For various reasons, the combination of the words "honey trap" and "Eric Swalwell" is inherently risible - although, as I reminded Tucker's viewers, he did get as far as the House Intelligence Committee and a presidential run, so it was not a complete waste of Fang Fang's undoubted expertise. And, from Swalwell's point of view, it could have gone worse. This is from the expanded eBook edition of Mark Steyn's Passing Parade:

The Cold War "honey trap" somehow managed to outlast the Cold War and endures even in a hypersexualized age. Hence the highly graphic video posted to the Internet by the KGB's successors at the FSB, "The Adventures Of Mr Hudson In Russia." Mr Hudson was in Russia to serve as Britain's deputy consul-general in Ekaterinburg, but his starring role opposite and under two local hookers brought an end to his tour of booty, er, duty: one portly bespectacled Foreign Office chappie, with his dressing gown hanging open, quaffing champagne with a pair of naked Urals slappers going through the motions with all the flair of the mechanical hare at an East End greyhound track.

How quaint it sounds: the "honey trap". But it can be a lonely life out there on the diplomatic circuit, and. for an enterprising intelligence agency, the wallflower at the embassy ball is still a reliable way to access your enemy's secrets. As it happens, Mr. Hudson's career self-detonated only a few days after the death of one of the most famous honey traps of the post-war era, the Chinese opera singer Shi Pei Pu.

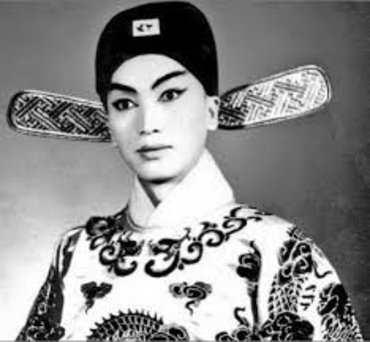

Shi was a he, although for a while that wasn't entirely clear. As a famous headline in Le Monde wondered: "Espion ou espionne?" Spy or spy-ette? James Bond or Pussy Galore? When Bernard Boursicot first saw him across a crowded room at some enchanted diplomatic evening in Beijing in 1964, the espion was certainly a he - a slip of a lad in his mid-twenties but already an accomplished singer and actor, and socially assured. By contrast, M Boursicot was the French Embassy's accountant, a 20-year-old schnook from the wrong side of the tracks whom the career diplomats already figured for a loser. The girls in the typing pool called him Bouricot - "Donkey" - and not as a compliment. He was a virgin, lonely and longing for love. And there, at the centre of attention, was the glamorous young Chinaman, if that's the word.

The categorization was complicated by Shi's profession, for in Chinese opera the males can play female roles. At a subsequent meeting, the singer told him the plot of one of his great stage triumphs, The Story of the Butterfly. Once upon a time, there was a beautiful girl who longed to study at one of the imperial schools. She is a gifted pupil, but, alas, in China girls were forbidden to attend school. So she makes a secret plan with her brother, who dislikes class and does poorly in his lessons. They will swap clothes and she will go to the imperial school in his stead...

A few days later, Shi and M Boursicot met again, and took a walk in a courtyard in the Forbidden City. "Look at my hands, look at my face," the opera singer told the diplomat. "That story of the butterfly - it is my story, too." For Shi was born a she, to parents who already had two daughters. And so they raised her as a boy.

But she's not. She's the girl he's been waiting for. Friend, lover, wife.

More days go by. They're at Boursicot's apartment, and Shi strips down to her panties ...

Years later, at the London premiere of David Henry Hwang's famous play on the subject, M. Butterfly, I remember standing outside the Shaftesbury Theatre on a balmy spring evening as the first-night crowd spent intermission discussing not B D Wong's or Anthony Hopkins' performances nor the dialogue or staging, but rather the, ah, mechanics. The gay theatre critics earnestly inquired of the straight theatre critics whether any man could possibly confuse the sensation of anal with vaginal penetration, while the dour feminist critics rolled their eyes and the token bisexual critic flaunted his own comprehensive expertise.

But, aside from a few schoolboy fumblings in the dorm, Bernard Boursicot knew very little about the basics of boy-meets-girl—and certainly a lot less than those louche West End first-nighters. Whether because he had a thespian's eye for set design or because his masters in Chinese intelligence supplied him with all the right props, Shi didn't skimp on the details. After the consummation of their love, M Boursicot went to the bathroom and, upon his return, noticed virginal blood on Shi's upper thigh. It required little effort to persuade the embassy accountant that "she" was pregnant with their child.

