Our peerless film columnist Kathy Shaidle is away this week, and so I'm honored, after a stint as Tucker's guest-host, to step up and guest-host for Kathy, too. Miss Shaidle will return next weekend:

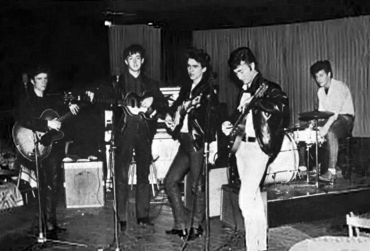

Forty years ago - December 8th 1980 - John Lennon was murdered as he returned home with Yoko Ono to the Dakota Building on Central Park West. He would be eighty years old now. I have written about him on and off over the years - "Imagine", his support for the IRA, my fondness for "Jealous Guy" and "Girl" and a couple of others - but it's a good general rule that the most interesting part of a celebrity's life is always the pre-celebrity years. So for our Saturday movie date this week I thought we'd screen Iain Softley's 1994 biopic Backbeat - the backstory to the beat, when the Fab Four were a fivesome trying to make it in Hamburg.

It helps, with any subject, to put a clock on it and a fence - to contain it within time and space, as last year's Judy Garland biopic did, boxing its protagonist into a short engagement in London at the Talk of the Town, at what she didn't yet know was the tail-end of her career and her life. For the Beatles, the formula is inverted: a short sojourn in Germany, pre-fame but not insignificant in terms of the group's development, and their brief encounter with Bert Kaempfert.

Nevertheless, my expectations of this picture were minimal, if only because, not for the first time, the tag-line sells it short:

He had to choose between his best friend, the woman he loved and the greatest rock'n'roll band in the world.

In other words, it's the old conflict between personal life and professional ambition which has motored every biotuner since the prototype Jolson Story in 1945. That movie ends in a nightclub - with Al Jolson, ostensibly having foresworn show biz for the little woman, being talked back on stage for a quick chorus of "April Showers" in the course of which his tearful wife realizes his first love will always be music and pushes her way through the cheering throng and into the divorce courts. Mass adoration versus human intimacy: it's no contest. "In the end, she's only a shag," observes John Lennon (Ian Hart) here. Backbeat winds up with its own eerie replication of the Jolson finale: "Twist And Shout" substitutes for "April Showers", but otherwise we've reached the same destination.

Mammy singers yield to crooners to big band swingers to rock'n'rollers, but the conventions of the musical biography remain unchanged. In The Glenn Miller Story, Glenn is obsessed with the need to play his music his way. So are Johann Strauss (The Great Waltz) and Buddy Holly: "I gotta play ma music ma way," he tells a man in a suit (representing hidebound conventions soon to be rendered obsolete) in the West End jukebox musical Buddy. In Backbeat, the Beatles in Hamburg find their musical identity with greater, er, speed. At the bar, a helpful stripper empties her bottle of intriguing tablets into the boys' palms, and suddenly the lads are on stage furiously ooh-ing and shaking their moptops. "Much better," decides John, still wide awake and staring at the bedroom ceiling hours later. "All the difference." This may be the most honest moment in any rock'n'roll movie. Most of the others go on about the "excitement" and "energy" of rock'n'roll; Backbeat just pulls it out of a bottle of pills.

At moments like this, Iain Softley's film is slyly subversive of its genre. For one thing, for a picture about 'the greatest rock'n'roll band in the world', it's amazingly offhand about the music. The Beatles chunter along through manky cover versions of Chuck Berry, early Motown, Johnny Mercer and "My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean" - and it all sounds sort of about how you'd expect a band in a third-rate club on the Reeperbahn to sound. It seems perverse to take the best-selling pop group in history and only show them as struggling teenagers, but, in fact, Softley has done what few superstar biographers succeed in doing: he's imposed some dramatic shape on the celebrity curriculum vitae. This is the Beatles' story as seen through one of its footnotes: the fifth Beatle, Stuart Sutcliffe. Stu prefers painting but he's gone along to Hamburg because John's his best mate. Paul McCartney — a bit of a fleshy creep here — doesn't like the way John's mate plays bass:

"What about Stu?" he asks John.

"What about Stu?" says John.

"He just stands there," says Paul.

John and Stu are pals; but Paul knows that love can't buy you money. When a record producer wanders into the club during Stu's dopey rendition of "Love Me Tender", Paul pushes him aside and cranks the band back into rock'n'roll mode. Soon the Mister Lennon/Mister Sutcliffe on-stage vaudevillian cross talk in which Stu and John indulge has been recast as Mister Lennon & Mister McCartney.

All the biotuner clichés are in here, but drolly inverted. Most of us know the Feeble Five dispensed with the fifth and became the Fab Four. But it comes as a surprise, in a film about the Beatles, that the passion and commitment and artistic obsession should be not about music but about Stu's painting. In traditional music films, the girl gets in the way; here, Astrid rekindles his need to paint. Cheekily, Softley has used the Beatles as a vehicle for a film about someone who chooses the personal and modest over the public and glamorous. Softley by name, softly by nature, he's attempting to draw something more complex than the usual glib lessons on the vicissitudes of showbiz.

Macca never cared for it. He complained that, as tends to happen in accounts of the Beatles, he wound up getting de-rockified by Backbeat. Paul's particularly irked that the film took "Long Tall Sally" away from him and gave it to John, even though "he never sang it in his life". But Lennon's murder set the bias of Beatleographers in stone, and in this telling as in others Paul gets short shrift.

It seems odd to cast as Sutcliffe an American who looks so obviously American (Stephen Dorff) and as his German girlfriend another American (Sheryl Lee from "Twin Peaks"). Neither is quite right, although the relationship is rather touching in the end. But it doesn't matter, because the film is as much about Lennon as Sutcliffe. It relies on Lennon's asides to defuse the sentimentality: "Breaks your fookin' 'eart," he remarks, as Stu and Astrid share a farewell embrace on a railway platform. And it's what Sutcliffe's friendship tells us about Lennon that keeps us interested. So, despite glamorous American casting and a skewed angle on a familiar story, Iain Softley can't entirely erase third years of rock legend: Stuart Sutcliffe ends up a supporting player even in his own story.

~The Mark Steyn Club is now in its fourth season. As we always say, membership in the Club isn't for everybody, but it does support all our content, on everything from civilizational collapse to our Saturday movie dates. What is The Mark Steyn Club? Well, it's a discussion group of lively people on the great questions of our time; it's also an audio Book of the Month Club, and a live music club, and a video poetry circle. More details here.

Oh, and if you're really sick of the lockdown and looting and 'lection, we have a fabulous cruise coming up next year, which is just the best way to bust out of this thing.