Some years ago, the late Mort Shuman, a marvelous composer and one of the first generation of rock'n'roll songwriters, took me to lunch. Mort had written "Why Must I Be A Teenager In Love?" and "Can't Get Used To Losing You" and a bunch of stuff for Elvis, including "Mess O' Blues", "Suspicion" and "Viva Las Vegas". But, like most successful music biz types, he wanted to talk about what he was doing next. So, after the usual pleasantries, he slid across the table a script bearing the title Save The Last Dance For Me - after his Number One hit for the Drifters.

"It's a musical," he said, "about the Cuban missile crisis."

Now I generally subscribe to Tim Rice's rule - that, if somebody says wow, what a great idea for a musical, it almost certainly isn't. But that doesn't mean the inverse applies - that, if something sounds like a terrible idea for a musical, it must be a surefire smash. So, when Mort said, "What do you think?", I was prepared to concede there might possibly be a great musical lurking somewhere in the Cuban missile crisis, but I was less persuaded that there was a great musical about the Cuban missile crisis set to all Mort's old pop hits of the period. "'Save The Last Dance For Me' doesn't address the Cuban missile crisis directly," explained Mort.

"That's true," I said.

"But it comments on it obliquely. I mean, it's literally the last dance. The last dance before the end of the world."

Hmm. "Suspicion" was also in the show, because it commented, equally obliquely, on the mutual suspicion between Kennedy and Krushchev or some such.

Well, Save The Last Dance For Me never happened. But, since then, I've seen at least two other putative scripts for Cuban missile-crisis musicals, both of which made me regret I hadn't been more enthusiastic about Mort's. After the hell of 2020, I miss old-school threats, like mushroom clouds on the far horizon (I doubt American nukes will ever again be dropped on anyone) and have come to admire the sly effectiveness of subtler threats. Either way, I am kinda sorta in a vague "last dance before the end of the world" mood - except, of course, that under Dr Fauci in America and Professor Pantsdown in the UK dancing is forbidden as zealously as it was by the Taliban.

Anyway, for now, the most successful musicalization of that moment in 1962 when the world trembled on the nuclear brink remains this:

Said the little lamb to the shepherd boy,

'Do You Hear What I Hear?

Ringing through the sky shepherd boy

Do You Hear What I Hear?'

Do you hear echoes of the Cuban missile crisis in that? "Do You Hear What I Hear?" was co-written by Gloria Shayne, who wrote other songs which enjoyed some modest success - "Goodbye, Cruel World", "Rain, Rain, Go Away" and, for Andy Williams, "Almost There", one of those consummate MOR charmers that seemed like nothing at the time but which, in an era of bombastic overwrought power ballads, I rather miss. Still, nothing else in the Shayne catalogue will endure as long as her lasting contribution to the Christmas season - and we owe it all to the Cuban missile crisis:

Back in 1952, Gloria Shayne had been the pianist in the dining room of a New York hotel when a young man walked in, took one look at the gal at the keyboard, and went up and introduced himself. He was a Frenchman who spoke very little English, she was an American who spoke even less French. She liked pop music, he had come to America to be a classical musician. Yet within a month they were married. Flash forward ten years: Noël Regney's English has improved, and, although he still hasn't made his name in serious music, he's learned to appreciate American pop music since his wife hit the jackpot with "Goodbye, Cruel World". They even write songs together - usually with Noël writing the music, and Gloria the lyrics.

But not this time. Noël Regney had had a lively war. Born in Strasbourg, he'd been conscripted, after the German invasion, into the army of the Reich. And, although he soon deserted and joined the Resistance, he stayed in German uniform long enough to lead his platoon intentionally into the path of a group of French partisans, who wound up shooting him. After the liberation of his country, he went east to be the musical director of the Indochinese service of Radio France, and found himself in the middle of a new conflict. He thought the Second World War was so terrible that it must surely be the end of all war. But here it was - October 1962 - and as he saw it Washington and Moscow were playing a dangerous game of nuclear brinksmanship over Soviet missiles in Cuba. On the streets of Manhattan, he saw two infants in strollers being wheeled by their mothers along the sidewalk, and decided he wanted to write something for them. Not music, but words: A poem.He remembered scenes from his own childhood - sheep grazing in the pasture of the beautiful campagne - and he had the image he needed:

Said the wind to the little lamb,

'Do you see what I see?

