This last day of January has been one of those sunny but frigidly cold days in my corner of northern New England. So, when I stepped outside this morning, a fragment of lyric burst into my head and out of my mouth:

Nous filons sur la neige blanche

En ce beau jour de dimanche

À travers les sapins verts

C'est l'hiver, c'est l'hiver, c'est l'hiver...

Which means, more or less:

We're running on white snow

On this beautiful Sunday

Through the green fir trees

It's winter, it's winter, it's winter...

Doesn't ring any bells? Well, here's one of the nicest guys in Quebec showbiz, the late Pierre Lalonde:

"C'est l'hiver, c'est l'hiver, c'est l'hiver" reminds us that "Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!" is not a Christmas song at all, but a winter song more appropriate to late January/early February: It's "Baby, It's Cold Outside" without all the snowflake-triggering "Say, what's in this drink?" stuff. By coincidence, the very first recording of "Let It Snow!" hit Number One on the Billboard chart exactly three-quarters of a century ago, January 26th 1946, and stayed there till March - in other words, the perfect season for a very wintry song:

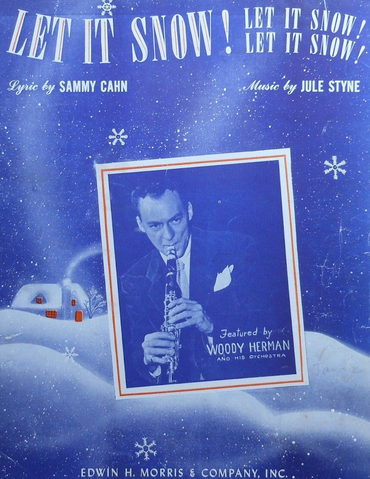

I yield to no one in my fondness for Vaughn Monroe, but I never feel he quite wrung the full juice out of that song. Of those first recordings, I have a mild preference for Woody Herman, bandleader and on this occasion also vocalist:

The men who wrote it are no strangers to these parts: Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn. Styne was a blockbuster Broadway composer of the post-war era - Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Gypsy, Funny Girl - and Cahn wrote the lyrics that re-defined the post-bobby-sox Sinatra as a ring-a-ding-ding swinger: "The Tender Trap", "Come Fly with Me", "My Kind of Town"... But even for songwriters that successful, a lasting seasonal hit is an insurance policy that never stops paying out the "Yuletide gravy", as Variety called it.

It didn't seem that smart a move in July 1945. Styne & Cahn were sitting in the offices of the Edwin Morris music publishing company on what Sammy told me was "one of the hottest days in the history of Los Angeles". That being so, he continued, "I wanted to go to the beach and cool off. But Jule said, 'Let's go write a winter song.'"

Sometimes it pays to be counter-intuitive: The following winter, on the chilliest of days, Styne & Cahn wrote "The Things We Did Last Summer".

I knew Jule Styne somewhat, and Sammy Cahn rather better: He was very generous to me, and opened a lot of doors. The first time I met Styne was at his office up the dingy stage-door stairs above the Mark Hellinger Theatre on Broadway. I noticed he wore a gold identity bracelet, and he showed me the inscription on the inside: "To Jule, who knew me when, Frankie" - a gift from Sinatra delivered to a bleary Styne by a courier from Cartier's the morning after the singer's spectacular solo debut at the Paramount Theatre in 1942.

He wore it for the next half-century. I remember it shaking when he waved his arms around and yelled, to make some point or other. He was a great yeller. He yelled at Jerome Robbins and Ethel Merman on Gypsy, he yelled at Streisand at Funny Girl. He yelled at Sinatra, which would cause occasional half-decade ruptures in their relationship. And, even when he wasn't yelling, his mind tumbled along faster than the words could keep up, so that his speech often omitted key verbs and nouns. His lyricists on "The Party's Over" and "Make Someone Happy", Betty Comden and Adolph Green, considered it a language all its own: Stynese. I had a radio producer who hated it whenever I brought him an interview with Jule Styne: Most radio editing involves removing extraneous words. With a Styne tape, half the essential words came pre-removed, as an ever more emphatic composer galloped on to his next big point, skipping two out of every five words before concluding triumphantly (as he once did to me after a complicated effusion on arrangers): "So them becoming that didn't become that!"

