This week's Song of the Week was the Number One song in America exactly ninety years ago, and was still generating bestselling records over half-a-century later. A lot of people recorded it nine decades back - Bing Crosby, Leo Reisman, Ben Bernie - and ever more in the years since. But this was where it began - February 1931, and a blockbuster hit for Ted Lewis and his band:

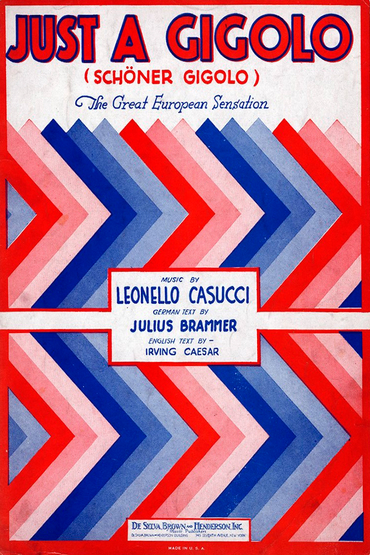

If you're used to its late-twentieth-century iterations, dear old Ted's tempo will strike you as a touch lugubrious. But that's how it sounded, almost always, for its first quarter-century - at least in English. "Just A Gigolo" was born thousands of miles to the east of Tin Pan Alley as a melancholic Teutonic reflection on what had happened to the Habsburg Empire in the wake of the Great War. In 1928, a composer called Leonello Casucci and a lyricist by the name of Julius Brammer enjoyed a big hit in Austria called "Schöner Gigolo":

I know nothing about the composer, Signor Casucci, but a little more about the lyricist, Herr Brammer, because he wrote the libretti for Countess Maritza and some of the other big-time Silver Age Viennese operettas. "Schöner Gigolo" was his biggest ever pop hit, and, as was often the case back then, an American publisher noticed its success in Europe and snapped up the English-language rights. (One feature of our supposedly more "multicultural" age is how comparatively parochial the music biz is compared to eighty years ago: when was the last time you heard an Austrian tune on the Billboard Hot One Hundred?)

The US publisher handed it to my old friend Irving Caesar to adapt. As you'll know if you read my obituary of him in Mark Steyn's Passing Parade, I adored Caesar, mainly because, to the impressionable lad I was back then, he was exactly what you were looking for in an old-time songwriter: A small man with a shock of white hair and a bow tie, he chewed cigars, sang songs, and regaled you with well-honed anecdotage about his biggest hits - and flops.

Among the latter was a disaster of a Broadway show called My Dear Public, which earned him the worst notices he'd ever had. Irving did quadruple-duty as the show's lyricist, librettist, co-composer and producer. "Okay, they didn't like it," he told Oscar Hammerstein. "But why blame me?"

One day he went to a costume party dressed as his near namesake, Julius Caesar, in toga and laurel leaves. En route he was pulled over for speeding. "Name?" demanded the cop.

"Caesar," said Caesar.

"A wiseguy, huh?"

When I knew him, he lived in the Omni Park Central in New York, having moved in many decades and several remodelings and corporate ownerships earlier. So you'd pass through a lobby of chrome or leather or whatever that season's hotel decor was, and then cross Caesar's threshold and step back through the years, to a Tin Pan Alley publishing house, circa 1924. Irving would recline in his BarcaLounger, singing "Swanee" or "Tea For Two" or another of his many hits, squeaking the chair in time to the music. I asked him about "Just A Gigolo" and, for a few minutes, he stopped squeaking.

His credo was simple: "I write fast. Sometimes lousy, but always fast." So, when he was handed "Schöner Gigolo", he decided he liked the tune - a simple melody, but given a wistful bittersweet quality by the underlying harmony - and that he'd get someone to translate the German text and tell him what it was all about, and then he'd write it, fast. When he saw the translation, he realized Julius Brammer had written an allegory of Austro-Hungarian post-imperial decline in which a former hussar who still recalls the good old days is forced to eke out a living as a gigolo. Caesar reckoned that nobody in America cared about social upheaval in the Habsburg Empire but thought the basic scenario had potential. "I moved him to France," he told me, "and then I begin by describing him":

'Twas in a Paris cafe that first I found him

He was a Frenchman, a hero of the war

But war was over, and here's how peace had crowned him

A few cheap medals to wear, and nothing more

Now ev'ry night in this same cafe you'll find him

And as he strolls by, the ladies hear him say,

'If you admire me

Please hire me...'

I loved how Irving sang that line to me in his BarcaLounger that day: "If you admire me/Please hire me..." He put a real yearning into it, really getting into the part. Which was impressive, because it would be hard to conjure anything less like a Parisian gigolo than a genial bachelor pushing ninety. (Irving told me he didn't want to get married too young. In the end, he waited till he was a hundred to tie the knot, and died the following year at 101.) Anyway, after that bit of Jolsonesque pleading, complete with outstretched arms, he went into the chorus. "Schöner Gigolo" translates as "beautiful gigolo", but Caesar decided to go for something more alliterative:

I'm Just A Gigolo

Ev'rywhere I go

People know the part I'm playing...