In 1983, when diplomat and spy were arrested in Paris, they were both taken to Fresnes, a male prison, notwithstanding Shi's insistence that she was a woman. The doctors were told to determine whether Shi had or had ever had female genitalia. Answer: no. As to the genitals he was packing, he told Joyce Wadler, author of the book Liaison: The True Story Of The M. Butterfly Affair, that he stood up and demonstrated to the prison medical staff how he could retract his penis and testicles into his body cavity and, by holding his legs together, make his scrotum appear to be not unlike vaginal labia. "Of course, one could not look too closely. It was only illusion," wrote Ms Wadler. "But 90 per cent of love, even a man of science will volunteer, is illusion."

The French Ministry of Justice was not so philosophical. They announced that the new Mata Hari was, in fact, Master Hari - a man. "It's unbelievable!" roared Boursicot, lying on his cell bunk and raging at the radio. "It's a lie!"

It was the Broadway producer Stuart Ostrow who thought the story had theatrical potential and commissioned Hwang to write it. You can see why. It's not just Cold War espionage. To the Communists, the Shi trap was the perfect subversion of one of the most enduring imperialist narratives of east and west. You don't have to be a Marxist deconstructionist to see Madam Butterfly in its multiple incarnations as a tale of not merely sexual but cultural exploitation. Pinkerton has the affair, Butterfly has the baby. And so it goes, through every telling, from short story to play to opera to pop song:

The moon and I know that he be faithful

I know he'll come to me by and by

But if he won't come back

I'll never sigh or cry

I just must die

Poor Butterfly....

The template was established in Butterfly's predecessor, Pierre Loti's autobiographical novel Madame Chrysanthemum. "Pierre", a French naval officer stationed at Nagasaki in 1885, relieves the burden of his posting by entering into a temporary "marriage". Nine days after Puccini's opera of Madam Butterfly opened at La Scala, the Russo-Japanese war began. "I believe," wrote William Schwartz in The Imaginative Interpretation Of The Far East In Modern French Literature, "that the contempt for the Japanese expressed in Loti's books in some measure influenced the Russians to refuse Japan's requests and led to the war of 1904." Six decades later, the Chinese figured there was enough potency in the Butterfly myth to make it work for the Cold War. This time it's the westerner who's suckered, with the baby as bait. As the Frenchman discovered 16 years later, the boy was not Boursicot's, nor Shi's, but a Chinese Uighur Muslim sold by her mum as a service to the People's Republic.

In John Luther Long's original short story (published in Century Magazine in 1898), Cio-Cio-San reaches her decision, picks up her father's sword, and reads the inscription:

To die with Honour,

When one can no longer

live with Honour.

And then "she placed the point of the weapon at that nearly nerveless spot in the neck known to every Japanese, and began to press it slowly inward. She could not help a little gasp at the first incision. But presently she could feel the blood finding its way down her neck. It divided on her shoulder, the larger stream going down her bosom. In a moment she could see it making its way daintily between her breasts. It began to congeal there ..."

A laughingstock throughout France, Bernard Boursicot also decided he could no longer live with Honour. He took the knife French prisoners are issued for meals - too short and blunt for purposes of suicide, but good enough to peel away the plastic from his disposable razor. And then, having liberated the blade, he drew it across his throat until it fell from his fingers. The ultimate plot inversion: his Butterfly will live, and he will die.

But it's harder in prison than on an opera stage. They found him, they saved him, and today he lives in a French nursing home. Despite his best efforts, his Butterfly, like all the others, predeceased the leading man. "The plate is clean now," he said on being informed of Shi's death. "I am free."

~excerpted from the expanded eBook edition of Mark Steyn's Passing Parade, which is available here and at other retailers.

If you're a member of The Mark Steyn Club, feel free to disagree in the comments section - but please do stay on topic and be respectful of your fellow members; disrespect and outright contempt should be reserved for Mark personally. For more on the Steyn Club, please click here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership, which makes a great Christmas present.

Mark will be back on Friday for the weekend edition of The Mark Steyn Show.