A few days ago on Sky News Down Under, I bade farewell to Chris Kenny with a poignant hope that I may yet set foot in the Lucky Country once more before I die. The odds of that seem to be worsening with each month of the Permanent Abnormal. So I hope you'll forgive me a wistful pining for where I was exactly half a decade ago - in the midst of my 2016 sellout tour of Australia. No opportunity for a 2017, 2018 or 2019 tour because loser cockwomble Cary Katz and his vanity TV network kept suing me to no avail. With Katz, Levin, Beck & Co vanquished, I was looking forward to setting my sails Southern Crosswards ...and at that point the ChiCom Lockdown hit. So in lieu of packing out Cloncurry I can only look back with a pang...

Five years ago, I was following a grueling schedule that kept my nose mostly to the grindstone. But I had promised myself that when we hit the Victoria leg of the tour that I would bust loose for a couple of hours and treat myself to a matinée of Georgy Girl: The Seekers Musical at Her Majesty's Theatre in Melbourne.

Victoria's capital is where the Seekers started out in folk clubs and coffee houses almost six decades back, of course, and the hometown crowd loved the show. The creators didn't make the mistake made by many jukebox musicals of over-complicating things, and it was a very winning cast. If it came out more as "The Judith Durham Story" than "The Seekers Story", perhaps that's the nature of the beast: even among the chaps' roles, her late husband and a straying English boyfriend were in dramatic terms the male leads while Athol, Keith and Bruce seemed at times to be relegated to the supporting cast. The dancing was excellent, which seems an odd thing to say about a Seekers musical, and parts of the Second Act were tragic and moving if a little undernourished in the set-up.

But I had two modest quibbles - about the treatment of two of the biggest songs, both of which I felt went a little under-exploited. One was "Georgy Girl" (which quibble I'll leave to another day), and the second was this week's Song of the Week. Ever since I'd landed in Oz and been informed the Seekers show was still playing, I'd been in a Seekerish mood, and the one I'd been warbling in the shower from Perth to Brisbane to Cloncurry and Mount Isa had been "Morningtown Ride", a child's lullaby that, at least for me, seems to take on deeper shades as the years roll by.

It was a smash for the Seekers, but in the show it wound up getting very short shrift. Judith is in hospital with appendicitis, and the lads gather round her bedside to sing:

Train whistle blowing

Makes a sleepy noise

Underneath their blankets

Go all the girls and boysRockin', rollin', ridin'

Out along the bay

All bound for Morningtown

Many miles away...

When Hal Prince revived Show Boat in the Nineties, I complained that he'd turned "Why Do I Love You?", a grown-up love song, into a children's song, for Elaine Stritch to sing to a newborn babe. "Morningtown Ride" is a children's song that certainly resonates for grown-ups, especially in the Seekers' wonderfully rich vocal blend - but not if it's a partial rendition, cut off by the narrator cynically remarking that the bedside scene never happened. It seemed a terrible waste of one of the most evocative of their hits.

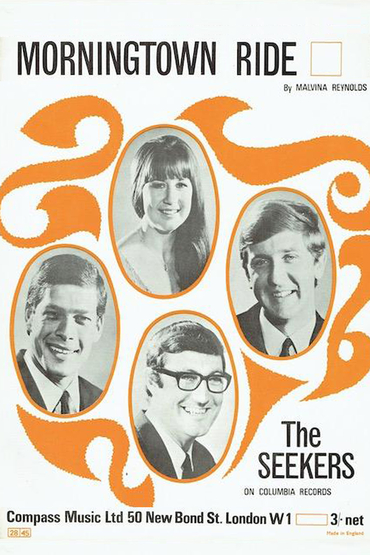

They first recorded it in 1964 for the grimly titled Hide & Seekers LP, with Bobby Richards' orchestra, and then two years on re-made it, with Tom Springfield producing. It hit Number Two in Britain - or one place higher than "Georgy Girl" would reach a couple of months later.

By then the song was almost a decade old. It was written in 1957 by Malvina Reynolds. When first her name caught my eye on a record sleeve many years ago, I assumed she was vaguely Hispanic - the Argentines like to call the Falkland Islands las Islas Malvinas, which President Obama, pandering to his Latin hosts a couple of years back, rendered as "the Maldives" (close enough). But Malvinas is an Hispanicization of the French name Îles Malouines, so called because the first Frenchman to stumble on them, Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, had set sail from St-Malo in Brittany. And so it turns out that "Malvina" is a Gaelic name - from mala mhinn, meaning "smooth brow", which the Scots poet James Macpherson transformed into a girl's name in the 18th century. Napoleon was a big fan of Macpherson's poetry, so the name became popular in Scandinavia, because Napoleon was a godfather to several children of King Carl XIV Johan of Sweden and King Carl III Johan of Norway - they're the same guy, but they had different numerals in each realm, as indeed I recall CJAD's Tommy Schnurmacher once suggesting Queen Elizabeth ought to have in Canada...

