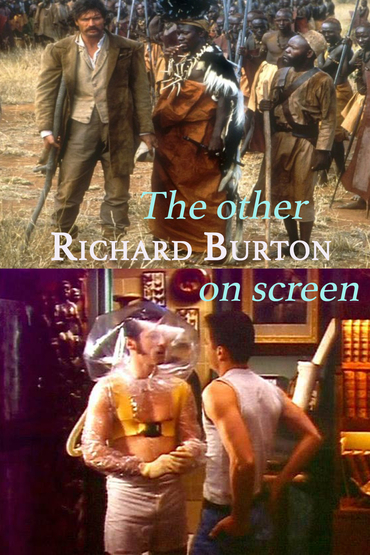

As noted on The Mark Steyn Show, this weekend marks the bicentennial of Richard Burton - no, not the bloke who married Elizabeth Taylor, but, as I said yesterday, the bloke who spent most of the nineteenth century warming up the name for the bloke who married Elizabeth Taylor. Oddly enough, the prototype Burton - explorer, linguist, swordsman, ethnologist, eroticist, translator of The Arabian Nights and The Kama Sutra - has also had a movie career of sorts. There are only two Burton pictures I know of, made within a couple of years of each other, but chalk and cheese. The first one is less weird, but not necessarily less fanciful. All they have in common is that both turn out to be about finding the source of things in Africa.

Bob Rafelson, whose catalogue includes Five Easy Pieces, Black Widow, The Postman Always Rings Twice and much else, directed the screen adaptation of William Harrison's "biographical novel", Burton and Speke. The names didn't mean much in Hollywood, so, by the time the picture was released in 1990, it had been retitled Mountains of the Moon. Which didn't mean much either. So the film got rave reviews from Roger Ebert and others - and flopped.

Which is a pity. Because it's quite a gripping account of one particular aspect of Burton's life - his and John Speke's attempts to find the headwaters of the Nile, and the toll it took on their friendship, such as it was. The massed ranks of British Equity are all in fine form - Bernard Hill as Dr Livingstone, Anna Massey and Leslie Phillips as Burton's in-laws, Richard E Grant as a duplicitous sh*t called Lowry (no, not that one), etc - and so is Omar Sharif as the local sultan who warns Burton and Speke about "Allah's terrible whimsy". Which is a good way of putting it, although these days even that line would be referred up to head office.

Fiona Shaw, who once told me on stage at the National Theatre that I looked like Tom Selleck (this was a long time ago, when Tom Selleck still looked like Tom Selleck) ...where was I? Oh, yeah: Fiona Shaw plays Isabel Arundell, who starts out as a fan and winds up as Burton's wife and, after a fashion, soul-mate. Tracing her naked form with a candle, the great man tells her, "You've made me forget all other women."

She's amused. "Your memory will return, I'm sure."

Not as much as you'd think. There's far less a-whorin' in the exotic east than you'd expect, and even the impressionable serving wenches of up-country African tribes get short shrift. "The things that haunt a man," explains a worldly village headman, are "a talkative woman, a mosquito, diarrhea" - which just about covers it, and Burton certainly takes the advice to heart.

As Richard Burton flicks go, the only problem is ...Richard Burton. Bob Rafelson seems to have decided that Sir Richard was basically an Irish chancer with a soft spot for the natives. We are told that the Royal Geographical Society and the like are opposed to him because he's "Irish" and, if the source of the Nile is to be discovered, better it be by a proper Englishman such as Speke. So Rafelson casts as Burton an actual Irishman, Patrick Bergin, speaking with an Irish brogue I doubt ever passed the real guy's lips: Richard Burton was born in Devon on March 21st 1821, baptized in Hertfordshire, schooled in Surrey, and divided the rest of his peripatetic youth between England, France and Italy, where he first learned to pick up the language and the girls. His father was a British Army officer born in Ireland to an Anglo-Irish family, but his mother's dad, for whom he was named, was an English squire. There are plenty of reasons why his contemporaries took a dislike to Burton - the whoring, the extraordinary eye for detail in his cataloguing of sexual practices, the enthusiasm for Islam, his participation in the Kama Shastra Society - but not whatever Rafelson means by his "Irishness".

This is a problem for two reasons. One, at least in the scenes set in England, turning Sir Richard Burton, KCMG, FRGS into a victim of Gaelophobia somehow makes him more ordinary. And two, Iain Glen plays Speke as a fellow who knows he's the straight man of the act, which is logical, but not when the film is in danger of turning into an act with two straight men.

