Kathy Shaidle is away this week, enduring, as most of you know, a pretty awful time. She and Arnie launched a fundraiser on Wednesday, which I'd planned to link to today, but they've reached their goal and shut up shop. I'm sure, however, that if you wanted to go full Wayne County and sneak something in after the deadline they would be pleased to accept. I had the privilege of spending a couple of afternoons with Kathy this week, and it was simultaneously unbearably sad and hugely enjoyable - because she is always great company, even in the worst of times.

As for our Saturday-night movie beat, it gives me no pleasure to fill in for Kathy in such circumstances, as you can probably tell from the following sentence:

Love Actually is crap actually. I say that in the spirit of the movie, which begins with clapped out rock geezer Bill Nighy recording his new single, a seasonal remake of "Love Is All Around" that doesn't even scan: "ChristMAS Is All Around". It is a cynical exercise on his part: he cheerfully tells his manager it's "crap", the disc-jockey of Radio Watford it's "crap", the listeners it's crap, Ant & Dec on the yoof TV show it's "crap", and everybody else that its' total crap. But the great British public takes the crapness to heart, and the cynical crap touches a chord.

If only the film were that good. Made in 2003, it is a cynical confection and, unlike Nighy and his Yuletide single, never transcends its cynicism - at least not for me: million of others love this picture and watch it every Yuletide. The framing device is droll - will Nighy's "ChristMAS Is All Around" be this year's Christmas Number One? (Which has been a big deal in the United Kingdom for half-a-century, as Tim Rice briefly touches on in this weekend's Mark Steyn Show). Mr Nighy, a great actor who's done Shakespeare and Chaucer, Chekhov and Rimbaud, manages to turn this thin gimmick into the part of a lifetime, and a splendid turn that is truly beloved. His is also the performance that vindicates the title, as Nighy abandons Elton's Christmas party to spend the night getting rat-arsed with his Scots manager.

That aside, the one thing this movie doesn't believe in is love. Or, at any rate, it doesn't trust love. The title comes from a speech by the incoming Prime Minister Hugh Grant. His line is that, for all the apparent hatred in the world, all you have to do is go to the arrivals hall at Heathrow and you'll see all kinds of people hugging each other: "Love actually is all around." He adds that, on the planes that crashed into the Twin Towers, he didn't think a lot of those final cellphone calls were about hate. Only love.

The dubious taste of a reference not just to 9/11 but to one of the most intimate details of 9/11 would be forgiven if the ensuing two-and-then-some hours justified Grant's thesis and the appropriation of the image. But love is not enough for writer/director Richard Curtis. He's constructed this film as a roundelay punctuated by Nighy's progress up the pop charts: lots of different characters, lots of different stories, all loosely connected. Usually that means some folks are young, some old, some rich, some poor, some worldly, some naïve, etc. But not in Curtisland. Boy-meets-girl won't do unless it's in some freakish novelty situation: the Prime Minister's in love with his below-stairs tea-lady; an English writer who can't speak Portuguese is in love with his Portuguese maid who can't speak English; two nude body-doubles on a movie set make chit-chat about the traffic as they mime oral sex, and then on their first proper date shyly end the evening with a peck on the cheek. This last couple (Martin Freeman and Joanna Page) are one of the more engaging romances, but the film accords them only a very bare minimum of screen time.

After Four Weddings And A Funeral, Notting Hill and Bridget Jones' Diary, this film makes you wonder whether Richard Curtis is fresh out of tricks. It plays like (to put in Curtis terms) a K-Tel greatest-hits compilation album. It's got one wedding, one funeral; one office party, one school concert; the usual glamourised London landscape, lit like Manhattan and traffic free; Hugh Grant being self-deprecatingly charming, Colin Firth being tentative; naff pop songs – Donny Osmond for the wedding, the Bay City Rollers for the funeral; a disquisition by Firth on "Silence Is Golden" by the Tremeloes to match Grant's evocation of "I Think I Love You" by the Partridge Family in Four Weddings...

One accepts the codes and conventions of Curtisland: the slightly snobbish classlessness, the compression of London into one hip village – here, everybody has a child, sibling, nephew or cousin at the same Wandsworth school. As is his wont, it's all moments and nothing to connect them, an endless parade of big set-pieces – the Portuguese maid strips off to retrieve the English writer's scattered manuscript from the pond – without the necessary building up to or unwinding therefrom. The wedding is a good example: up in the choir loft a chorus of "All You Need Is Love" begins, down below a full orchestra pops up from various sections of the congregation, the vicar high-fives the best man. It's cute in a generic way – we don't know the bride, groom or anybody else – but, when a film piles up this sort of stuff every five minutes, you mainly notice the excessive calculation and manipulation. Love Actually works so hard to be loveable, it's actually quite repellent.