That alliteration is really a tremendous improvement on "Schöner Gigolo", which may be why "Just a Gigolo" found itself transferred to the silver screen as the title for a 1931 feature film and a 1932 Betty Boop cartoon - and eventually a 1978 David Bowie pic:

That's not the late Mr Bowie warbling the song but Marlene Dietrich, in what would prove her final motion picture. The film bombed, and Bowie took to calling it "my thirty-two Elvis movies rolled into one". But did you notice something?

I'm Just A Gigolo

Ev'rywhere I go

People know the part I'm playing

Paid for ev'ry dance

Selling each romance

Ev'ry night some heart betraying...

And, if you know the song from either of the two most famous records of it, that line is most likely unfamiliar to you. A quarter-century after its birth in Vienna, way over in Las Vegas Louis Prima and his great saxophonist Sam Butera decided to reconstruct the number. So here's how Louis sang it:

I'm Just A Gigolo

Ev'rywhere I go

People know the part I'm playing

Paid for ev'ry dance

Selling each romance

Oooooooh, what they're saying...

Treat yourself in this miserable locked-down world to three-and-a-quarter minutes of sheer joy from Prima, Butera and Louis' stony-faced missus Keely Smith:

Did you see what he did there?

When the end comes, I know

They'll say Just A Gigolo

Life goes on without me

'Coz

I...

Ain't Got Nobody...

Somehow, Prima and Butera had hooked up Julius Brammer's metaphor for post-Habsburg Austria with a somewhat self-pitying ballad from 1915, written by their fellow son of New Orleans, Spencer Williams. The composer of "Basin Street Blues", "I've Found A New Baby", "Everybody Loves My Baby" and more, Williams has an enviable catalogue. But in 1956, having relocated to Stockholm, he'd more or less given up on "I Ain't Got Nobody", for whom there'd been few takers since the bluesier mamas like Sophie Tucker and Bessie Smith had given it some mileage back in the Twenties. Who knows how or why the muse descends? But Butera and Prima had wound up combining "Just A Gigolo" with "I Ain't Got Nobody", and made it a nightly Vegas ritual:

I'm so sad and lonely

(Sadandlonelysadandlonely)

Won't some sweet mama

Come and take a chance with me?

('Cause I ain't so bad...)

That lyric's wandering some ways from the 1915 original, too. But the Prima medley rescued the song, using the exotic scenario of "Just A Gigolo" as a foundation to pile on, tongue in cheek, the self-pity of "Nobody".

Prima's act was billed as "The Wildest Show In Vegas". And they were: Louis, Keely, Sam Butera and the Witnesses, together in a rowdy, bawdy on-stage party that did a lot to define the desert resort in its early days. "It's entertainment, man," Sam would tell anyone who wanted to know the secret: You could be the most gifted musician on the planet, but, if you didn't know how to "get happy with the people", it was deadsville, baby. And Butera, like his mentor Prima, certainly knew how to get happy with the people. The on-stage dueling - with Louis scatting lines of ever more frenetic gibberish and demanding that Sam instantly recapitulate them on the sax - delighted audiences right up until the day, in 1975, when Prima fell into an irreversible coma. After the shock, Butera picked up his horn and went back to work, providing customers for another quarter-century almost as much fun sans Prima.

Almost.

Underneath the kibbitzing was a gifted musician, and one of the best hard-swinging tenor saxes around. Singers loved him, which may be why he gets more namechecks on studio recordings than almost any other soloist, as Sammy Davis Jr or whoever wraps up the vocal chorus and hands on to Butera with "Blow, Sam!" or similar exhortation. My favorite is Frank Sinatra, doing some piece of Neil Diamond fluff at a recording session during his mid-Seventies artistic low point. It was a little nuthin' song called "Stargazer" tricked out with such unSinatra instrumentation as a tuba and a banjo (the first on a Frank track since "Tennessee Newsboy" a quarter-century earlier). But, for whatever reason, they'd also booked Sam Butera. And, in the second chorus, the singer more or less gives up on the vapid lyric in mid-word - "Hey, Starga..." - and barks at Butera, "Jump on it, Sam. Get all over that thing." And Sam does, in one great joyous honking blast that's way better than the song deserves.

Butera started out accompanying the strippers in a club on Bourbon Street in New Orleans. Playing saxophone while Lili Christine the Cat Girl disrobed brought in 700 bucks a week, which wasn't bad in those days. Then Louis Prima came in looking for a sax player for his new gig at the Sahara in Vegas. He offered Butera a third of what he was getting for backing strippers, and Mrs Butera didn't care for the desert, but Sam had a feeling things were going to work out. And they did - once he started writing arrangements for the band. "That's when it happened," he said. "The sound, you know?" The sound we still know: The shuffle, the blues jumps, the jivin' an' wailin', the unreverential raucousness that made Prima a Vegas sensation and gave his musical career a second act way bigger than the first. The charts on most of the big songs were Butera's: "Jump, Jive An' Wail", "That Old Black Magic", "Dig That Crazy Chick", "I Wanna Be Like You" (from The Jungle Book). Prima had been around a couple of decades and liked to do his old songs, like "Angelina" and other Italiano effervescences. So he and Butera got the idea of slamming them all together in medleys. Sometimes the pairings made sense, sometimes not so: There's no particular reason why "When You're Smiling" should be yoked to "The Sheik Of Araby", except that Butera's arrangement makes it irresistible.

