Our P G Wodehouse tale of graft and grime in the New York of 1910-ish is hurtling (not quite le mot juste) toward its conclusion. The theme music for the show is a very obscure piece called "The Ragtime Restaurant", by Wodehouse's longtime friend and songwriting partner Jerome Kern. We've done a whole show on Kern & Wodehouse songs (which are a particular pleasure of mine), but I thought I'd treat myself to one more - not written with Plum, but very much in the air when Psmith, Journalist was published in 1915. In fact, it was pretty much the biggest song of the day 105 years ago.

I love early Kern, so this one's for me. But in a broader sense it's where this entire Song of the Week business of ours really begins. When this feature started almost fifteen years ago, our Song of the Week #1 was "San Francisco" - to mark the centenary of the 1906 earthquake. But, if I'd been thinking about a Number One song in more profound terms, our Number One song would have been this one - because this week's song was really the Number One song for an entire school of songs.

As Mel Tormé put it, when Jerome Kern composed this melody, he "invented the popular song". If your idea of a popular song is "Call Me Maybe" or "Blurred Lines" or even "The Tennessee Waltz", Tormé's claim may seem a bit of a stretch. But it's not unreasonable to suggest that with this tune Kern invented what we now call the American Songbook - standards that endure across the decades and can be sung and played in almost any style. It is, thus, the Number One Song, the first and most influential entry in that American Songbook, the Number One song that influenced so many of the others that followed - "Summertime" (SOTW #10), "As Time Goes By" (SOTW #26), "Night and Day", "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes", "My Funny Valentine", "The Way You Look Tonight", "I'll Be Seeing You", "Almost Like Being in Love", "Till There Was You", "Send in the Clowns", "Windmills of Your Mind", and dozens more of those we've featured over the years. This song is the daddy of them all.

It was introduced into the world just over a century ago - on August 24th, 1914, at the Knickerbocker Theatre in New York. That's to say, it's a love song one hundred and six years old, and still in circulation. Here's Elvis Costello's take with Marian McPartland:

And, for a different point of view, here's Dinah Washington swingin' with Quincy Jones:

By way of a little bit of scene-setting, consider the broader musical context of 1914: Most of the big songs of the year are forgotten - "Can't You Hear Me Callin', Caroline?", "The Darktown Poker Club", "Who Paid The Rent For Mrs Rip Van Winkle?" A handful of them linger in memory - "When You Wore A Tulip", "The Aba Daba Honeymoon", Irving Berlin's contrapuntal ragtime novelty "Play A Simple Melody" - but they're fragrant of the era: When they're sung today, it's to evoke yesterday. That's true of the big British hits of 1914 - one of the last enduring music hall novelties, "Burlington Bertie From Bow", and the song to which the Empire marched off to the slaughter of the trenches, "Keep The Home Fires Burning". And, to a lesser degree, that's also true of the other undisputed masterpiece of 1914, W C Handy's "St Louis Blues", which is still in the repertoire musically but can't really be said to be of contemporary sensibility lyrically: If you recall the Ferguson effect or those gun-owners defending their property, you'll know that 21st century St Louis blues are of a different order, as is what happens when de ev'nin' sun goes down.

The theatre of 1914 is even more cobwebbed. European operetta was still a going concern and, until the Great War intervened, sent its biggest hits winging west to London and New York. The heavyweight Broadway composers, like Victor Herbert, wrote in a local variant of the operetta idiom. The more raucous lads interrupted barely coherent comic plots with notey cluttered verse-heavy story songs with perfunctory choruses. The notion of Broadway as the source of the greatest intimate conversational love songs ever composed had never occurred to anyone ...until Herbert Reynolds and Jerome Kern sat down and wrote:

And when I told them

How beautiful you are

They Didn't Believe Me

They Didn't Believe Me...

Years ago, in his biography of Kern, Gerald Bordman wrote that "They Didn't Believe Me" was the first love ballad in 4/4 time to be the principal song in a Broadway musical. I've certainly never found any earlier title that seriously challenges that claim. And so it happened that the first great American theatre ballad was written for a British musical. "They Didn't Believe Me" was introduced in the Broadway version of a show called The Girl from Utah, a West End hit from the previous year, 1913. The Girl from Utah is about a girl from Utah - on the lam from a wealthy Mormon who wants to make her his latest wife. She winds up in London, where a debonair actor saves her from her polygamous suitor. So far, so typical. The plot, such as it was, was the work of James T Tanner, who wrote some of the biggest West End hits of the day. The music was by Paul Rubens, who'd contributed additional songs to Florodora, the 1899 London hit that became a global phenomenon - and whose "Tell Me, Pretty Maiden (are there any more at home like you?)" was the acme of theatrical love songs in the pre-Kern era. There were additional tunes by Sidney Jones, composer of The Geisha, and words by Adrian Ross, who'd written the English lyrics for The Merry Widow, and Percy Greenbank, the title of whose 1903 hit The Earl and the Girl could stand for an entire genre. If you've never heard of any of these fellows, it's because Kern and the generation he inspired - Porter, Gershwin, Rodgers - helped put Messrs Rubens, Jones, Ross and Greenbank out of work. Mr Greenbank lived until 1968, which means all those Edwardian musical comedies are still in copyright, if only anyone wanted to perform them.

