As the years go by, I am ever more certain that, of all the men and women who wrote the American songbook my desert-island composer is, no question, Jerome Kern. There are better songwriters (Irving Berlin, Cole Porter) and better musical dramatists (Richard Rodgers) but for popular music whose melodies and harmonies touch me as deeply as the great classical writers none beats Kern. I love the entirety of his catalogue - from his early London numbers in the Floradora style to the jazzy movie songs of the Thirties, from his trailblazing musical comedies with Guy Bolton and P G Wodehouse to his great Broadway epic Show Boat; "I Won't Dance" and "Smoke Gets in Your Eyes", "A Fine Romance" and "Ol' Man River", "Long Ago and Far Away" and "The Last Time I Saw Paris", "Yesterdays" and "They Didn't Believe Me", "All the Things You Are" and "The Folks Who Live on the Hill" and "Look for the Silver Lining" and "The Song Is You": The song is him.

Three-quarters of a century ago, he was working on a new Broadway show about Annie Oakley. On Monday November 5th 1945, after lunching at the Lambs Club with his old friend and collaborator Guy Bolton, Kern headed north on Park Avenue to do a little shopping: there was an antique breakfront at Ackerman's they thought he might be interested in. At the south-west corner of Park and 57th, he was waiting for the light to change when he suddenly fell to the sidewalk. A traffic cop, Joseph Cribben, saw what happened, and, after trying to revive him, dashed to a payphone and called for an ambulance. Still unconscious, Kern was taken to City Hospital on Welfare Island, and was placed in a ward for indigents and derelicts - because he had no identification about his person, save a card for something called Ascap, with which the staff were unfamiliar and which in any case gave only his member number and not his name.

Eventually, someone at the hospital looked up Ascap in the 'phone book - the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers - and told them they'd admitted an unknown patient with the following number. Ascap were horrified to discover one of their most eminent members was seriously ill in hospital, and scrambled to contact Kern's wife Eva and daughter Betty and Oscar Hammerstein (producer of the Annie Oakley show) and Dorothy Fields (librettist thereof), all of whom were off at lunch or meetings. By the time they got to the hospital ward, the indigents and derelicts had been made aware of the eminence in their midst, a man with whose songs and shows and films they were all familiar. Except for one brief moment, he never recovered consciousness. On November 11th at 1pm, Oscar Hammerstein sang into Jerry Kern's ear what he knew was the composer's particular favorite of the many songs they'd written together:

I've Told Ev'ry Little Star

Just how sweet I think you are

Why haven't I told you?

He thought for a second or two that there was a flicker of recognition. But ten minutes later all breathing had ceased and Jerome Kern was dead at the age of sixty.

So, to mark the seventy-fifth anniversary of his death, a Kern song. Many years ago - when a lot of the guys who wrote all the standards were still around - I started asking composers and lyricists to name their all-time favorite. Two Kern numbers were always in the running: The first was "All the Things You Are", with its exquisite enharmonic change of Schubertian beauty coming out of the release. But it has a lyric that for me trembles on the brink of over-ripe, and so I have a preference for the second. This one, on the basis of my unscientific surveys, came right at the top, tied with "It Had To Be You" - and I'll bet it would have won if a few writers hadn't grumbled to me, "Shame it doesn't have a verse."

It doesn't need one. It comes in as naturally as walking and says it all. I wonder if, back in 1936, Fred Astaire, who introduced more great songs to the world than any other performer, knew that he was premiering not just a pop hit, not just an enduring standard, but one of the handful of iconic songs that represent the absolute heights of the American Songbook. Probably not - because a) Ginger Rogers was washing her hair; and b) aside from the lather, he never got to twirl her cross the floor. Indeed, the number is all but unstaged:

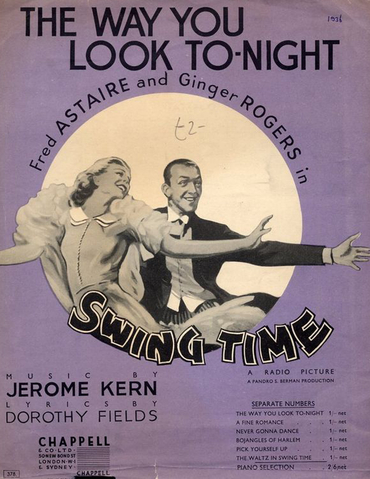

The film was Swing Time (1936) and Ginger's lather was actually whipped cream - just the way she looked that particular night, and Fred couldn't be more in love:

Lovely

Never never change

Keep that breathless charm

Won't you please arrange it?