By the time we get to the finales – the Prime Minister's unexpected appearance at the climax of the school concert, a ten-year old boy's frantic dash through Heathrow to the departure gate, a vast extended family of earthy Portuguese types accompanying the English writer through the streets to his wedding proposal – you can't help noticing that, at least professionally, Curtis has intimacy issues: for these characters, love is a performance that has to be played out in front of a vast audience of south London parents, airport security teams and South of France diners, and all to a horribly banal orchestral score by Craig Armstrong.

But, amazingly, as crude as these scenes are, they're not as bad as the requisite Curtisian leavening of the sweet with the bitter: mumsy Emma Thompson confronting straying hubby Alan Rickman. Miss Thompson is an actress of great subtlety, but Curtis is so unconfident of her skips he sticks her in frumpy baggy brown cardigans and floor-length shapeless grey skirts that practically scream "Go on, cheat on me!" It's as if he's forgotten how to write anything but the coarsest shorthand. Love Actually isn't in love with anyone except itself: it's like watching a practiced lounge lizard go through his repertoire. That's why Bill Nighy's wrinkly old rocker steals the picture: although he's just about the only member of the dramatis personae not actively looking for love, in a forest of over-mannered love scenes Nighy lurches through the movie with a cheerful indifference that makes his the only really honest character.

What I mainly remember as the years go by is the power imbalance: Almost every one of the alleged romances on which the film lingers is between a powerful man and his underling - Rickman and his sexpot secretary, Hugh Grant and the lowliest staffer, Colin Firth and his housekeeper. Even at the time, Curtis's view seemed a weirdly narrow view of human relations. With the benefit of hindsight, I checked to see whether Love Actually was one of Harvey Weinstein's masterpieces, but he was apparently busy with more obvious chick-flick Oscar bait that Christmas. In the Me-Too era we now know that beloved network anchormen have under-desk buttons to lock you in their offices, that PBS hosts think 25-year old interns at meetings enjoy seeing penises three times their age, that fashionable Manhattan restaurants have rape rooms, and that, when you clear out the sex fiends from NPR, there isn't a lot left on the schedule.

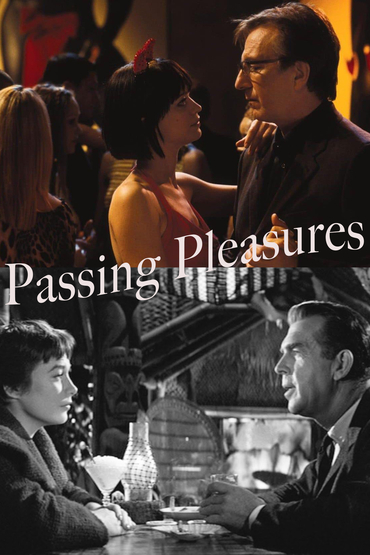

In the old days, successful men did marry their secretaries and housemaids, but not so much now, at least in America, when power-lawyers and political consultants contract intermarriage like medieval ducal houses. So I thought I'd round things out with a Christmas picture about sex and power in the workplace from an era with very different cultural mores (although certain aspects of the scene remain entirely unchanged over six decades: "everybody knew"). It was made by the ultimate Hollywood cynic Billy Wilder, but he's a piker compared to Richard Curtis. I'm not the biggest Billy Wilder fan, nor the biggest Jack Lemmon fan, nor Shirley MacLaine fan. But all three did some of their best work here. By the way, I am a huge Fred MacMurray fan and he is terrific in this.

The Apartment is a sad but true urban Christmas fable: there's no snow, just flu all month long; the office-party booze makes everyone mean and sour; the only sighting of le Père Noel is an aggressive off-duty department-store Santa chugging it down at a midtown bar; and the Christmas Eve climax is an attempted suicide. But that's what I love about The Apartment: its Wilderian cynicism is redeemed by one of the sweetest Christmas Day scenes in any movie. In his review of Rodgers & Hart's amoral Pal Joey, Brooks Atkinson wrote: "How can you draw sweet water from a foul well?" Well, The Apartment pulls it off, wonderfully.

Wilder got the idea after seeing Noël Coward and David Lean's Brief Encounter (1945) and finding himself wondering about the fellow who lends his flat to Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard for their illicit trysts. "The interesting character is the friend," Wilder said, "who returns to his home and finds the bed still warm, he who has no mistress." So Wilder and his screenwriting partner I A L Diamond came up with CC Baxter, a lowly cog in the corporate machine who advances to the heights of the 27th floor and a key to the executive washroom of his Madison Avenue office building - not by hard work but by loaning his apartment to various adulterous superiors.

