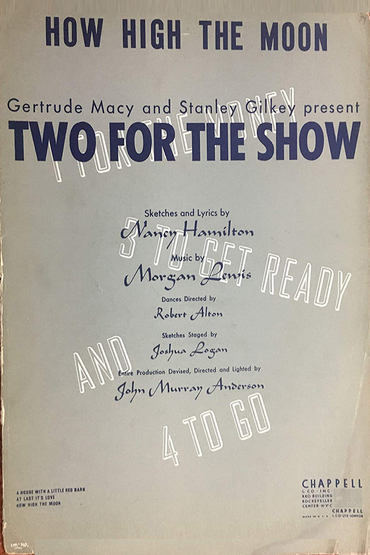

The year after One for the Money, the pair wrote a sequel called Two for the Show. It opened in August 1940, fifteen months after One for the Money closed, but another world: Much of the planet, if not yet America, was now at war. And Nancy Hamilton knew enough about the theatre to know that, even in revue, you have to vary the diet and pause the non-stop yukfest for something true and sincere. So she set a scene in London during the Blitz: The all-clear siren sounds in Belgrave Square, the lights begin to come on, and various couples drift outdoors. Frances Comstock and Alfred Drake sing a slow dreamy romantic ballad:

Somewhere there's music

How faint the tune

Somewhere there's heaven

How High The moon...

And then two couples dance to the tune - until the lights go out again as another siren sounds, and another air raid begins:

The darkest night would shine

If you would come to me soon

Until you will

How still my heart

How High The Moon.

Nobody made cast albums of the Hamilton & Lewis shows, because the songs had very little life outside the theatre. But I would like to have seen and heard the company that introduced "How High the Moon". Alfred Drake went on to a long career as a Broadway leading man in Oklahoma!, Kiss Me, Kate, Kismet; he played Benedict in Much Ado About Nothing opposite Katherine Hepburn. I telephoned him once to hunt down some information about an old Vernon Duke score I was attempting to unearth for a BBC project, and he was very helpful, so, while I had him on the line, I thought I'd ask him about "How High the Moon". He replied very coolly, "If you don't mind, I think I'll return to my life." So, whether he thought I'd been given an inch and was taking a mile, or whether his experience on Two for the Show had been unhappy and he had no wish to recall it, I shall never know.

Still, this was not like other Hamilton & Lewis revue songs. It should have been a big wartime ballad, like "I'll Be Seeing You". But the closest it ever got to that was a record made on the very day the show opened - August 8th 1940 - by Mitchell Ayres and his Fashions in Music, with vocal refrain by Mary Ann Mercer:

That was the second recording of "How High the Moon". But it was the first, made the preceding day by Benny Goodman with Helen Forrest, that was to set the song's course for the future:

As that Eddie Sauter arrangement was the first ever so tentatively to suggest, you really just want to forget about all that parted-couples-in-the-London Blitz stuff, and swing the hell out of an incredible tune. I was told years ago that Goodman's guitarist Charlie Christian was the chap who took "How High the Moon" from that April 1940 recording session and introduced it to the Harlem after-hours be-bop jam sessions: as the virologists would say, he was Patient Zero.

But, once it's in the air, it's easy to catch: This ostensibly simple song on a touching, sentimental, wartime theme is built on the most remarkable harmonic sequences. In thirteen bars it travels away from its parent key of G major and takes ten changes to work its way back - G minor, C dominant seventh, F major, F minor, B-flat-dominant seventh, E-flat major, C minor, D-dominant seventh, G minor, C-minor sixth ...and back to G major. That's red meat to a jazz improvisor - and no one wants to do it a t crawl tempo. So "How High the Moon" spent its first decade getting faster. Here's Al Casey and his Sextet in 1945:

And a few years on here's Dizzy Gillespie:

By now "How High the Moon" was the most performed song in jazz, and the soi-disant National Anthem of Bop. How did Nancy Hamilton feel about all this? Well, she certainly benefited from it: By 1949, a decade after she wrote the song, ASCAP, the performing rights organization, had moved her up into its top, highest-earning category of songwriters - ie, the same league as Cole Porter and Richard Rodgers - but, unlike them and their catalogues without end, she did entirely on the basis of one song. Nan Hamilton became a top-rank lyricist with a solitary blockbuster whose words, pre-Les Paul & Mary Ford, were ever more rarely sung.

If Miss Hamilton and Morgan Lewis were befuddled by all this, they knew enough not to chase the moon. Instead, they just went back to doing what they'd always done: amusing songs you forgot about as soon as you left the theatre. One for the Money and Two for the Show were followed in 1946 by Three to Make Ready. The cast including an unknown actor/singer called Gordon MacRae, and the sketches included "Kenosha Canoe", a parody of the new style of integrated "musical play", demonstrating how Theodore Dreiser's American Tragedy might sound if adapted by Rodgers & Hammerstein. Among the songs was that aforementioned classic, "A Lovely, Lazy Kind Of Day". Hamilton & Lewis also tried their hand at a book musical, about a man who does his bit for the war effort by selling phoney maps to Japanese spies. The show was called Count Me In. No reviewer distilled the public's reaction more pithily than John Mason Brown: "Count me out."

Yet no one ever said "count me out" to "How High the Moon", even as it got faster and faster, and further and further away from Belgrave Square during the Blitz. Morgan Lewis never wrote another hit, but then he didn't need to. Nor did Nancy Hamilton, and, notwithstanding the jazzers' affection for the harmonies of this song, it is a pleasing thought that the words are on one of the hoariest themes of Tin Pan Alley. For those smart alecks who like to sneer that pop lyrics are all "moon" and "June", it's not "Shine On Harvest Moon" nor "By The Light Of The Silv'ry Moon", but this song which is the most recorded "moon" song of all time.

Here's a lady who kept "How High the Moon" in her act till the end, singing Nancy Hamilton's words, after a fashion, in a famous performance in Berlin:

But here, in memory of two peripheral theatrical figures from the lost art of a revue, is the very same Ella with a very different "How High the Moon", complete with introductory verse:

I thank her for that.

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Paul Simon, Alan Bergman, Lulu, Ted Nugent, Artie Shaw, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Tim Rice and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and we also have a special Gift Membership.