In the days immediately following September 11, as the story of Flight 93 fitfully emerged, I couldn't help thinking — being me and all — "Wow, what a great movie that will make some day."

When that movie did come out in 2006, I bought the DVD out of duty, but it's still wrapped in cellophane. That same year, I tried watching A&E's dramatization of the mutiny on that doomed aircraft, but began hyperventilating a few minutes in and had to bail.

And now, almost 20 years after that awful day, images of 9/11 still anger and depress me, making each anniversary a challenge to get through.

But at least once a year, I re-watch a film made fifty years earlier, about an alien attack on a motley band of Americans trapped in a confined, relentlessly isolated space, bereft of outside assistance — except for the clueless instructions and protocols they receive from far-off authorities — who must improvise a counterattack with whatever tools they can scrounge, and all the moxie they can muster.

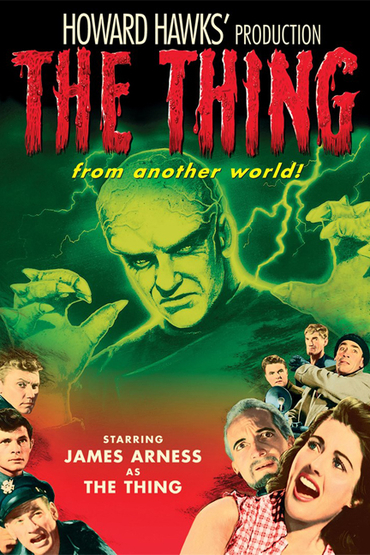

The Thing from Another World (1951) is set at the North Pole, where a circular aircraft, clearly not of this earth, has crashed. An Air Force crew led by Captain Hendry is dispatched to investigate, with a civilian reporter in tow, then meet up with a scientific expedition already stationed in the area.

An alien's body entombed in ice is recovered at the crash site and hauled to the station, where it thaws out and goes on a rampage. This prompts heated arguments about whether the alien should be captured alive for study, or killed at the first opportunity.

Once radio contact is re-established, Air Force brass agrees with the expedition's head scientist, the profoundly annoying Nobel Prize winner Dr. Carrington:

Hendry and his men are ordered to put the interests of science ahead of their own safety and survival — this "thing" must not be destroyed. Instead, we must try to "understand" it.

Note that in the clip above, Carrington views the violent alien as the "real" victim: Why, it's only angry because it was "attacked by dogs" and "shot at" — when in fact the "thing" attacked the dogs to suck their blood, and was fired upon after lunging at a crewman. Shades of "America asked for it..."

The conflict between cerebral science and what (for lack of a more felicitous phrase) I'll call earthy common sense became a recurring theme in 1950s science fiction films thereafter, but was never better captured than in this bouquet of dialogue in The Thing From Another World.

Carrington: "But you fools, don't you understand? Science is more important than life itself! Without science, we never would have split the atom!"

Soldier: "Yeah, that cheered everybody up."

It's a line you'd expect to hear a quarter century later in M*A*S*H, and even then, it would have been uttered by a jaded, jokey surgeon, not an enlisted man. Didn't the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki hasten the end of the Second World War and spare the lives of numberless Allied servicemen who'd have perished in a drawn out land invasion of Japan? Yes, but no sane soldier revels in the gruesome deaths of enemy civilians, no matter how "justified." That's one of many attributes that distinguishes us from our 9/11 enemies.

Representing both science and, more broadly, academia, Dr. Carrington insists that the alien is an underdog-victim who's aberrant behaviour must be accommodated and even celebrated: he repeatedly calls this "vegetable" creature superior to mere humans.

But this is a revealing projection on Carrington's part. As one writer notes:

"[Carrington] is sympathetic to [the alien] because he sees it as an extension of himself — intellect devoid of emotion, feeling, or pain, the perfect scientist (although the viewer sees it as a violent, rampaging monster that demonstrates little intelligence, only strong survival instincts)."

The narcissistic, bubble-dwelling intellectual who prioritizes rarefied theory above what's happening before his very eyes, let alone the preservation of individual lives, is a figure we know all too well from real life, and justifiably despise.

These same viewers of The Thing... may look upon one of its characters with longing, however. Today we assume, with good reason, that journalists are raving leftist desk jockeys. Yet the film's reporter character, Scotty, justifies his presence by telling the Air Force crew he's "one of them" in his own way; they needn't worry about him panicking during the final assault on the alien, because he too "was at El Alamein, and Bougainville, and Okinawa."

The Thing From Another World has often been called Howard Hawk's "answer film" to the ultra-liberal The Day the Earth Stood Still. They are tied for the distinction of being the first movies to depict an alien setting foot on our planet, having both come out the same year, but for that very reason, the "answer film" theory doesn't hold up: Both movies would have been in production simultaneously.