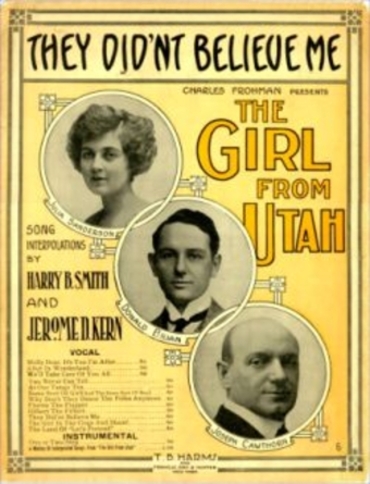

The Girl from Utah was a hit in London, and the American producer Charles Frohman decided to bring it to New York. But he thought the First Act was, musically, a little weak, so he asked Jerome Kern and the prolific Harry B Smith to write a handful of new songs for the Broadway production. Kern and Smith wrote four of them, and they're fine - the wistful "You Never Can Tell", the almost swinging "Same Sort Of Girl", a rollicking "Why Don't They Dance the Polka?", and an otherworldly number that opened and closed the show, "Land of Let's Pretend". But for the fifth song he had a number that he thought would work great. And so on August 24th 1914 at the Knickerbocker Theatre it fell to Julia Sanderson, as the eponymous Utah girl, and Donald Brian, as her British suitor "Sandy Blair", to introduce the number Dinah Washington and Elvis Costello would sing a half-century and near-century later:

Your lips, your eyes, your curly hair

Are in a class beyond compare

You're the loveliest girl

That one could see...

That's the text as sung in the show, by the way: the "curly hair" quickly became "your cheeks, your hair", so as to apply to lanker-coiffed objects of one's desire. The lyricist, Herbert Reynolds, thought the song would be great for Jolson, and it's not hard to picture him, in blackface, down on one knee, wringing every lachrymose line into the orchestra pit. But Kern figured it would be better suited to The Girl from Utah, and he prevailed.

I've earned a shilling as a critic at various times over the years and been very grateful for it, but I have a low regard for the craft generally and cases like The Girl from Utah are why. You look up the first-night reviews to see what the gentlemen of the press made of the song, and they didn't notice it. They had no idea that, never mind a century on, a mere decade later the only thing about The Girl from Utah anyone would know or care about would be "They Didn't Believe Me". The New York Times drama critic didn't mention it, nor did The New York Sun's man. The New York Tribune's reviewer did notice it and pronounced it "decidedly attractive", but didn't recognize it as a Kern tune. As he noted:

One isn't informed by consulting the programme just what songs Jerome Kern added to the score, but one hazards a guess at 'Gilbert the Filbert,' sung by Donald Brian in the first act, and 'Florrie the Flapper,' sung with delightful unction by Joseph Cawthorn. These two, despite the English slang terms employed for 'stage door Johnnie' and 'chorus girl,' sound like Mr. Kern's work.

Er, no. Both are quintessentially English. "Gilbert The Filbert", an interpolated London number, was the signature song of the West End star Basil Hallam, whose final moments at the front in 1916 were poignantly described by Rudyard Kipling in his account of The Irish Guards in the Great War:

On a windy Sunday evening at Couin, in the valley north of Bus-les-Artois, the men saw an observation-balloon, tethered near their bivouacs, break loose while being hauled down. It drifted towards the enemy line... Soon after, something black, which had been hanging below the basket, detached itself and fell some three thousand feet. We heard later that it was Captain Radford (Basil Hallam). His parachute apparently caught in the rigging and in some way he slipped out of the belt which attached him to it. He fell near Brigade Headquarters. Of those who watched, there was not one that had not seen him at the 'Halls' in the immensely remote days of 'Gilbert the Filbert, the Colonel of the Nuts'.

That was not a Kern song.

Everyone other than the critics seemed to get "They Didn't Believe Me". It's said that at the end of that first performance by Miss Sanderson and Mr Brian the audience was singing along. Britain's Chancellor of the Exchequer (and future Prime Minister) was among those smitten: David Lloyd George called it "the most haunting and inspiring melody I have ever heard". It certainly inspired a sixteen-year old aspiring musician called George Gershwin. He was attending his aunt's wedding at the Grand Central Hotel in New York when the band began to play "They Didn't Believe Me". George was astonished. "Who wrote that?" he asked. When he heard the answer, it finally convinced him that he should become a composer, too - and not for Tin Pan Alley but, like Kern, for the stage. A couple of years later, he was working as a rehearsal pianist on the Bolton, Wodehouse & Kern show Miss 1917.

