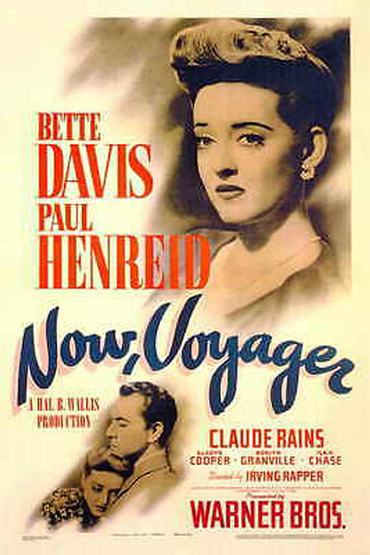

Having recently filed a few pretty "manly" movie columns, I figure it's semi-safe to test the patience of half my readership by writing about the Citizen Kane of "woman's pictures": Irving Rapper's Now, Voyager (1942) — or, as my husband wearily calls it, Not This Thing Again.

Here's one man who thinks it's great, though, if that helps takes the curse off it.

Now, Voyager is the story of Charlotte Vale (Bette Davis) — "of the Boston Vales" — who, when we meet her, is a frumpy, ingrown, unmarriageable mess. She's been rendered a sort of madwoman in the attic by one of the worst mothers in Hollywood history, a nasty crone who "was told that my recompense for having a late child was comfort in my old age, especially if it was a girl."

Charlotte's sister-in-law takes pity on her and, against mother's objections, brings a psychiatrist around, the no-nonsense Dr. Jaquith (Claude Rains).

He prescribes a season's stay in a sanitarium, then a South American cruise. When we next encounter Charlotte, she's undergone one of cinema's most startling makeovers.

(And it would have been even more startling had Davis gotten her way; it will surprise no one familiar with her work to learn that she wanted her "before" makeup and costuming to be even uglier.)

This "new" Charlotte, while still fragile, is nevertheless determined to take Jaquith's advice: mingle with people, say "yes" to life instead of "no." And one passenger, Jerry Durrance (Paul Henried), takes a great interest in her. He's the perfect man in every way — except he's (unhappily) married.

Charlotte and Jerry embark on a tentative romance, albeit a fairly chaste, courtly one. For the sake of his children, and his wife's own wobbly mental health, he will never break up his marriage, and Charlotte would never expect him to. For viewers, this bestows nobility upon what would otherwise be an adulterous affair. Thanks in part to the Hays Code, we're even granted plausible deniability as to whether or not the pair ever consummate their love, despite spending one night together.

"Even the censors of the time," writes the Movie Diva, "who habitually required extramarital affairs to be punished, couldn't bear to reprimand poor Charlotte."

The pair part after the cruise, but maintain a powerful if secret bond. Unless one factors in the rumored millennial phenomenon dubbed "Living Apart Alone," theirs resembles few real life relationships — and a stodgy realist will object that it is no "relationship" at all: that Charlotte and Gerry are treating each other more like secret pocket-sized talismans than fellow humans.

However, this is a movie, and their arrangement echoes a sublime, persistently powerful romantic archetype, one that embraces Heloise and Abelard and the Brownings, along with their platonic counterparts in popular culture: The X-Files' Mulder and Scully and Carol and Daryl on The Walking Dead. As with many long distance relationships, this archetype allows female viewers to fantasize about enjoying the status of "not being single anymore" without the disillusioning messiness of quotidian domesticity.

Still, Charlotte accepts a marriage proposal from one of the most eligible widowers in town. She explains her decision to Jerry, having run into him quite by accident. It's all so thrillingly classy.

Having been temporarily appeased by Charlotte's engagement to such a catch, mother is apoplectic when her daughter breaks it off. (He's no Jerry, after all...) Charlotte has responded to similar outbursts before magnanimity, but this time, she loses it.

Her mother's (super satisfying) death puts Charlotte in the same fortunate position as Catherine in The Heiress: given the female-unfriendly financial arrangements typical of the time, Charlotte is now free, having inherited the Vales' considerable wealth.