Styne never wasted his time with false modesty - in the Seventies, he announced he was America's greatest living composer - but his ego was so lightly worn it was rather endearing. Besides, people who need people are the luckiest people in the world, and Styne never forgot which people composers need. "I've been very fortunate in having my songs sung by the greatest male singer and the greatest female singer," he said, referring to his former flatmate (Sinatra) and a funny girl he helped make a star (Streisand). And as he was at pains to emphasize: "Without the rendition there is no song."

He never set out to write music. He was a Londoner, a poor boy born Julius Stein, though he seems never to have been called anything but "Julie". He was a child impressionist on the London stage before the First World War. At the Hippodrome, he got to do his Harry Lauder routine before Sir Harry himself. After sitting through young Julie's renditions of "She's My Daisy" and "Roamin' in the Gloamin'", the great Scot gave him some advice: "When you do impressions, you're never anyone in your own right. Do something of your own. Learn the piano or something." By the time the family moved to Chicago, the impressionist had become a pianist.

Sammy Cahn, on the other hand, was a New Yorker, younger than Jule, and a kid in a hurry. He'd worked as a freight-elevator operator and a movie usher and played the violin in a theatre pit. Then he'd gotten a job writing special material for the great Jimmie Lunceford band, and after that formed a songwriting team with Saul Chaplin. But Cahn & Chaplin had split up, and in 1941 Sammy was on his uppers. He was in Hollywood, but out of work, and padding the streets with nothing to do. One day he got a call out of the blue from Cy Feuer (later the producer of Guys & Dolls, but then a studio chief at Republic) asking if he'd like to do a picture with Jule Styne. Cahn had never heard of Styne, but he was in no position to be picky. "Right now I'd do a picture with Hitler," said Sammy.

Unlike the big studios, Republic wasn't exactly known for its music. But Sammy was introduced to Jule and, as all lyricists do, he asked him what he'd got. Styne sat down and played a tune from start to finish.

"Play it again," said Cahn. "Slower." So Styne did.

"Slower." So Styne played it even slower.

And Cahn said, "I've heard that song before."

"What are you, a tune detective?" said Styne, resenting the accusation of plagiarism.

Sammy explained that he meant it as a title not a copyright suit, and expanded on the theme:

It seems to me I've Heard That Song Before

It's from an old familiar score

I know it well, that melody...

And he had his theme, in every sense:

It's funny how a theme

Recalls a favorite dream

A dream that brought you so close to meI know each word

Because I've Heard That Song Before...

Sammy Cahn had a great facility for the structure of a tune and for underlining it very unobtrusively – the internal rhyme of "well" with "mel-ody", and then "word" with "heard". Those are minor details that nevertheless help make a song memorable and singable.

Republic pronounced themselves satisfied with the number and gave it to Bing's brother Bob Crosby and his band for Youth on Parade. And that was that. Jule Styne hadn't terribly cared for Sammy Cahn. He was looking for something classier in a lyricist, and he found Sammy a bit uncouth, too much the pushy New York wise-guy on the make. Which always amused me: Most writing teams bicker and squabble because they're temperamental opposites (Gilbert & Sullivan, Rodgers & Hart, Cy Coleman & Carolyn Leigh), but Styne and Cahn were in a certain sense too similar. There are songwriters who come from the Lower East Side and fit right in swanning about with Cole Porter and Lady Mountbatten. But there are others who never quite smooth off the rougher edges. Styne was a diminutive ball of energy, and Cahn looked like the shnook accountant, and Hollywood encouraged their worst inclinations. Styne was briefly Sinatra's flatmate, and Sammy ran with Frank to the end of his days: as Sinatra did, Styne liked to gamble, although generally disastrously; like Sinatra, Cahn was wont to womanize, although I never found accounts of his Frank-scale conquests entirely persuasive. But in 1942 Jule was seeking a poet, a man of letters, urbane and upscale - and Sammy reminded him too much of where he'd come from.

