Valentine's Day is here: We have a brand new Sunday Poem for you, and some live love songs on the weekend edition of The Mark Steyn Show. But we would be remiss not to include the one explicit Valentine standard. This essay includes material from Mark's book A Song For The Season:

My Funny Valentine

Sweet comic valentine

You make me smile with my heart...

There are thousands of love songs for Valentine's Day but only one great Valentine love song. After Sinatra reintroduced it to the world on the very first track of his very first album for Capitol Records - Songs for Young Lovers in 1954 - everyone and his aunt started singing it, to the point where, at the dawn of the LP era, the joke was that it would be easier to list the albums that didn't feature "My Funny Valentine". Jazz discographers list over 100 performances of the song by Chet Baker alone, starting with his first instrumental recording with Gerry Mulligan in 1952 and then, in '54, the vocal performance that let the world know Mr Baker was not only a trumpeter:

If you're disinclined to riffle through all 100 versions, look for an Italian album called Seven Faces Of Valentine, which features a septet of Chet "Funnies" recorded in Italy between 1975 and 1985. Baker is an extreme case of "Funny Valentine" addiction but by no means alone. In the Fifties, the owner of a club in New York is said to have had a standard contract for vocalists with a clause forbidding them from singing the song. No chance of that today:

Elvis Costello recorded it back in the Seventies, long before the fad for rockers doing standards got going, and in recent years Anita Baker and Rod Stewart, Sting and Sheryl Crow and Christina Aguilera have all had their say on the song. Much of that is directly traceable to the rebirth of the song on Side One Track One of Sinatra's Songs For Young Lovers.

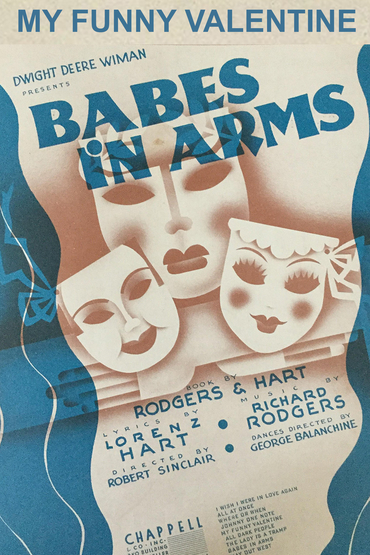

But where did it come from? How did it get that good? It was written by Rodgers & Hart in 1937, for a show called Babes in Arms, and it was sung to the leading man, who was called "Val" - short for "Valentine", an imperfect object of the young lady's affection:

Is your figure less than Greek?

Is your mouth a little weak?

So it was written to be sung to a guy called Valentine. Anything else?

Not really. That's pretty much all we know. As a longtime lover of a-song-is-born anecdotes, I know what I'm looking for in a good and-then-I-wrote story: To take another Rodgers & Hart number, the boys were in a taxi cab with a couple of showgirls and it braked suddenly and threw them forward, and one of the girls said, "Oh, my heart stood still!" And the ol' lightbulb lit up in the songwriters' head, and hey presto, there you are. You want every great song to have that kind of story behind it - especially when it's as iconic an entry in the catalogue as "My Funny Valentine". But sometimes great songs aren't written that way. Sometimes it's just a professional writing assignment - or something closer to Lennon & McCartney's explanation of their work methods:

There are two things we always do when we sit down and write a song. First we sit down. Then we write a song.

I've spent years trying to figure out the spark that lit "My Funny Valentine". I've spoken to cast members of Babes In Arms, and Richard Rodgers' daughter and other friends and family, and come up dry every time. The composer's memoir Musical Stages has nothing to say, in keeping with its generally soporific tone (at one point, Rodgers borrows wholesale a slab of prose from David Ewen's biography of him - a rare example of an autobiographer regarding a biographer as a more reliable guide to himself than he is). The only reference the author makes to one of his best known and most performed and recorded melodies is as follows:

'My Funny Valentine', however, was very much about a specific character in the book; in fact, before the show opened we even changed the character's name to Val.

So you turn to Will Friedwald's 2002 offering, Stardust Memories: A Biography Of Twelve Of America's Most Popular Songs, one of the dozen being "My Funny Valentine". And, amidst all the fine insights into the merits of Miles Davis' '58 reading with John Coltrane versus his '64 performance with Herbie Hancock, it's easy to overlook Mr Friedwald's account of the actual creation of the music and lyric:

At some point during the writing of the Broadway version, Rodgers and Hart came up with the song 'My Funny Valentine'.

And that's it. That's all there is. First they sat down. Then they wrote a song. And we'll never know the process by which Lorenz Hart decided he could use a six-syllable word in a romantic ballad and make it sound utterly natural:

Your looks are laughable

Unphotographable ...

In his book Finishing The Hat, Stephen Sondheim can't resist a big catty sneer:

'Your looks are unphotographable.' Unless the object of the singer's affection is a vampire, surely what Hart means is 'unphotogenic'. Only vampires are unphotographable.

Talk about missing the point.