Distracted by the traffic in the stairway, the clink of cocktail glasses, and the make-out music, Baxter's neighbors assume he's the swingingest cat in town. In fact, he's a lonely schlub freezing to death on a bench in Central Park waiting for that night's executive vice-president and whichever gal from the typing pool he's picked out for the evening to exhaust themselves and call it a day. Baxter has no moral qualms about facilitating adultery. He assumes it's what a go-getting guy has to do to get going. His misgivings arise only when he discovers that his boss, the predatory Mr Sheldrake, has turned his attention to Fran Kubelik. Miss Kubelik is an elevator operator in the building and the girl Baxter loves, although he hasn't told her yet, as their relationship to date has consisted of a few pleasantries exchanged as he rides her car up to the office each morning.

Fran is Shirley MacLaine at her early best: a rare American gamine in a Euro-dominated field (Leslie Caron, Audrey Hepburn), she's full of moon-faced vulnerability and unable to accept that her boss's interest is strictly carnal. As Sheldrake, Fred MacMurray is the apotheosis of Fifties corporate man, smooth, assured and ruthless as he exercises his droit du senior exec. As Baxter, Jack Lemmon's likeable nebbish shtick is captured in embryo, before it got out of control and degenerated into a collection of exhibitionist mannerisms. But Wilder put together one of the most perfectly cast ensembles in film history and it goes way beyond the leads: there's Edie Adams as Sheldrake's secretary, sitting in the outer office and watching this season's "new models pass by", and David White as Sheldrake's fellow corporate swordsman Eichelberger. (White's most memorable turn as corporate exec would come a couple of years later, as Darren's boss in "Bewitched". He died in 1990, two years after his son was killed in the terrorist takedown of Pan Am 103 over Lockerbie.)

Wilder and Diamond's script catches the argot of the day beautifully, not least in Mr Kirkeby's inability to get through a sentence without using the suffix "-wise" — situation-wise, business-wise, etc. The screenplay makes it a kind of corporate code — the Masonic handshake of the 27th floor — that the ambitious Baxter lapses into almost subconsciously. When Kirkeby thinks CC Baxter has actually snared the elevator operator, he congratulates him: "So you hit the jackpot, eh, kid? I mean, Kubelik-wise?"

But, Kubelik-wise, the jackpot is a long way off, and how loser boy gets there is forlorn and funny all at the same time. The Apartment is a comedy, but it catches the desperation of inconsequential people passed over by the holiday season. And so it is that Christmas-wise CC gets to spend the day with the recuperating Fran, who's dumped at his apartment after Sheldrake goes home for the holidays with the wife and kids. In Fran and CC's bedsit Christmas, there are no chestnuts roasting, but they do play gin rummy. Baxter's face is never happier than when he's straining spaghetti through his tennis racket and never more loving than when he innocently tucks in his sleeping elevator gal and heads away from the bed (with no Al Franken slumber-grabs). It may not be much of a Christmas, but it beats the previous year when he went to the zoo and had Christmas dinner at the automat.

A lot of it's the script, a lot of it's the chemistry between Lemmon and MacLaine. But, for whatever reason, The Apartment is one of the best, both Yuletide-wise and masterpiece-wise — oh, and uniforms-wise. I've never been much of a dress-up fetishist, but I do think Shirley MacLaine's elevator get-up is awfully cute. If anyone's minded to send me a specialty strippergram next birthday, that's my choice. (Last year there was a booking error and I wound up with the open-bathrobed Charlie Rose-alike Chippendale.)

~If you disagree with Steyn's movie columns and you're a member of The Mark Steyn Club, then feel free to have at him in the comments. Club membership isn't for everybody, but it helps keep all our content out there for everybody, in print, audio, video, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Saturday movie dates.

If you're in the mood for more seasonal, Mark will be launching our Christmas season of Tales for Our Time in the coming days.

Tales for Our Time is brought to you by The Mark Steyn Club. What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's an Audio Book of the Month Club - or, if you prefer, a radio-serial club. It's also a discussion group of lively people around the world on the great questions of our time. It's a video poetry and live music club. And, if you've got some kith or kin who might like the sound of all that and more, for this holiday season only we have a special Christmas Gift Membership that includes a welcome gift of favorite Tales for Our Time. More details here.

And don't forget, over at the Steyn store, there are bargains galore in our Steynamite Christmas Specials.