We've featured several Kern songs over the years at Song of the Week - "Smoke Gets In Your Eyes", "I Won't Dance", "Pick Yourself Up", "The Way You Look Tonight", "A Fine Romance"... It's a glorious body of work. Yet you can understand young Gershwin's astonishment at learning the identity of the man who wrote "They Didn't Believe Me". Kern had been writing for the London and New York stage since 1905's "How'd You Like To Spoon With Me?" - and nothing from that first decade of patter songs and novelty numbers gave any indication that he had anything like "They Didn't Believe Me" inside him. Years later, Richard Rodgers described Kern as having one foot in the Old World, one in the New. I'm not sure even that was true pre-1914: he wrote like a London composer of Edwardian "Gaiety shows".

The practice in those days was to have long verses to accommodate lyric narratives and short sixteen-bar choruses. "They Didn't Believe Me" marks the point at which the chorus expanded to become the meat of the song and the verse shrank to become little more than, as Frank Loesser liked to say, "Tweedle-tweedle-dee, tweedle-tweedle-dee, and that's why I sing..." "They Didn't Believe Me" has a modern - or timeless - 32-bar chorus and a verse that seems to come from a different musical universe. As the musicologist Alec Wilder wrote:

Outside of its un-Viennese freshness, there are several interesting oddities about this song. The verse has a trace of musical character, as had few of the many verses of Kern's earlier songs. Yet it still seems to have been written at another time than the chorus, so much so that the chorus comes as a total surprise. It is hard to consider them as part of the same musical experience, in spite of the adroitness with which the verse leads into the chorus.

Wilder's right about the verse sounding "written at another time". The chorus seems like an organic outpouring of romantic feeling, whereas the verse is built on one of those two-note tumty-tumty seesaws that plants it right back in the era of cutesie musical-comedy couples sitting on a park bench or a sofa and describing love rather than expressing it:

Got the cutest little way

Like to watch you all the day

And it certainly seems fine

Just to think that you'll be mine...

I agree with Alec Wilder on that verse, and so do 99.99 per cent of singers who've sung the song in the last century and decline to bother with the verse, even if they're aware it exists. By comparison with later Kern ballads ("All The Things You Are"), the chorus is not particularly harmonically sophisticated. As a general rule, the stronger Kern's melodies the less he was inclined to risk muddling them with harmonic complications - and "They Didn't Believe Me" is a classic one-finger melody that Wilder declared to be "as natural as walking":

I can't conceive how the alteration of a single note could do other than harm the song. It is evocative, tender, strong, shapely, and, like all good creations which require time for their expression, has a beginning, middle, and end.

But that "natural as walking" feel requires a certain skill. The second eight bars functions as a kind of premature middle-eight, and in the thirteenth bar he slips in a D natural - "You're the loveliest girl" - that's not in the A-flat scale, but is critical to set up the D natural necessary to the harmony in the following bar. In terms of structure and progression, Kern is really inventing a form here. The 32-bar AABA 4/4 ballad did not really exist. Romance was conducted in three-quarter time, whether the Merry Widow waltz or "(Casey would waltz with the strawberry blonde) And The Band Played On". With this song, Kern made 4/4 the beat of the heart.

As for the lyric, it's ...okay. It's charming and tender, and, set to those notes, irresistible, which is more than can be said for other Broadway ballads of the period. If the name of its author, Herbert Reynolds, doesn't ring any bells, well, Herbert Reynolds was a pseudonym for M E Rourke. If M E Rourke doesn't ring any bells, well, he was born Michael Elder Rourke in Manchester, England in 1867. He went to America, set up as a press agent and wrote his first song with Kern in 1906. And of the hundreds of lyrics he wrote, this is the only one that's lasted. Here's the really delightful bit:

And when I tell them

(And I'm certainly goin' to tell them)

That you're the boy

Whose wife one day I'll be...

That "certainly" is set to the only triplet in the entire tune, in the 19th bar. When I first heard the number, round about the age George Gershwin was when he did, I thought it was a marvelous effect, and a perfect example of the craftsmanship of popular song, of two distinct arts - words and music - merging to create a third. I had no idea whether Kern wrote the triplet to accommodate Reynolds' three-syllable word, or Reynolds fitted the three-syllable word to highlight Kern's lovely triplet, but it's impossible to hear the melody without recalling the lyric, or to see the words without evoking the music.