Way up in the sky, little lamb

Do you see what I see?

A star, a star

Dancing in the night

With a tail as big as a kite.'

He wrote a tune to go with it, too, but he decided it wasn't right, and turned to his wife. "When he finished," said Gloria, "Noël gave it to me and asked me to write the music. He said he wanted me to do it because he didn't want the song to be too classical. I read over the lyrics, then went shopping. I was going to Bloomingdale's when I thought of the first music line."

It was only when she got home and played the tune for her husband that she realized she'd made a mistake, and had added one note more to that first line than the lyric required. But Noel loved the melody and didn't want her to change a thing. So he went back to his poem and added a syllable for the spare note:

Said the night wind to the little lamb...

Gloria asked for one other text change: "A tail as big as a kite" didn't sound right to her ears: somehow it wasn't quite American English. But Noël put his foot down on that one: those words were staying, just as they were. "He was right," she later told Yuletide musical archivist Ace Collins. "It is a line that people dearly love." It's perhaps the most vivid and memorable in the song, and a good example of how a phrase you might have no use for as a piece of speech can be transformed by music. The star dancing in the night with a tail as big as a kite is a rare moment of poetic imagery in a lyric that's otherwise baldly descriptive. It's slightly off-kilter - a tail as long as a kite, surely? - but "big" makes it more childlike and wondering.

The simple structure of the song is very effective - four verses, passing the story from the night wind to the little lamb, the little lamb to the shepherd boy, the shepherd boy to the mighty king, and finally the mighty king to the people. The repetition of "a star, a star/Dancing in the night" is matched by "a song, a song/High above the trees", and "a child, a child/Shivers in the cold..." And at the end Noël Regney finally spelled out what was on his mind in that fall of 1962:

Said the king to the people everywhere,

'Listen to what I say!

Pray for peace, people everywhere

Listen to what I say!

The child, the child

Sleeping in the night,

He will bring us goodness and light.

M and Mme Regney took their song to the Regency publishing company, and Regency immediately got hold of Harry Simeone. You can understand why. The Harry Simeone Chorale had had a huge hit four years earlier with "The Little Drummer Boy", and to a casual listener "Do You Hear What I Hear?" can easily sound like "The Little Drummer Boy" sideways. Both tunes share a kind of simplistic formality, and the words of the later song echo the first: "Do You Hear?" reprises "Drummer Boy"'s king and baby (actually, in the first song, the king is the baby) and one half of "the ox and lamb", and the little shepherd boy is clearly a kindred spirit of the little drummer boy. So the Simeone Chorale recorded it, put it out for Thanksgiving 1962, and sold a quarter-million copies in its first week:

There were stories in the papers about drivers hearing it on the radio and pulling over on to the shoulder to listen to the lyrics. Regney and Shayne had written a song so powerful they couldn't even get through it themselves without dissolving into tears. "We couldn't sing it," said Gloria. "Our little song broke us up. You must realize there was a threat of nuclear war at the time."

But threats of nuclear war come and go; a good song is forever. What turned "Do You Hear What I Hear?" from a peace anthem to a seasonal standard was a recording the following year by Mister White Christmas himself, Bing Crosby. Bing's warm dramatic baritone drew out the words in ways that the 25 voices of the Harry Simeone Chorale simply couldn't. When I see these lyrics on paper, my mind's ear hears them in Crosby's voice:

Said the shepherd boy to the mighty king,

'Do you know what I know?

In your palace warm, mighty king

Do you know what I know?

A child, a child

Shivers in the cold

Let us bring him silver and gold

Let us bring him silver and gold...'