So he moved on to other lyricists, such as Kim Gannon. One day, back padding the streets, Cahn bumped into Gannon, who asked: "How did you like working with Jule Styne?"

"I liked it fine," said Sammy.

"Did you write a song about a song with Styne?"

"Yeah," replied Cahn, "I wrote a song about a song, and I think it's one of the best lyrics I've ever written."

"Maybe you think it's the best lyric," said Gannon. "Styne thinks it's the worst lyric he ever heard."

There would be other "worst lyrics he ever heard" in the decades ahead: It was something of a competitive category with Jule. But right now it was Sammy's that held the title.

And that's where things would have stayed were it not for the intercession of Big Sam Weiss, a musician turned song-plugger, and allegedly, on the night Sinatra slugged columnist Lee Mortimer, the guy who held the newspaperman down so Frankie could land one on him. Big Sam led a hectic life, but he'd heard "I've Heard That Song Before" and he loved it. And he managed to get it to the bandleader Harry James. There was just one problem. At the stroke of midnight on July 31st 1942 the American Federation of Musicians was supposed to begin a strike against the recording companies over a royalty dispute. The James band went into the studio on that very last day, and "I've Heard That Song Before" was the very last number to be professionally recorded before the musicians' union shut down the pop biz. Henceforth all songs would be songs you'd heard before because there would be nothing new for two years - the longest ever strike in the entertainment business.

So the last new record was "I've Heard That Song Before". Three-quarters of a century later, it still sounds great, from the opening figure built around that foot-stamping figure to Harry James' trumpet solo to Helen Forrest's terrific vocal:

If you've watched our occasional video Songs of the Week or listened to our weekly audio Songs of the Week, you'll know that we begin with a short musical intro that Kevin Amos and the band have been playing for us for a decade or so now, just a few bars and, indeed, so few you may not recognize the tune. But it is, in fact, "I've Heard That Song Before". Because it's the perfect theme tune for this series:

It seems to me I've Heard That Song Before

It's from an old familiar score

I know it well that melody...

Everyone knew it well in the spring of 1943. It was Number One for thirteen weeks - an all-time record that held for over half a century until 1995, when Mariah Carey and Boyz II Men pipped Helen and Harry by three weeks.

"Sammy loved that big band sound," Jule said to me, explaining to me why they eventually broke up, "and that's all he wanted to write." But sometimes it all comes together, and that song is one of a dozen or so that sum up the era.

Its success reconciled Jule Styne to the lyric. He heard Harry James on the radio, and picked up the phone. "Hey, Sammy, I think we ought to write some more songs." And a great songwriting team was on its way.

Cahn liked to write fast, and sometimes you wish he'd taken a little more time. But, when the muse descended in that express elevator, it was worth the forty-five-second wait. so on that broiling hot California day in July 1945 Sammy went to his typewriter and tapped out what's become one of the most familiar couplets in the English language. Right now on my local radio station, for example, the nearest body shop is making its pitch for winter tires by arguing that they're absolutely essential for when "the weather outside is frightful". And we all know what the guy's alluding to:

Oh, the weather outside is frightful

But the fire is so delightful

And since we've no place to go

Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!

Neither Sammy nor Jule was the kind of fellow whose vocabulary included "frightful". And I'm not even sure it's a word anyone would ever apply to meteorological conditions. But that's the point: It makes the very first rhyme unique to the song.

Why three "let it snows"? Why not two, or four? Because, as Sammy liked to say to me, "three is lyric." He was a great believer in the axiom that, if a thing is worth saying, it's worth saying again, and again:

Come Fly With Me

Let's fly

Let's fly away...

That's that big band sound he always heard in his head: If you were writing a long-lined ballad, you wouldn't instantly reprise the same phrase over and over because it would make the song seem very static. But, when Sammy wrote his lyrics, in his head he heard short rhythmic phrases pounded out by Woody Herman or Harry James.