'Cause I love you

Just The Way You Look Tonight.

Notice however the opening:

Someday

When I'm awf'lly low

When the world is cold

I will feel a glow just thinking of you

And The Way You Look Tonight...

For a song that makes so many people sigh with contentment, that's quite a bleak opening. As my old National Post colleague Robert Cushman wrote, it "jumps into sadness", which if anything understates the situation: "the world is cold." The transformative powers have their limits, and this song acknowledges them - there will be days when you're "awf'lly low" - but there are no consolations that will ever compare to the enduring "glow" of the way you look tonight. It acknowledges impermanence even as it celebrates forever.

Fred Astaire's original studio recording still sounds pretty good almost eight decades later: The arranger, conductor and pianist was Johnny Green, a man of many accomplishments and sufficiently serious about the later ones that he changed his billing to "John Green". Among other distinctions, he's the composer of "Body And Soul", one of the greatest popular compositions of the century. Yet, as he told me not long before he died, "I'm very proud of the recordings I made with Fred Astaire." They made Astaire not just a Broadway and Hollywood dance man but a force on records, too:

Fred introduced the song serenading Ginger Rogers in the 1936 picture Swing Time, the danciest of Astaire and Rogers' RKO musicals and with a wonderful score by Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields. By the mid-1930s, Kern, composer of Show Boat and much else, was the dean of American songwriters. Richard Rodgers used to say that he had one foot in the old world and one in the new. That's to say, Kern wrote gorgeous ballads, and in his days with P G Wodehouse fun comedy numbers, but he had no great interest in swing, and his occasional forays into more vernacular forms can sound faintly condescending: "Can't Help Lovin' That Man Of Mine" bears the marking "Tempo di blues". But, teamed with the younger Dorothy Fields, Kern turned in one of his best ever scores. The plot of Swing Time is genial hokum: Astaire plays a chap who turns up so late for his own wedding that his father-in-law-to-be tells him to push off and not come back until he's earned 25 grand. Looking for an easy way to solve his financial woes, Fred runs into a dance instructress, played by guess who. Complications ensue, but so does song and dance. Astaire and Rogers always got the best songwriters – Irving Berlin, the Gershwins – and Kern and Fields more than held their own. In fact, you could make the case that it's the best of all Fred-and-Ginger scores, notwithstanding the objections of the New York Times reviewer:

Right now we could not even whistle a bar of 'A Fine Romance', and that's about the catchiest and brightest melody in the show. The others... are merely adequate or worse. Neither good Kern or good swing.

Among the "merely adequate or worse" numbers was not only "The Way You Look Tonight" but "Pick Yourself Up". "Dorothy wrote so many good songs with Jerry," James Hammerstein, Oscar's son, said to me. "Some of the funnier ones - 'A Fine Romance', 'Bojangles Of Harlem', that whole score is marvelous. 'Pick Yourself Up' is one of his better 'up' tunes." Of the seven songs in the film, Astaire made pop records of five of them, and all were big sellers.

Most of Kern's best "up" tunes were written with Dorothy. But it didn't come easy to him. Astaire's rehearsal pianist, Hal Borne, thought Kern was squaresville and his syncopations corny. Fred himself was depressed by the score. As he told Miss Fields, "Can't this guy write anything hot?" Dorothy sympathized, and Astaire came round to the house and tapped his way up and down the living room and up and down the stairs and eventually Kern got with the program and wrote "Old Bojangles Of Harlem". Eight decades on, Swing Time's score contains some of the composer's hottest numbers in every sense – his most performed compositions, and songs with a sensibility quite different from the broad arioso ballads and charm songs he wrote with Oscar Hammerstein, Otto Harbach and others. Dorothy Fields brought out a different quality in his work. They called "A Fine Romance" "a sarcastic love song", and it is. Lehman Engel, the master analyst of Broadway, used to say that Dorothy Fields' lyrics "dance". Yes, they do. Some of them dance literally – that's to say, they're songs about and for dancing, in shows and films. But others dance right out of their context and become songs for everyone.

