Here's the thirteenth episode of our current Tale for Our Time: Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell's tale of life in a 24/7 surveillance state. No chance of that, right?

In tonight's episode Winston Smith goes on a date - which requires a degree of cunning:

He was a bit early. There had been no difficulties about the journey, and the girl was so evidently experienced that he was less frightened than he would normally have been. Presumably she could be trusted to find a safe place. In general you could not assume that you were much safer in the country than in London. There were no telescreens, of course, but there was always the danger of concealed microphones by which your voice might be picked up and recognized; besides, it was not easy to make a journey by yourself without attracting attention. For distances of less than 100 kilometres it was not necessary to get your passport endorsed, but sometimes there were patrols hanging about the railway stations, who examined the papers of any Party member they found there and asked awkward questions. However, no patrols had appeared, and on the walk from the station he had made sure by cautious backward glances that he was not being followed.

"For distances of less than 100 kilometres it was not necessary to get your passport endorsed": Ah, happy times. In the last year, across many parts of the western world, citizens have accepted that the state can confine you to within five kilometres of your home (Ireland and Victoria, for example) and there are indeed "patrols hanging about the railway stations" demanding to know what you're doing and where you're going. And the nightly curfew that descends twenty minutes north of me at the Quebec border is, in fact, more restrictive than Orwell's.

Members of The Mark Steyn Club can hear me read Part Thirteen of Nineteen Eighty-Four simply by clicking here and logging-in. Earlier episodes can be found here.

Over the last week I've been a little coy and evasive about our musical theme for Nineteen Eighty-Four, and it's driving Michelle Dulak bonkers:

Mark, if you don't tell us who wrote the music within twenty-four hours, I shall burst, and you'll be out one First Day Founding Member.

Well, if you insist - and, to give credit where it's due, Michelle came closer than anyone else in identifying the piece we're using. I wanted something a little bit more than a composer who happens to live in a totalitarian state and goes along to get along - because Orwell's novel is itself rather more than that: it is about the total submission of man to the state.

Many years ago I had lunch with Andrew Lloyd Webber at his country pad at Sydmonton. And Andrew wanted to talk about Prokofiev. About whom I knew a little: I get a bit tired of Peter and the Wolf, but I like Love for Three Oranges and I always used to play the troika from Lieutenant Kijé on my Christmas show. But Andrew adores the guy: He regards Prokofiev and Richard Rodgers as the two greatest composers of the twentieth century. As usual, he goes too far: He cited the third movement of the seventh piano sonata as protean rock'n'roll, etc. But enthusiasm is infectious, and so, when I got back to town that evening, I started listening to Prokofiev in more or less chronological order.

And I loved him - until I got to his late work. Which brings us back to Michelle's email of a few days ago:

OK, Mark, now you have me wondering about the music in earnest. So, not Shostakovich. Then I'm inclined to guess some Soviet composer more toadyish than he. Kabalevsky. Late Prokofiev (when he'd returned to the USSR for good, and was writing things like The Story of a Real Man). Khachaturian, maybe. Or -- my best guess -- Tikhon Khrennikov.

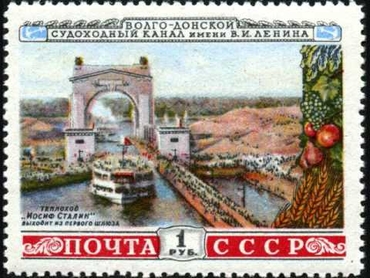

But who really cares if the likes of Khrennikov or Kabalevsky are toadies? A great composer is a far greater bauble for Stalin. After being denounced by the Soviets for "bourgeois formalism", Prokofiev found composition stressful and was advised by his doctor to limit himself to no more than an hour per day. And when I heard The Meeting of the Volga and the Don, from 1951, I heard not the composer of Lieutenant Kijé, but only a man so broken by the state that he has been terrorized into utter banality - which is almost too perfectly Orwellian. So I pressed into service a very third-rate piece of music because it shows how even the greatest artist can be utterly crushed by totalitarian barbarians.

I have a vague memory of bringing it up with Andrew at his sixtieth-birthday bash a few years ago, but somebody interceded, so I never found out what he made of it. Poor old Prokofiev died on the same day as Stalin - March 5th 1953 - so nobody paid any attention. He lived near Red Square, so because of all the mourners ululating over the great monster the hearse couldn't get anywhere near Prokofiev's flat. His coffin had to be taken on foot by friends through back streets against the constant swarm of grieving Stalinists coming in the opposite direction. There is an awesome symbolic power in that.

But congratulations, Michelle: You called it as "late Prokofiev".

Oh, just to cheer us all up, here's that troika:

If you've yet to hear any of our Tales for Our Time, you can do so by joining The Mark Steyn Club. For more details, see here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership. I'll be hosting Part Fourteen of Nineteen Eighty-Four right here tomorrow evening.