I seem to have wandered rather far afield here. Where was I? Oh, yeah... When I first saw the name Malvina, I thought it was very mellifluous and thus a perfect name for a maker of music. And then I discovered that Malvina Reynolds's best known work was one of the most repulsive songs of the 1960s (which is a very competitive title). One day Mrs Reynolds and her husband were driving from their home in San Francisco to La Honda, where she was booked to sing for the Friends Committee on National Legislation. Motoring through Daly City, California, she was so aghast at the suburban tract housing that had sprung up everywhere that she pulled over, got her hubby to take the wheel, and en route to the Committee meeting wrote:

Little Boxes on the hillside

Little Boxes made of ticky-tacky

Little Boxes, Little Boxes,

Little Boxes all the same...

And then she moved on to the people inside the little boxes:

And they all play on the golf-course

And drink their martini dry

And they all have pretty children...

And they all get put in boxes

And they all come out the same...

Notwithstanding its condescension, it became a hit - accessorized below with equally condescending images:

The lyric is one giant sneer at so-called suburban conformity. Tom Lehrer, a far more gifted social observer, called it "the most sanctimonious song ever written". If you go to those post-war sub-divisions now, the little boxes are individualized with dormers and porches and bay windows and a spare room above the garage and climbing ivy up to the roof. If Malvina Reynolds wanted to see little people living little lives in little boxes, she should have seen the totalitarian housing the Communists warehoused their citizens in throughout the Warsaw Pact: two-room flats, seriously little boxes, and all identical.

But the tune was child-like, and the composer's pal Pete Seeger succeeded in passing it off as a kind of kiddie song, and for a while the word "ticky-tacky" entered the vernacular - with the result that this preening, snobbish horror remains Malvina Reynolds' best known song in the United States.

She was born Malvina Milder in San Francisco in 1900, the daughter of socialist immigrant non-observant Jews. There are all kinds of little boxes: unlike many red-diaper babies, she came out the same, and stayed the same. By the age of ten she was contributing poems to The International Socialist Review:

Workers of the World unite!

And make your heavy burden light;

Let Tyranny fade away,

Let us see the better day.

The day when everyone must work

They'll get nothing, those who shirk,

Those who do all will get the all,

Those who do little will get the small

And everything will be alright,

If the workers of the world unite.From our little Comrade

Malvina Milder

That's certainly a precocious effort for a ten-year old, albeit not quite on message for Bernie and AOC: These days socialists no longer demand that "everyone must work" and that "those who shirk" should "get nothing". Au contraire.

"Our little Comrade" went to Berkeley, married a labor organizer and never strayed too far from the Bay Area. The Grade Five socialist apparently gave no thought to setting her injunctions against shirkers to music until, well into middle-age, she went to a Pete Seeger gig:

It was in 1947, at a hootenanny in Los Angeles, a middle-aged woman asked if she could speak to me. 'What is it?' says I. 'Well, I need more time than we have here.'

Next day she came to where I and my small family were staying, and said 'I'd like to try doing what you do - sing for unions, for people trying to do something good in their corner of the world.' I said, well you don't get rich but you meet all sorts of wonderful people. I probably told her to get on the phone when she read the papers about something interesting going on, and tell 'em she had a song which would hit the spot for their meeting.

She was forty-six or forty-seven, had a shock of beautiful white hair. I was twenty-eight; I remember thinking 'Gee, she's kinda old to get started.' I had a lot to learn. Pretty soon she was turning out song after song after song!

It wasn't all paeans to the tireless working man. In 1977, a year before her death, Malvina Reynolds told an interviewer that once in a while she had something she wanted to say to children:

I remember how it was when I was little. I know youngsters hate to go to bed at night because it seems like, as far as they're concerned, it is the end of the world. Going to sleep means you are going to be cut off from everything, and I wanted to help them understand that they were heading somewhere, when they got into bed, that they were heading for morning.

And so, in 1957, she wrote:

Train whistle blowing

Makes a sleepy noise

Underneath their blankets

Go all the girls and boysHeading from the station

Out along the bay

All bound for Morningtown

Many miles away...

It's just a terrific song idea - although she wasn't the first to get to it. The notion of sleep as a child's journey through night till morning had been given the once-over by many Tin Pan Alleymen - we played one such early train song on a recent Hundred Years Ago Show. Here by way of contrast the nocturnal ride is via dreamboat:

That's all very well, but it has to be said that Mrs Reynolds did it better. There is something beguiling about the concept of "Morningtown", and in the author's plans for the expedition the children are running the show:

Sarah's at the engine

Tony rings the bell

John swings the lantern

To show that all is well...

If you've seen the mockumentary A Mighty Wind, you'll be familiar with the faux-folk group the "Folksmen". They conjure at least in part the Limelighters, a now obscure combo who nevertheless in 1962 made the first recording of "Morningtown Ride":

The Limeliters made a two-thirds cast change to the lyric's dramatis personae:

Judy's at the engine

Tony rings the bell

Seymour swings the lantern

To show that all is well...

Seymour? Where'd that come from? The Performer's Guide to Lyric Changes by Seymour Sales? Two years later, for the Seekers' first outing to Morningtown, the verse had been (wisely, in my opinion) universalized:

Driver at the engine

Fireman rings the bell

Sandman swings the lantern

To show that all is well...