Few songs do it on the scale "The Way You Look Tonight" did - the least "hot" number (to use Astaire's criterion) in Swing Time's dancing score. Aware that the suits were deliberating on whether he was past it, Kern (in his early fifties) decided that the most effective way to return fire was in the music: "The Way You Look Tonight" is entirely devoid of swing; every note of the melody is right on the nose, right on the beat: Some... day... - whole note, whole note; When the world is... I will feel a... Just thinking of... crotchet, crotchet, crotchet, crotchet... crotchet, crotchet, crotchet, crotchet... crotchet, crotchet, crotchet, crotchet... "To hell with you swingers bitching about my corny syncopation," Kern seems to be saying. "I ain't gonna syncopate nuthin'. This one's for me!" So it flows, and never stops flowing.

"The first time Jerry played that melody for me, I went out and started to cry," Dorothy Fields recalled. "The release absolutely killed me. I couldn't stop, it was so beautiful." "The song flows with elegance and grace," observed Alec Wilder. "It has none of the spastic, interrupted quality to be found in some ballads, but might be the opening statement of the slow movement for a cello concerto."

As the author William Zinsser pointed out, "The first eight bars of almost any Kern melody - 'The Way You Look Tonight', 'All the Things You Are', 'Long Ago and Far Away' - move in a continuous line, not pausing to develop what has gone before." Most popular composers work in shorter bursts, repeating two-bar melodic and rhythmic ideas to aid memorability: To take that other über-standard: "It had to be you"; repeat a tone up: "It had to be you"; Take the phrase up another notch: "I wandered around"; And reprise it instantly: "And finally found..." Nobody's expecting Isham Jones to be Jerome Kern, but even George Gershwin does a lot of this: "Embrace me, my sweet embraceable you"; take the phrase up: "Embrace me, you irreplaceable you..." But a Kern phrase starts and flows to the end like one sustained continuous thought. It's an AABA song, but unhurriedly so, with 16-bar sections. Dorothy Fields got the idea. She wrote her own flowing line, a 26-word sentence, with one very unobtrusive rhyme:

Someday

When I'm awf'lly low

When the world is cold

I will feel a glow just thinking of you

And The Way You Look Tonight...

"Glow" - that half-buried rhyme - is the trick of the song. Kern wrote a very tender melody, and Miss Fields matches it in all its sweet warmth, I love the unobtrusive but perfect words she puts on the three pick-up notes with which the composer starts the second section:

Oh, but you're

Lovely

With your smile so warm

And your cheek so soft

There is nothing for me but to love you

Just The Way You Look Tonight...

Another disguised rhyme - "warm" is paired with "for m/e" - and "love you" completes "of you" in the previous section. The middle section - the release - keeps the song's flowing quality. Most composers will opt for contrast - a legato middle following a choppy, staccato main theme - but Kern's "release" seems just that: a natural development of the principal strain, moving in the sheet from E flat to G flat and then noodling back in one of those quintessentially Kern transitions:

With each word your tenderness grows

Tearing my fear apart

And that laugh that wrinkles your nose

Touches my foolish heart...

That's beautifully poised. The lyric trembles on the brink of grandiosity, but then settles for a rueful, human, goofy sentiment - the potentially overblown fear-tearing balanced by the nose-wrinkling, an image of great intensity and intimacy and true tenderness. Lesser writers were wont to give serious love songs to the serious love interest and funny songs to the comedy couple and ne'er the twain shall meet. But most of us are serious and funny, romantic and hokey, sensuous and foolish all at the same time – and few songs walk that tightrope as adroitly as this one.

