Larry McMurtry died this past week, in the small town where he was born and spent almost all his life - Archer City, Texas, where his greatest film was partly shot. He was principally a novelist, but Hollywood came a-callin' early, turning his very first book into an effective vehicle for Paul Newman, Hud (1963). It wasn't long before McMurtry was being asked to do his own adaptations of his novels, and by the time of the telly version of Lonesome Dove he was a bona fide famous screenwriter. His blockbuster was Terms of Endearment (1983), which Kathy Shaidle wrote about for us here. His masterpiece was his very first screenplay, which I reviewed four years ago:

The Last Picture Show is set a long way from the glitter of Houston, in a northern town up near the Oklahoma border that does not show the state at its most appealing - a desolate, decrepit Main Street, tumbleweeds bowling down it, dusty pool hall, flimsy screen doors banging in the wind, you know the drill. It's a simply constructed tale on a familiar theme, following the final year of high school through to the dawn of adulthood. But I have always loved this film, since I first saw it when I was about the age of its protagonists, and it has stayed with me over the decades.

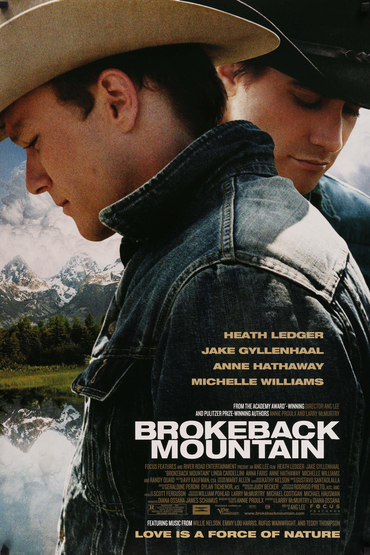

So, once you exclude Terms of Endearment and The Last Picture Show, what's left? Well, there's always the film for which he won an Oscar, a decade-and-a-half back, by which point he was an admired enough screenwriter that he was being asked to adapt not just his own work but that of others - in this case, a short story by Annie Proulx. Brokeback Mountain (2006) was touted as the first gay western:

"You know I ain't queer," Ennis Del Mar says to Jack Twist.

"Me neither," says Jack.

Then they get back to having sex with each other, high up in the hills of Wyoming.

I would have liked to have seen Brokeback Mountain with a Wyoming crowd, or at any rate an audience of rugged laconic men in tight jeans, such as Jack and Ennis. Unfortunately, it didn't appear to be playing in any rural districts other than, er, the Hamptons and Provincetown. So I had to go and see it in Montreal, where the author of the original story, Annie Proulx, once attended Sir George Williams University. The joint was packed, and you could have heard a pin drop when Jake Gyllenhaal's pants dropped.

But, other than in Montreal, it flopped. The film was supposed to be a provocation, and MSNBC and the rest of the gang blamed the "Christian right" for deliberately killing the movie by refusing to be provoked. Instead, the supposedly uptight right contented themselves with a few easygoing gags about the first western in which the good guys get it in the end. Which is funny, but not enough to get the mob stampeding the multiplexes. On the radio, Rush used it for one of his most memorable promos:

From the makers of Brokeback Mountain comes Return to Saddle-Sore Canyon: It's John McCain and Lindsey Graham as you've always wanted to see them!

Indeed. When Brokeback belly-flopped, it took Larry McMurtry's fitful movie career with it.

I confess I can't see what he saw in the story, other than the opportunity to virtue-signal all the way to an Academy Award. For what it's worth, I like Ms Proulx's books not because of the characters or the plots but because she's spent much of her life roaming the same turf I have — Vermont, Quebec, Newfoundland — and she's got a tremendous ability to capture the essence of the land, and in particular the way a harsh terrain shapes the character of its people. She began writing fiction in the Seventies, for Gray's Sporting Journal, which wanted hunting stories about men called Zack, and she co-founded a local newspaper in my part of the world called Behind the Times ("All the News That's Kept Till Now"), and in both she did a better job than most liberal progressive artsy types do of accepting country folk as they are. "I lean toward realism, not myth," she says.