"Sandman" is a kind of pun. He's the traditional bringer of sleep and dreams (as in "Mr Sandman"), but, if you know your locomotives, you'll be aware that trains come equipped with a sandbox, to spray sand on the tracks in rainy weather to assist traction. On this ride, I'd rather have a sandman than John or Seymour. It's comforting:

Maybe it is raining

Where our train will ride

All the little travelers

Are warm and snug insideRockin', rollin', ridin'

Out along the bay

All bound for Morningtown

Many miles away...

When I played the Seekers on our Australia Day special a few years back, many antipodean listeners insisted that the song is about Mornington, a Victorian seaside town about a two-hour train ride south from Melbourne. For example, John Walters:

I always understood that the journey from Melbourne to Mornington is (at least partially) what the song is about.

That's a coincidence. It's no more about Mornington, Oz than it is about Mornington Crescent (of BBC "I'm Sorry I Haven't A Clue" fame). It's an American song by a California writer who never set foot in Australia. "Morningtown" is an idea: the land of the new day after a long journey through the night.

Shortly after the Seekers' hit single, there was a spirited recording made by Stan Butcher, His Birds and Brass. The LP cover featured a representative of both the brass and the birds, although it's the bird that registers. Anyway Stan's particular combination of musicians and vocalists advertises its modus operandi in its very name: First the trumpets and trombones take a crack at a melodic phrase, and then the dolly birds ooh and ah their way through it. Thus on "Morningtown Ride" the brass cheep out the first phrase very perkily, and Stan's birds respond with "Dup-dup-dur-dur-dup":

You only have to play the opening bars and two generations of British children will instantly recognize it as the theme to the BBC's "Junior Choice" with Ed Stewart. Stewpot died half-a-decade back, after playing "Morningtown Ride" one last time on the special Christmas edition of "Junior Choice". Here he is a few years earlier, warbling along on the fortieth anniversary show:

Speaking of Christmas specials, the Seekers, anticipating Love Actually, eventually remade "Morningtown Ride" as the title track of their Yuletide album - a rather awkward mash-up of nocturnal narratives that in the end makes Morningtown less special.

Hmm. How did the creator of the song think it should be sung? Well, Malvina Reynolds recorded "Morningtown" herself in 1970, but she was not a distinguished performer even of her own work:

Brahms' Lullaby is more interesting musically but Mrs Reynolds has the edge lyrically: This lullaby doesn't simply instruct you to go to sleep, but presents it as a great night-long adventure. The tune is good enough, a bit of a round-trip train journey in itself, climbing up the hill to "...sleepy noise" in the first four bars and then back down to "girls and boys" at the station in the second four. But it's Judith Durham's golden voice and Athol, Bruce and Keith's harmonies that seem to conjure within that one word "Morningtown" a whole world of anticipated magic. Had the song been written by, say, Irving Berlin, Morningtown would have been just around the corner rather than "many miles away". And somehow the track lengthens across the horizon as the song goes on:

Somewhere there is sunshine

Somewhere there is day

Somewhere there is Morningtown...

Professor Charles Smith of Western Kentucky University observed:

It is difficult to dismiss this work as 'just another children's song': it has a bit too much backbone. Notice in particular how Malvina concludes the song with the rather sobering lines: 'Somewhere there is sunshine, somewhere there is day, somewhere there is Morningtown, many miles away.' Surely the deliberate use of the word 'somewhere' here - three times, where it is absent in the earlier verses - does not help allay fears there might be storms to weather before the nirvanic destination (i.e., 'Morningtown') is finally achieved..? From the perspective of her many years Malvina knew as well as anyone that 'sunshine' and 'day' are not givens in the voyage of life, they are earned. And yet the song seems hopeful. In the end it may indeed send a message that is - to a child anyway - warm and comforting, but we who sing this song to our children no longer find ourselves in this blissful place...

As Johnny Mercer, who knew a thing or two about this territory, wrote a few years after "Morningtown Ride":

The Days of Wine and Roses

Laugh and run away

Like a child at play

Through a meadow land

Toward a closing door

A door marked 'Nevermore'...

It's so easy to ride to Morningtown when you're seven years old, and it gets harder and harder as the decades roll by. In Australia almost exactly five years ago, I mentioned in response to the Foreign Minister Julie Bishop's too kind words about me that these days I trudge up to greet the sandman increasingly burdened by the gloom of our times. At a certain point, we'd all love to be spirited along the bay to emerge from our slumbers in Morningtown. But the past, and childhood particularly, is another country:

Somewhere there is sunshine

Somewhere there is day

Somewhere there is Morningtown

Many miles awayRockin', rollin', ridin'

Out along the bay

All bound for Morningtown

Many miles awayAll bound for Morningtown

Many miles away.

Are we too late? Is that the lonesome whistle down the track? As Shakespeare almost said: To sleep, perchance to steam...

~If you're a Steyn Clubber and you feel that, with this column, his choo-choo jumped the tracks, do let loose in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges, so get to it! For more on the Club, see here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.