After its debut in Swing Time (1936) it went on to win the Oscar for Best Song – a tough year, too: the other nominees included a brace of numbers Sinatra would keep in his act right to the end, "Pennies From Heaven" and "I've Got You Under My Skin". Yet "The Way You Look Tonight" is indisputably the best of the first four Best Song Oscars – "The Continental" (1934), "Lullaby Of Broadway" (1935) and the ridiculous plastic-fronded pseudo-Hawaiian "Sweet Leilani" (1937) – and way better than any winner of the last quarter-century. In fact, if it was eligible, it would probably still be winning Oscars today. Six decades after it was written, it was still making a pretty good screen song – see My Best Friend's Wedding or Hannah And Her Sisters or Father Of The Bride or Ross proposing to Rachel on "Friends", or the melancholic Ken Branagh pic Peter's Friends, where it's sung by a full country-house party with Hugh Laurie at the piano, and it binds the fractured friends as nothing else does:

It wasn't always that big. For a while, recordings of it weren't that numerous, as if Astaire and the film had too strong a proprietorial grip on it. At the time, Billie Holiday and Guy Lombardo did it - separately, I hasten to add - and then it sort of faded away, as things did, until a young Peggy Lee and Benny Goodman - not separately, I'm happy to say - had a modest hit with it in 1942. The rhythm section dials back the volume, but Mel Powell's celeste is terrific:

The following year Frank Sinatra was hosting his own radio show on CBS, "Songs By Sinatra", and decided to do "The Way You Look Tonight". In 1943, the American Federation of Musicians was on strike and boycotting the recording studios. On the other hand, there was a war on. So, in late October, AFM honcho James Petrillo agreed to allow union musicians to be heard on "V-Discs" - as in V for Victory, special records for the troops that Petrillo okayed on the condition that they were not available for sale in the United States. And so it was that, a couple of weeks after the deal had been struck, the dress rehearsal for "Songs By Sinatra" became a simultaneous recording session, and "The Way You Look Tonight" wound up getting pressed as V-Disc 1168 and shipped to America's fighting men overseas.

Frank dispenses with an intro and starts cold on "Someday", and what follows is lovely:

The string arrangement by Axel Stordahl is perhaps a little old-fashioned (although I'll bet Kern loved it), but young Frankie's close-miked vocal is very tender and expressive. If you were listening out in the Pacific or on some hillside in Italy, the world was certainly cold and you were awf'lly low. In such circumstances, being reminded of the way she looked that night may or may not be helpful. But, in a sense, the scenario foreseen by Fred Astaire seven years earlier had come to pass. Sinatra sings just one chorus, and he lets the Bobby Tucker Singers handle the little "hums" with which Kern punctuates the sections of the song. Dorothy Fields was shrewd enough not only to know when not to rhyme but also when to dispense with words entirely – as in that accompanimental figure which eventually turns up at the end as a four-bar tag to wrap up the whole song. No words, just a perfect, contented hum – "Mmm, mmm" – or, as Kern more pretentiously put it in the vocal direction on the sheet music, "Bouche fermée". Nothing wrong with the Bobby Tucker Singers, but I think they intrude on the intimacy, and, given the romantic tingle Sinatra brings to the main vocal, it's a shame he didn't get to handle those hums.

A lot of singers love that little hum, but I've only ever heard one version make it work up-tempo – Sinatra's swinging "Way You Look" to a driving Nelson Riddle arrangement, with a closing hum of pure contentment. (He waited awhile for that hum: The strings get to play it in subtly different registers throughout the track until he gets his turn.) It was 1964, two decades after his first take on the song, and a few years past the peak of the Sinatra/Riddle relationship and their killer concept albums. Songs For Swingin' Lovers was an album of love songs that swing, In The Wee Small Hours"is a set of songs for spilling your guts out, but the concept for Frank Sinatra Sings Days Of Wine And Roses, Moon River And Other Academy Award Winners was a bunch of songs with nothing in common other than an Oscar on the mantlepiece. The whole is somewhat unsatisfactory, but some of the parts are excellent, and none better than Kern and Fields' much recorded standard. "Once while I was driving," said the trumpeter Zeke Zarchy, "I heard an old record by Frank and Nelson, and I had to get out of the car and call the radio station. It was 'The Way You Look Tonight", the greatest thing I have ever heard! I defy any instrumentalist to swing like he does with his voice on that record":

If his 1943 record with Axel Stordahl is shy and tender and loving, the 1964 Riddle arrangement is confident and sexual. And, if Kern's melody was his revenge on the studio hipsters demanding swing, Sinatra's arrangement was a kind of unconscious revenge on the composer: The non-swinging tune transformed into nothing but hard swing. Thousands of singers sing "The Way You Look Tonight" without it ever becoming their song - the way "Mona Lisa" is Nat Cole's or "Fever" is Peggy Lee's. But over time Sinatra's counter-intuitive "Way You Look" became the most widely heard. In the Eighties, Michelob used it to sell beer in one perfect package - the glamour of Manhattan nights, the style of Sinatra:

Is that Frank Jr on the voiceover? "One taste will tell you why" certainly sounds like him.