But the signature medley, and a highlight of the act for the rest of Prima's career, was that goofy coupling of two half-forgotten songs: "Just A Gigolo" and "I Ain't Got Nobody".

In April 1956, Sinatra's producer Voyle Gilmore brought Prima, Butera and the Witnesses (with Keely Smith among the backing vocalists) into the Capitol studios in Los Angeles and put "Just A Gigolo/I Ain't Got Nobody" down on record. It wasn't a big chart hit, but it became a classic of sorts:

Three decades later, I called Irving Caesar to wish him a happy ninetieth birthday. For an old guy, he always seemed to have a new lease of life, professionally speaking. And so it was this time. "I'm back in the Hit Parade," he barked down the phone. "'Just A Gigolo.' Some black fellow out on the coast covered it."

Actually, it was a white fellow - David Lee Roth of Van Halen - and, if memory serves, he's from Indiana. But, other than that, Caesar had got the essentials right: "Just A Gigolo" was back in the charts. Or, rather, "Just A Gigolo/I Ain't Got Nobody". And, to my amazement, upon hearing the record, I discovered Roth had lifted the Louis Prima medley complete, down to crappy karaoke copies of Prima's idiosyncratic vocal embellishments and a decidedly non-Butera plonking sax:

As I say, I was amazed. Sam Butera, on the other hand, was mad as hell. "He copied my arrangement note for note," Butera told The New York Times, "and I didn't get a dime for it."

As sometimes happens with a particularly strong arrangement, the Louis Prima record had become the song - or, in this case, two songs: Prima and Butera had so overpowered all previous renditions of "Just A Gigolo" and "I Ain't Got Nobody" that, to many members of the public, the two songs had become the front and back halves of a single number. One can forgive such confusion among the citizenry at large, but a professional singer ought not to be under any such misapprehension. Over the years, I've had any number of conversations with vocalists who've said they'd like to do this or that song but can't think of anything to add to the Ella Fitzgerald arrangement or the Peggy Lee chart. I can understand how a singer might do "The Way You Look Tonight" or some other well-worn standard and it might come out only marginally different from some of the other versions. But I really can't understand how any self-respecting performer could lift another act's medley.

Legally, it's a grey area: An arrangement is generally a derivative of a pre-existing work. But an arrangement of a medley as unique as Butera and Prima's comes closer to being a "work" in its own right. Yet we're not talking law here, but of a more basic understanding of creativity and integrity. In essence, David Lee Roth decided to launch his solo career with an act of appropriation. And not only did he lift another guy's arrangement but he couldn't understand why Butera would be miffed about it.

One night, while the Witnesses were playing in Vegas, Roth swung by to catch the act and, afterwards, hailed Butera with a cheery, "Hey, Sam!"

"Who are you?" asked the sax man.

"I'm David Lee Roth," replied the rocker.

"Then where's my money?" said Butera.

Poor old Roth: You can sympathize with his confusion. A couple of years before he decided to pilfer the Prima medley, the Scots rocker Alex Harvey had done the same, and so had the Village People - although in fairness to the latter they at least had sufficient wit and creativity to put it to a disco beat:

There is, in fact, no precedent for a medley so successful that, henceforth, it becomes the only version in which either of its constituent songs are performed. In a way, Sam Butera did his job too well. But, in another sense, it's an especially pointed example of what, in the years after Roth, became an entire genre of rockers singing standards. I don't begrudge the average middle-aged rocker mitigating the usual popster mid-life crisis with the apparently obligatory therapy of a Great American Songbook CD. But I don't think it counts if you just mouth along with some other fellow's record. What do you bring to the table? Cooler hair? Funky shoes? Tighter pants and bigger codpiece? The definition of a standard song is something that can be done in a thousand different ways: slow and dreamy, up and swingin', waltz-time, bossa nova, 35-piece orchestra, solo guitar, Latin, country... Louis Prima took two old songs and made them his own. David Lee Roth took two Louis Prima songs and made you realize how great Prima is, and what a tosspot Roth is.

One day someone will figure out something different to do with "Just A Gigolo", and somewhere on the other side of the planet someone else will come up with a new wrinkle on "I Ain't Got Nobody". But for now those whom Sam Butera joined together no man can put asunder.

Unless you go back to where we came in - a "Schöner Gigolo" in the post-Habsburg twilight:

When the end comes, I know

They'll say Just A Gigolo

Life goes on without me.

~There's more with Mark and Irving Caesar in his classic book Broadway Babies Say Goodnight, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the Steyn store.

If you're a Mark Steyn Club member and you feel Mark is just a musicological gigolo, do let loose in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges, so get to it! For more on the Club, see here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.