And then years later I bought a copy of the original sheet music. And what it actually says is:

And when I tell them

(And I cert'nly am goin' to tell them)...

What a clunker! Who can sing "cert'nly am" to that triplet and spring clear of the "m" in time to make the "g" of "goin'", which itself has to be sung in one syllable on a single note? Was it Kern butchering Reynolds' tri-syllable? Or Reynolds cluttering up Kern's triplet? Or a careless copyist at the publishers? That kind of thing was not uncommon to Broadway lyricists of Herbert Reynolds' generation, and we should be grateful for whoever the singer was who, shortly thereafter, amended it, very charmingly, to "I'm certainly goin' to tell them". Which adds another bizarre distinction to the song: The first great American theatre ballad was written for a British musical, and the highlight of its lyric may be no more than a correction of a hamfisted stinkeroo in the actual text.

There were a few other changes over the years: some singers preferred "wonderful" to "beautiful"; some opted for the past tense - "and when I told them... they didn't believe" - over "they'll never believe me"; some favored "the man whose wife" over "the boy whose girl..." But these minor amendments emphasized what Kern and Reynolds had wrought: a bewitching tune with a lyric idea muscular enough to survive whatever interpretative fancies a singer might bring to it.

It wasn't written as a war song, but, especially for its first British listeners, it quickly became one. If you've ever seen Joan Littlewood's Oh, What A Lovely War on stage or screen, you'll be familiar with the soldiers' parody she includes:

And when they ask us

How dangerous it was

We never will tell them

We never will tell them

How we fought in some café

With wild women night and day

'Twas the wonderfulest war you ever knew

And when they ask us

And they're certainly goin' to ask us

Why on our chests

We do not wear the Croix de Guerre

We never will tell them

We never will tell them

There was a front, but damned if we knew where.

And, if you believe that, you'll believe anything. In the programme, Miss Littlewood listed the author of these words as "unknown". Years later, Robert Kimball was going through Cole Porter's miscellaneous notes and manuscripts, and discovered his draft of the above. He was serving with the French Foreign Legion at the time, which sounds like a joke, but in fact the Legion lists him as one of its veterans. He was a young man, unknown on Broadway or Tin Alley, but, as much as George Gershwin at his aunt's wedding, he too fell under the spell of "They Didn't Believe Me".

Kern himself understood that with this tune he'd taken his craft to new heights. He was proud of "They Didn't Believe Me": A decade later, in his Second Act finale for a forgotten London show called The Beauty Prize, for a moment in which a character tells a lie, Kern slips in a sly quotation from "They Didn't Believe Me". From that first performance at the Knickerbocker one hundred years ago this week, it never went away. In the splashy all-star Kern biopic, Dinah Shore sang it, and then came Sinatra and Streisand, and Leontyne Price and Stan Kenton and Mario Lanza and Marvin Gaye and Artie Shaw, Harry Belafonte, Charlie Parker, Julie London, Count Basie...

But more than that the young Gershwin and Rodgers wrote their own 4/4 conversational love songs because "They Didn't Believe Me" had made such songs possible. A single song became the template for the Broadway ballad until the Seventies and Eighties ...and beyond Broadway for pop song romance until rock'n'roll came along. Upon hearing "They Didn't Believe Me", Broadway's operetta king Victor Herbert is supposed to have said: "That man will one day inherit my own mantle." He didn't realize that, with that song, Kern had already swiped his mantle - and set popular music on a new path:

And when I tell them

And I'm certainly goin' to tell them

That I'm the girl

Whose boy one day you'll be

They'll never believe me

They'll never believe me

That from this great big world you've chosen me.

~Many of Mark's most popular Song of the Week essays are included in his book A Song For The Season, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the Steyn store. If you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter your special promotional code at checkout to receive even more savings on that and over forty books, CDs and other products.

If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Ted Nugent, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Paul Simon, Lulu, Tim Rice and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and we also have a special Gift Membership.

Our Netflix-style tile-format archives for Tales for Our Time and Steyn's Sunday Poems have proved so popular with listeners and viewers that we've done the same for our musical features merely to provide some mellifluous diversions in the Land of Lockdown. Just click here, and you'll find easy-to-access live performances by everyone from Herman's Hermits to Liza Minnelli; Mark's interviews with Chuck Berry, Leonard Bernstein and Bananarama (just to riffle through the Bs); and audio documentaries on P G Wodehouse's lyrics, John Barry's Bond themes, sunshine songs from the Sunshine State, and much more. We'll be adding to the archive in the months ahead, but, even as it is, we hope you'll find the new SteynOnline music home page a welcome respite from looting, lockdown and 'lections.

If you're a Mark Steyn Club member and you're cert'nly goin' to tell us what's wrong with the above column, feel free to let rip in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page.