Sinatra never sang "The Way You Look Tonight" in concert - except in this commercial, where he lip-synchs along with his two-decade-old recording, after pretending to rehearse it. It's a very cool time capsule of the day before yesterday. As Ed Driscoll writes:

The telephoto lenses, the night cinematography, the big hair on the women, the suit and T-shirt, Miami Vice-style on the guy at the end, the Jennifer Beals-lookalike next to him — that's the 1980s overculture right there.

And then the final image: Sinatra and the twin towers of the World Trade Center. Lovely, never never change...

It was a hit commercial, and it made that 1964 Riddle chart a key recording in the song's transition from fondly recalled Astaire ballad to the first choice for movie wedding scenes and rockers' standards albums and sitcom special-guest appearances. And, from the Nineties onward, the recordings never stopped: Harry Connick Jr, Steve Tyrell, Maroon 5... The Irish boy band Westlife put two versions of the song on the Japanese release of their Rat Pack tribute, Allow Us To Be Frank. But I don't think either is a threat to Sinatra and Riddle. Almost alone among her contemporaries, Gloria Estefan, for whom I have a great respect in these matters, found an arrangement that works for her:

Sometime in the Nineties, that 1964 recording with Nelson Riddle wound up in Rutledge Hill Press' series of "Note Books": Frank's CD single plus a slim volume with Dorothy Fields' lyrics illustrated, and a few lessons in love from Sinatra himself:

It took me a long, long time to learn these things and I don't want these lessons to die with me.

I believe in giving a woman a lot of time to make up her mind about the guy she wants to spend the rest of her life with.

A man just doesn't like being crowded with female claustrophobia...

Make her feel appreciated. Make her feel beautiful. If you practice long enough, you will know when you get it right...

I notice that good manners – like standing up when a a woman enters the room, helping a woman on with her coat, letting her enter an elevator first, taking her arm to cross the street – are sometimes considered unnecessary or a throwback. These are habits I could never break, nor would I want to.

Sad that letting a woman enter the elevator first is now sufficiently rare to be viable as a "tip".

And finally:

Most of all, I believe a simple 'I love you' means more than money. Tell her, 'I will feel a glow just thinking of you'...'your smile so warm and your cheeks so soft,' 'that laugh that wrinkles your nose,' your 'breathless charm,' '...never, ever change.' 'I love you...just the way you look tonight.'

Indeed. The peerless singer of the 20th century, the greatest female lyricist, the dean of American popular composers, and a song that will live forever:

Lovely

Never never change...

~You can read more about Dorothy Fields in Mark Steyn's American Songbook. Personally autographed copies are exclusively available from the Steyn Store. If Astaire, Sinatra and the rest have the English lyric pretty well covered, Mark has always liked the French text of the song, and a few years ago he went into the studio and recorded it. You can download it here, or get it on his Goldfinger CD.

If you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter your promotional code at checkout for special member savings on both that CD and book and dozens more Steyn Store products.

If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Ted Nugent, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Paul Simon, Lulu, Tim Rice and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and we also have a special Gift Membership.

Our Netflix-style tile-format archives for Tales for Our Time and Steyn's Sunday Poems have proved so popular with listeners and viewers that we've done the same for our musical features merely to provide some mellifluous diversions in the Land of Lockdown. Just click here, and you'll find easy-to-access live performances by everyone from Herman's Hermits to Liza Minnelli; Mark's interviews with Chuck Berry, Leonard Bernstein and Bananarama (just to riffle through the Bs); and audio documentaries on P G Wodehouse's lyrics, John Barry's Bond themes, sunshine songs from the Sunshine State, and much more. We'll be adding to the archive in the months ahead, but, even as it is, we hope you'll find the new SteynOnline music home page a welcome respite from looting, lockdown and 'lections.

If you're a Mark Steyn Club member and the above column is making you awf'lly low, feel free to let rip in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page.