(And whether or not Hawks was the "real" director of The Thing... is a decades-long dispute I'll steer clear of here, except to say he probably was.)

But even if The Thing... wasn't made intentionally to undermine The Day the Earth Stood Still, it still decidedly does so.

The latter film valorizes science, academia and the United Nations, and in the end, the Christ-figure alien tells the poor, stupid humans they clearly aren't ready to hear his message of peace and love (and, er, submit-or-die authoritarianism), all because dumb soldiers keep firing at his giant uninvited UFO and his huge super-powerful robot. Idiots!

Frankly, I've never seen much difference between Klaatu's widely-lauded Sermon on the Spaceship, Chaplin's toxic speech in The Great Dictator, and this bit from Plan 9 From Outer Space.

Whereas in The Thing..., human ingenuity, courage and camaraderie are prized above abstractions. The alien isn't hated for being alien, but for being demonically violent; it cannot be reasoned with, so with lives at stake, it must be destroyed. However flawed, humans are masters of their own fates. We don't need saving by interplanetary bodhisattvas, thank you.

In one of the most thoughtful essays on The Thing From Another World, Elizabeth A. Kingsley writes:

"The uneasy world politics of the early fifties may have inspired the film, but Howard Hawks was careful to provide answers to the questions that his film raised, and to reassure those watching that America's security was safe in the hands of brave, clever, resourceful men and women, who could be relied upon to rise to any occasion, and deal with any crisis. Despite its flying saucer from somewhere else, its rampaging monster, and its untrustworthy scientist, it is likely that the audiences of 1951 found The Thing to be a strangely comforting experience."

The "uneasy world politics" refers, of course, to the Cold War. Some might see The Thing's... arctic setting as one big metaphoric pun, and liberal writers (the type who still insist on putting "the Red Scare" in quotation marks long after the release of the Venona Papers) will inform you that the film "has an unmistakable anti-communist bent. (Carrington is practically dressed like a Cossack as he acts as a human shield between the U.S. troops and the alien, pleading to the former that the Thing's wisdom is simply beyond American comprehension just before it beats the crap out of him)."

To which readers of this site will respond, "So what?" and be all the more eager to watch it.

The Thing From Another World is also routinely, and lazily, categorized as a "B-movie," and while it was made for second tier studio RKO, it had an "A" budget and it shows. It clocks in at just under 90 action-packed minutes, and in between the fights and frights, witty, rapid-fire, overlapping dialogue (a Hawks trademark; his regular collaborator Ben Hecht performed uncredited rewrites) carries the film along.

Scotty's final lines may be less prescient than they were right after September 11, but the last scene never fails to give me goosebumps. The Thing From Another World may not retain its power to scare audiences, but its ability to inspire them remains.

SCOTTY: Anchorage, from Polar Expedition. Can you hear me? Over.

RADIO CONTROL: Anchorage, reception clear. Stand by.

SOLDIER: Press the button and speak, Scotty.

SCOTTY: Tell General Fogarty we've sent for Capt. Hendry. He'll be here in minutes.

RADIO CONTROL: Roger. Over.

SCOTTY: Are there any newsmen there? Over.

RADIO CONTROL: The place is full of them. Over.

SCOTTY: All right. Here's your story: North Pole, November 3rd. Ned Scott reporting. One of the world's greatest battles was fought and won by the human race. A handful of American soldiers and civilians met the first invasion from another planet. A man by the name of Noah once saved our world with an ark of wood. Here, a few men performed a similar service with an arc of electricity. A flying saucer which landed here, and its pilot, have been destroyed. But not without casualties among our own meager forces. I'd like to bring to the microphone the men responsible for our success. But Capt. Hendry is attending to demands over and above the call of duty. [Hendry's in the background, snuggling with his girlfriend.] Dr. Carrington, leader of the scientific expedition, is recovering from wounds from the battle. [True, but not really. In spite of everything, Scotty (and Hawks) want to help Carrington save face.]

SOLDIER: (sotto voice) Good for you.

SCOTTY: And now, before giving you the details of the battle, I bring you a warning. Every one of you listening to my voice... tell the world. Tell this to everybody wherever they are: Watch the skies everywhere. Keep looking. Keep watching the skies....

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think of this column by logging into SteynOnline and sharing below. Membership in the Mark Steyn Club has many perks, from commenting privileges, to access to the entire SteynOnline back catalog, to exclusive invitations to Steyn events. Take out a membership for yourself or a loved one here. Kick back with your fellow Club members in person aboard one of our annual cruises. We've rescheduled our Mediterranean voyage to next year, but it's sure to be a blast with Douglas Murray, John O'Sullivan and Tal Bachman among Mark's special guests.