There's a lot more movie to go, but rather than ruin it, we need to talk about the floral dress Charlotte is wearing when she fatally confronts her mother in the above scene. Note how similar it is to the one she was wearing in her first appearance in the film, except it is more flattering. This is intentional, because while Now, Voyager seems to be A Tale of Two Charlottes, there are really four of them.

We've talked about Before Charlotte and After Charlotte, but there is also a Before Before Charlotte. In a flashback, we see her as a girl of twenty, also on a cruise, but this time with her mother. She's a young woman trying her nascent sexuality on for size, with a coltish combination of excitement and timidity — something not dramatized so daringly in too many films until the searing Smooth Talk in 1985.

By the time Charlotte's mother dies, she is also no longer the mysterious, be-caped glamor-puss on the cruise with Jerry, when her ticket, her finery, and even her name were borrowed from a sympathetic acquaintance in her social circle. Her understated yet attractive wardrobe in the final third of the film signals Charlotte's integration of her different personae into After After Charlotte: a poised, confident woman who finds purpose in life without a man — not even Jerry, although "he may come here" to visit "whenever he likes."

Jerry asks if this arrangement will make her happy, prompting the film's famous last line:

"Oh Jerry, don't let's ask for the moon. We have the stars."

Now as much as I adore this movie, that line smacks of a writer dying to get a long job over with and pour himself a well-earned drink or three. You're too busy crying to notice that it makes little sense — "What am I, chopped liver?" the moon might exclaim — but after the relentless emotional buildup, I'm pretty sure most viewers would weep at the end of Now, Voyager if Davis and Henreid burst into the Pledge of Allegiance.

But notice that the three final lines declare outright that this is not a happy ending. Charlotte's personality has matured and evolved to the point where "happiness" is not her goal. Despite its reputation for corniness and sentimental incontinence, melodrama primarily concerns itself with duty and sacrifice, not blissful romance. Any number of Davis' other melodramas conclude with her character's Zen-like resignation to life on life's terms. Genre master Douglas Sirk's most famous melodramas end on sombre notes, with one beloved nursing the injured other, or a death that sobers everybody up. Madame X (repeatedly) dies tragically, yet in peace, after sacrificing her life to spare her son's reputation; Stella Dallas can only watch her daughter's wedding through a window; after the couple kisses, she strides off in the rain, beaming.

Charlotte isn't happy, but she is content. A powerfully grown up message in a "mere" Hollywood film, and an old fashioned, even incomprehensible one if you think about the happy endings in most movies today: Wacky, splashy weddings are pretty much obligatory, you may have noticed. And of course, Sex Fixes Everything.

The much maligned woman's picture underwent rehabilitation during the 1970s and 80s, with scholars re-"reading" these films as proto-feminist texts. Not surprisingly, stills from Now, Voyager "were chosen to adorn the covers of the most influential books on melodrama, including Christine Gledhill's Home Is Where the Heart Is (1987), Jeanine Basinger's A Woman's View (1993) and Stanley Cavell's Contesting Tears (1996)."

More recently, the film has been upheld as a sensitive portrait of mental illness and its treatment. Angelica Jade Bastien has written extensively and perceptively about Now, Voyager, explaining to women of her generation what this now almost 80 year old movie means to her:

"Charlotte Vale and I are separated by race and class, culture and access. But in my late teens, shuffling between mental hospitals and new medications, Now, Voyager gave me what I couldn't find in reality (...) [A] spark of motivation and hope, the ability to imagine a future for myself when I was too poor to get therapy and too depressed to leave my bed. It was a small joy I held on to in dark times, a salve, a form of self-care. This is how a film can save your life."

~Let Kathy know what you think of this column by logging into SteynOnline and sharing below. Commenting privileges are among myriad perks reserved exclusively for members of The Mark Steyn Club, alongside exclusive invitations to Steyn events and access to the entire SteynOnline back catalog. Kick back with your fellow Club members in person aboard one of our annual cruises. We've rescheduled our Mediterranean voyage to next year, but it's sure to be a blast with Michele Bachmann, Tal Bachman, Conrad Black and Douglas Murray among Mark's special guests.