Bing's version sold a million copies, and the song never looked back. Noël Regney went on to write the signature song of the Singing Nun, "Dominique", an international smash in whose success the Kennedy Administration again played a part. Following the assassination of the President in 1963, Top 40 radio stations anxious to return to their regular preformat opted to play softer songs rather than the hard rockers, and "Dominique", a bland bit of bouncy Europop, happened to be one of the softest things on hand, and all the better for having a non-English lyric. It helped make "Dominique" the first Belgian single to get to Number One in America:

The Singing Nun's career dissolved in odes to contraception, tax problems, lesbianism and eventually suicide: She and her partner of ten years concluded that they could not pay the Belgian revenue authorities what they were demanding, and both women killed themselves - on the very day that, unbeknown to them, the Belgian songwriters' agency sent her a royalty check that would have more than covered what she owed the government. It is difficult to imagine circumstances in which "Dominique" would ever again become a popular song.

But "Do You Hear What I Hear?" gets bigger every year. It's especially popular with emoting ladies - Gladys Knight, Céline Dion, Vanessa Williams, Martina McBride, and many other melisma queens. Indeed, in recent years it seems to have become something of a woman's song, which I regret if only because I think it sounds better in a slightly formal male baritone than in a pseudo-soulful ululatory pile-up that reduces the crisp, spare Regney lyric to rubble. As for the authors' own favorite version, they were never in any doubt about that: "When Robert Goulet came to the line 'Pray for peace, people everywhere', he almost shouted those words out," said Gloria Shayne. "It was so powerful." A little too much aimless backphrasing for my taste, but chacun à son goût:

"I am amazed that people can think they know the song," said Noël Regney, "and not know it is a prayer for peace." Ah, but most great popular art wiggles free of its creator. And so many if not most of those singing along to "Do You Hear What I Hear?" will have no idea that it has anything to do with some ancient flash point of the Cold War. Which is as it should be. Noël Regney and Gloria Shayne eventually divorced. The man who wrote those powerful words was hit by a stroke and ended his days unable to speak. The woman who wrote that melody was struck by cancer and unable to play the piano. But their song lives on, with a tail stretching across the decades:

Said the night wind to the little lamb,

'Do you see what I see?

Way up in the sky, little lamb

Do you see what I see?

A star, a star

Dancing in the night

With a tail as big as a kite.'

Noël Regney: the first Noël to write an American Christmas classic, even if it took the Cuban missile crisis to inspire him.

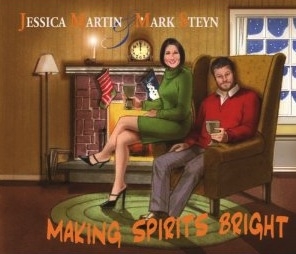

~There's an hour's worth of great seasonal music on Making Spirits Bright, the full-length Christmas CD by Mark and his Sweet Gingerbread gal Jessica Martin. It's a collection of twelve great tracks, from a swingin' romp through Mariah Carey's "All I Want For Christmas Is You" to the dancefloor-packing disco megamix of "A Marshmallow World". Mark & Jessica also offer a "Jingle Bells" that will sleigh you, the jazzily romantic "Snowbound", the merriest "Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas" you'll ever hear, plus Santas, glow worms, eggnog, and a couple of New Year numbers, including what the Pundette calls Mark's "perfect" "What Are You Doing New Year's Eve?"

~There's an hour's worth of great seasonal music on Making Spirits Bright, the full-length Christmas CD by Mark and his Sweet Gingerbread gal Jessica Martin. It's a collection of twelve great tracks, from a swingin' romp through Mariah Carey's "All I Want For Christmas Is You" to the dancefloor-packing disco megamix of "A Marshmallow World". Mark & Jessica also offer a "Jingle Bells" that will sleigh you, the jazzily romantic "Snowbound", the merriest "Have Yourself A Merry Little Christmas" you'll ever hear, plus Santas, glow worms, eggnog, and a couple of New Year numbers, including what the Pundette calls Mark's "perfect" "What Are You Doing New Year's Eve?"

All twelve songs from Making Spirits Bright are available for download at iTunes, Amazon and CD Baby. But don't forget you can also order the full CD in its attractive gatefold sleeve direct from the Steyn Store, where you'll also find many other musical offerings. And, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter your promotional code at checkout to enjoy special member pricing.