In 1993, just three years after Mountains of the Moon, Sir Richard returned to the silver screen. He's not an Irishman this time, merely English - but he is working as a taxidermist in Toronto in the 1990s. If you're wondering how that happens, well, Zero Patience is a Canadian Aids musical. How about that? How often do you see a Canadian film musical? And how often do you see a Canadian film musical about a taxidermist? And how often does the taxidermist in the Canadian film musical turn out to be Sir Richard Burton?

It would be interesting to hear how John Greyson, writer/director of Zero Patience, came up with this fancy. But at the time he didn't seem awfully interested in the real Richard Burton and instead told interviewers things like: "Society has never been comfy with buttholes, especially queer buttholes." Even three decades back, this was a rather feeble provocation. I remember remarking that, au contraire, society seemed more comfy with queer buttholes than many queers: There was a BBC talk show hosted by Nick Ross on which, whenever Ian McKellen or some other dignified spokesgay turned up to call for amending legislation to permit pension benefits for same-sex partners or whatever, they'd immediately find themselves besieged by an extraordinary number of apparently expert listeners from Middle England - retired colonels and village spinsters - preoccupied by the tensile deficiencies of the rectal lining and other detailed rebuttals of details re buttholes.

All a long time ago, of course. Today being homosexual means moving to the suburbs and becoming deacons in your local Congregational Church while you raise more children than the straights bother having these days - all very butter wouldn't melt between your thighs. But John Greyson is old school. So the big duet in his musical is sung not by Sir Richard and his lover but by their respective bottoms.

Impressed as they were by the singing buttholes, critics nevertheless felt obliged to point out that a lot of the acting really wasn't terribly good. It fell to John Robinson to play Burton, and quite credibly given the circumstances. Sir Richard runs the "Hall of Contagion" at the Toronto Museum of Natural History and is looking for a centerpiece for his new exhibition. He alights on the subject of "Patient Zero" - Gaëtan Dugas, an Air Canada steward from Quebec who at the time had the dubious credit of having introduced Aids to North America. So, like Sir Richard, M Dugas emerges from the grave, and embarks on a kind of relationship with the great explorer.

Well, whatever. This sort of thing would go down better if the characters had any real life as opposed to being ciphers for points of view, regurgitating dialogue and song lyrics that are little more than facts and statistics. At its less dreary moments, it looks like a series of somewhat earnest public health announcements, perhaps of Scandinavian origin, designed to cheer up the afflicted: thus, an air stewardess on PWA (People With Aids) instructs her passengers in the "Empowerment Drill".

John Greyson, handicapped by a dull composer and mediocre cast, is hijacking the real Richard Burton for no other reason than to make a film opposed to what was then the prevailing Aids consensus. So Miss HIV, played by a Streisand drag queen, complains that, with no scientific evidence whatsoever, she's been fingered as the sole cause of the pandemic; an African green monkey sings about being blamed, with no proof, for spreading Aids to human beings; and, as for that alleged "Patient Zero", if he brought the disease to America, how come they've found people who died with Aids symptoms back in the Sixties?

And so I found myself thinking not about homosexuality or HIV, but about what's changed since 1993, which doesn't really seem that long ago. Back then you could make a film questioning public-health orthodoxy during a raging pandemic, and get raves from the critics, be nominated around the map, win "Best Canadian Film" and make the year-end Top Ten at The Dallas Observer. Less than three decades later, if you try to make a film - or even a song (Van Morrison) - questioning public-health orthodoxy during a raging pandemic, you'll be deplatformed within the hour and no-one will ever hear of it. Even though Doc Fauci in America and Professor Pantsdown in the UK are talking through their arses just as much as Richard Burton and Patient Zero in that butt duet.

Golly. I'm not sure how we wound up marking Sir Richard's bicentennial with warbling posteriors. But, if nothing else, it makes the point that somewhere out there there's still a really good Burton biopic waiting to be made.

~Please do check out our new Shaidle at the Cinema home page for the full archive of our peerless film essayist Kathy Shaidle: It's a grand collection of the best writing on films and film-makers.

If you're a member of The Mark Steyn Club, then feel free to hit the comments. Do please be respectful to fellow commenters, and stay on topic.

What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's an Audio Book of the Month Club. It's also a discussion group of lively people around the world on the great questions of our time. It's a video poetry and live music club. We don't (yet) have a clubhouse, but we do have an annual cruise. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, we have a special Gift Membership. More details here.