But, if we don't know a lot about how the song was born, we do know something about the show. One day in 1936, Rodgers & Hart were strolling through Central Park when they were struck by the children playing games, devising the ground rules, inventing their own world. And they started musing on what kids might do if they suddenly needed to come up with some money, and it occurred to them that one thing they might attempt is to put on their own show. This is it, folks: that whole Judy Garland/Mickey Rooney let's-do-the-show-right-here-in-the-barn shtick was born on a walk through Central Park in 1936. Larry Hart liked the idea of doing a musical full of fresh talent, and Dick Rodgers, already well advanced on his evolution into businessman-composer, thought there might be some commercial advantage in mounting a production not dependent on any star names.

So they signed a company of young unknowns, including Alfred Drake and Dan Dailey, and the tap-dancing Nicholas Brothers. The oldest member of the cast was Ray Heatherton, at 25, and the youngest was Harold Nicholas, then twelve. It fell to Mitzi Green, at the tender age of 16, to introduce the world to "My Funny Valentine" on Wednesday April 14th 1937, the opening night of Babes In Arms at the Shubert Theatre on Broadway. In the midst of a plot about youngsters putting on a show in order to avoid being sent to a work farm, and attendant sub-plots about French aviators on transatlantic flights, and a dream ballet about the kids going to Hollywood and meeting their favorite stars, in the midst of all that, Miss Green sang to Ray Middleton:

Behold the way our fine-feathered friend

His virtue doth parade

Thou knowest not, my dim-witted friend

The picture thou hast made

Thy vacant brow and thy tousled hair

Conceal thy good intent

Thou noble, upright, truthful, sincere

And slightly dopey gent

You're...My Funny Valentine...

That's the verse, and it's lovely. Alec Wilder, noting that the published sheet music is printed without any piano accompaniment, called it "an air for a shepherd's pipe", its pastoral purity enhanced by all the archaisms - the "thous" and "thys" and "doths" and "hasts" - which Larry Hart neatly brings down to earth in that "slightly dopey" final line.

In the context of the show, it's wonderful. But I never quite understood why almost every female vocalist from Ella Fitzgerald to Linda Ronstadt to Cristina Aguilera feels obliged to sing it on pop albums far removed from the plot of Babes In Arms. And then I realized, of course, that it's their way of reminding us that, notwithstanding the phenomenal popularity of the Sinatra recording, it's not a guy's song. Male vocalists, from Tony Bennett and Johnny Mathis to Elvis Costello and Michael Bublé, can glide over the chorus and lines like "Is your figure less than Greek?", but the verse makes plain that the number is in the long tradition of songs in which women profess love for imperfect men - see, for example, Kern & Wodehouse's "Bill". So, in insisting on the verse, Fitzgerald, Ronstadt & Co are telling Frank and the boys: this is one part of "Funny Valentine" you guys can never have:

Did the first-night crowd at the Shubert know that they were getting the first rendition of what would become one of the towering standard songs? You couldn't blame them if they'd missed it. Rodgers & Hart's score for Babes In Arms was an embarrassment of riches: "Where Or When", "I Wish I Were In Love Again", "The Lady Is A Tramp", to name only the songs from the show Sinatra eventually recorded. They were all brand new, none ever heard before. You can't fault the audience if some of the take-home tunes got lost in the sheer avalanche.

Yet you can understand why "My Funny Valentine" might not have landed with quite the oomph of the others. For one thing, it doesn't sound like a song for a sixteen-year old. It's rueful and bittersweet and a lot of other adjectives we don't associate with first love. Rodgers usually wrote the tune first and then Hart set the words to it (in Rodgers' later partnership with Oscar Hammerstein, it was the other way around). But it seems possible there was a bit more give-and-take on this occasion: The tune is so responsive to the words, written in the minor key to match the wistfulness of the lyric but then ending up in the major just as the text becomes bold and declarative. The music tells us that, notwithstanding the playful mockery of the words, this love is for real. We'll never know how Richard Rodgers hit upon climbing an octave higher for the dramatic climax of the lyric yet avoided the usual big-note bombast and instead captured all the ache and yearning of the words:

Stay, little valentine, stay!

A love song is a very fragile thing, and the false tinkle of the wrong word on the wrong note can tip the thing into absurdity. Perhaps that fine line is something you can only understand instinctively. Larry Hart certainly did. I mentioned earlier the skilful deployment of that six-syllable word:

Your looks are laughable

Unphotographable ...

But that's more than just songwriting professionalism. It's also autobiographical. To promote the show, the writers gave the usual round of interviews, and a lady from Popular Songs magazine inquired after Hart's own love life. "Love life?" he replied. "I haven't any."

So he was a confirmed bachelor?

"Of course," said Hart. "Nobody would want me."

In 1937, Rodgers & Hart were at the top of their game. Hart was one of the most successful men on Broadway, so how come nobody would want him? Yet nobody did - or so Larry was convinced. He was a misproportioned four-foot-ten, and sensitive to the fact that Rodgers was the normal guy - the one with a wife and kids and the family life he'd never know. The evidence for Hart's sexuality is inconclusive, and any man of 4' 10" winds up making do, regardless of inclination. "Because of his size, the opposite sex was denied him," said Alan Jay Lerner, "so he was forced to find relief in the only other sex left."