So he typed out "Let It Snow!" thrice, and then he handed the quatrain to Jule. That's one way to measure how great a composer Styne is: You can't tell the lyric was written first. With the notable exception of Rodgers & Hammerstein, in the great American songbook the tunes were written first and then the lyric was fitted to them - which makes sense because, as a rule, lyricists are far more sensitive to the word or sound a particular note requires than composers are to the note or interval any particular word needs. But Styne had worked so long as a vocal coach that he had an amazing sense of singability, and, when Cahn gave him those lines, he knew exactly how to set them. "Let It Snow!" sings as natural as walking.

Look at that first couplet - the jaunty quavers for "oh-the-weath-er" and then the long notes for "fire" and "so". That's part of the reason why the fire is, indeed, so delightful – because those words sit on big notes full of warmth and yearning. Vaughn Monroe's Number One in 1946 would have been enough for Styne & Cahn. But it kept on and on, getting bigger and bigger. Here, five years after the song's composition, is Styne's onetime flatmate and Cahn's longtime pally, Frank Sinatra:

Nobody can say for sure what combination of notes and imagery - "I've brought some corn for popping" – separates a select couple of dozen seasonal standards from thousands of wannabes. And nobody would have predicted that Christmas songs would prove the most enduring songs, the last songs we all share. We don't have popular popular culture any more, so much as a bunch of competing unpopular popular cultures: There are folks who like rap and folks who like country, but not a lot who like both. And so, uniquely in this fragmented market, only the annual sleighlist crosses all boundaries. The Natalie Cole, Phil Spector, Dolly Parton, Motown, Bruce Springsteen, Andy Williams, 'N Sync, Diana Krall and Jessye Norman Christmas records all draw from the same limited repertoire, and thus millions of Americans who've never heard Jule Styne's great songs for Sinatra or Streisand nevertheless know "Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!" in versions by Garth Brooks, Marie Osmond, the Temptations, Sarah McLachlan, Lee Greenwood, Judy Collins, Brian Setzer, the Carpenters, Zane Musa, Smokey Robinson, Lorrie Morgan, the Studebakers, Olivia Newton-John, Chris Isaak, Diana Ross, Bugs Bunny, Jive Bunny, Epstein's Mother, the Dixieland Ramblers, the Gypsy Hombres, the Desert Wind Saxophone Quartet, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the Moscow Boys' Choir, and the Washington Gay Men's Chorus. And when you're through with that lot, check out Oscar Peterson's great romp through the tune, with Dave Samuels on vibes. That's cool in the non-frightful non-meteorological sense:

By contrast, let me close things out with one of the most recent recordings. From just a couple of months back, at the end of a year when ChiCom-19 ensured that we've all no place to go, here are the Goo Goo Dolls:

Hmm. A bit bland for my tastes, as rockers doing standards often are. So here's one more, from Rosemary Clooney. She asked Sammy to write her some extra lines for the out-chorus, and he gave it the usual forty seconds' thought. This couplet is very sweet:

Oh, the fire burned down to embers

But at our age who remembers?

Indeed.

~ The above contains excerpts from Mark Steyn's American Songbook, personally autographed copies of which are exclusively available from the SteynOnline bookstore. If you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter your special promotional code at checkout to receive even more savings on over forty books, CDs and other products.

If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Ted Nugent, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Paul Simon, Lulu, Tim Rice and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and we also have a special Gift Membership.

Our Netflix-style tile-format archives for Tales for Our Time and Steyn's Sunday Poems have proved so popular with listeners and viewers that we've done the same for our musical features merely to provide some mellifluous diversions in the Land of Lockdown. Just click here, and you'll find easy-to-access live performances by everyone from Herman's Hermits to Liza Minnelli; Mark's interviews with Chuck Berry, Leonard Bernstein and Bananarama (just to riffle through the Bs); and audio documentaries on P G Wodehouse's lyrics, John Barry's Bond themes, sunshine songs from the Sunshine State, and much more. We'll be adding to the archive in the months ahead, but, even as it is, we hope you'll find the new SteynOnline music home page a welcome respite from looting, lockdown and 'lections.

If you're a Mark Steyn Club member and you find the above column more frightful than delightful, let rip with what's on your mind in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page.