But when you take a short story and make a movie of it realism turns all mythic. For a start, Jack Twist and Ennis Del Mar become two rising male stars, Gyllenhaal and Heath Ledger; you get a big orchestral score and tag lines on the posters ("Love Is a Force of Nature") and, though the Western literary tradition is not just Zane Grey and Bret Harte but also Willa Cather, when you put your fellows up on screen in cowboy hats on horses against the big sky of Wyoming, it looks far more like a crass and clumsy makeover of the manliest of Hollywood genres: Queer Eye for the Straight-Shootin' Guy.

Ang Lee's opening is very good: two young men who don't know each other wait outside a shabby trailer to be called in and offered a sheep-herding job, in the summer of '63. They say nothing, because they're from a culture where to be a man is to be taciturn. That's presumably why they went to Larry McMurtry: ever since Last Picture Show, he's been the go-to guy when you need dialogue for people who never say anything. So they stare into the distance, kick a little dust, lean against the truck, and steal an occasional glance at the other.

They don't really talk much for the rest of the movie. But one chilly night, alone up on Brokeback Mountain, in the early hours in a poky tent, something clicks. I'm no expert in gay seduction but I found this scene oddly unpersuasive: they go from opposite ends of the tent to penetrative sex in about six seconds.

Four years later, Ennis is a fitfully employed ranch-hand married to Alma (Michelle Williams, sweet and affecting as she was in those days) and they live above a laundromat with their two girls; and Jack is a tractor salesman down in Texas married to the boss's cowgirl daughter Lureen (Anne Hathaway) and the father of a little boy. They hook up again, and, as Jake gets out of the truck, they fall on each other hungrily in the shadow of the steps to Ennis's apartment.

And upstairs Alma happens to look down and see them kissing, and in one bewildered moment the assumptions of her life crack apart. The guys depart on a "fishing trip", the first of many over the years, from which Ennis never brings home any fish.

And from that point on the film settles down into not so much a "gay western" but a gay version of Same Time Next Year: the kids get older, the Sixties become the Seventies, Ennis divorces, Jack grows a moustache, but they still go up the hill thrice a year for "a couple of high-altitude f**ks", as he puts it. Which, to be honest, is a better summation of their relationship than "Love Is a Force of Nature".

In fact, across two-and-a-quarter hours, there's not a lot of evidence of "love", as opposed to a much-needed outlet. For its urban audiences, Brokeback is a new wrinkle on one of the oldest gay fantasies: the masculine man who likes sex with men. So it's a gay love story with ungaylike protagonists — Straight Eye for the Queer Guy. The rest of the time, in the distaff answer to lezzie porn for het men, for the gals it's a gabby chick flick with uncommunicative tough guys.

But by the end of a bleak portrait of failed lonely lives, with one of the lads cheating on the other with ranch-managers and Mexican rent boys, you're not even sure how gay-friendly the thing is: are the men selfish, uninterested parents because society's forced them to live a lie or because they're the sad self-destructive prisoners of their appetites? And, if it's such a "bold" "courageous" "groundbreaking" film, isn't it a little ridiculous that a gay male love story requires both Miss Richards and Miss Hathaway to bare their breasts with straight abandon while Messrs Ledger's and Gyllenhaal's penises never make it into shot? Instinctively, Ang Lee seems to understand that even this film's audience wants to keep some things closeted.

~You can find Mark's review of Larry McMurtry's Last Picture Show here - and Kathy Shaidle's review of McMurtry's Terms of Endearment here. Please do check out our new Shaidle at the Cinema home page for the full archive of our friend Kathy: It's a grand collection of the best writing on films and film-makers.

If you're a member of The Mark Steyn Club, then feel free to hit the comments. Do please be respectful to fellow commenters, and stay on topic.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's an Audio Book of the Month Club. It's also a discussion group of lively people around the world on the great questions of our time. It's a video poetry and live music club. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have an annual cruise. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we have a special Gift Membership. More details here.