Even then, he doesn't seem to have found that much relief. He lived with his mother and various passing aunts, and it was left to his friend, the infamous Doc Bender, to procure for Hart what brief companionship he enjoyed. According to one alleged lover, he was deeply closeted, literally: after sex, he'd get up and go cower in the wardrobe for the rest of the night. Mabel Mercer famously called him the saddest man she ever knew. You can hear it in the songs:

Falling In Love With Love

Is falling for make believe...

But Hart, who never in his life had a girlfriend or boyfriend, could also skewer precisely the assumptions of intimacy. "One of my favorite songs," Mort Shuman, the writer of "Save The Last Dance For Me" and a ton of Elvis songs, once told me, "is 'It Never Entered My Mind'. When Hart wrote...

You have what I lack myself

Now I even have to scratch my back myself

...I thought, yeah, I've always had this little place on my back that I can't quite reach, and I thought about the times I've asked a lover to scratch it for me. That's brilliant writing."

Brilliant, but conjured strictly from Hart's imagination: no one ever scratched his back. By 1937, he'd written a hundred love songs for everyone else, and "Funny Valentine" was one for himself, the one he'd like to have had someone sing to him:

Is your figure less than Greek?

Is your mouth a little weak?

When you open it to speak

Are you smart?

But don't change a hair for me...

No one ever did sing it to him.

To listen to the score of Babes In Arms is to hear Rodgers and Hart at their very best, yet the show marked the gradual acceleration of the team's diverging paths: Rodgers, disciplined and ambitious, was now the dominant partner and en route to the heights he would achieve as composer-publisher-producer with Oscar Hammerstein; Hart, mercurial and indifferent, was on the beginning of a slippery slide into the abyss. He would have made a funny valentine for all kinds of women - like Vivienne Segal, the actress he adored - but none would have him.

Pre-Sinatra, recordings of the song were left mostly to the ladies and inclined to the melancholic feel of the original. Listen to Mary Martin's recording from the show's revival in 1951. This is how Rodgers heard the song - the only way he heard the song:

If you rushed out to buy Songs for Young Lovers in 1954, you knew something different was going on from the moment the platter hit the turntable: No verse, no real intro other than a couple of chords and a gossamer brush of strings, and then Frank's into the lyric. It's a lovely arrangement, conducted by Nelson Riddle but from a George Siravo chart that had been sitting around in a drawer for a couple of years. Sinatra wasn't always comfortable in waltz time: he was a 4/4 guy and he could sometimes sound a little tentative in 3/4. Yet, when Siravo's arrangement shifts into waltz time halfway through, Sinatra doesn't "shift" so much as waft across the text in three-quarter time. He floats, effortlessly and beautifully:

That's the "Funny Valentine" that became a February 14th tradition.

Across the next four decades, the song fell in and out of Frank's book, and, to most of us, it was a surprise to find it on his second celebrity Duets album in 1994, albeit shoehorned into an awkward medley with Lorrie Morgan warbling "How Do You Keep The Music Playing?"

There's nothing wrong with Miss Morgan's vocal. It's just that neither she nor her song seem to have anything to do with "My Funny Valentine". On the other hand, Patrick Williams' new arrangement of "Valentine" is just ravishing. In November 1953, Frank's original ended with a brief countermelody reminiscent of Gershwin's "Bess, You Is My Woman Now". Forty years later, on October 14th 1993, on one of the last occasions he would ever set foot in a recording studio, Sinatra made what had been hinted at all those years earlier explicit. Pat Williams extends the Porgy And Bess allusion into a gorgeous coda, in which the old lion sings "Morning time... and evening time... and summer time... and winter time..." Sinatra loved the Williams chart and took to singing it, detached from the Morgan medley, in concert in the months after the session: in a six-decade career, it was the very last arrangement added to the Sinatra act.

Richard Rodgers wouldn't have cared for the arrangement, any more than he did for Sinatra's first bite of the cherry. He liked the song just so, and didn't see the point of what the Franks and Chets and Ellas did to it, never mind the Elvis Costellos and Sheryl Crows. As for Larry Hart, he never knew "My Funny Valentine" as a great standard. In 1943, on the first night of a Broadway revival of A Connecticut Yankee, a drunken Hart was ejected from the theatre. As usual, he'd lost his overcoat, but this time he caught a chill, and died in hospital a few days later. His last words were: "What have I lived for?"

Anyone who's fallen in love to a Rodgers & Hart song could answer that for him. That last Sinatra recording spells it out: You're "My Funny Valentine" - "morning time and evening time and summertime and wintertime" - and, as raw and ragged as his voice is, you realize that, across the decades, the promise of the song has come true: This is an eternal love.

Or as the song says:

Each day is Valentine's day.

~"My Funny Valentine" is one of many classic seasonal songs discussed in Mark's book A Song For The Season. Personally autographed copies of both books are exclusively available from the Steyn store - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter your promo code at checkout to benefit from our special member pricing.

Also for Steyn Club members: If you feel Mark's essay is laughable, unmonographable, do let loose in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges, so get to it! For more on the Club, see here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.