Herk Harvey was driving from Los Angeles back home to Lawrence, Kansas when he saw it: a crumbling yet stubbornly still-there pavilion near the shore of Utah's Great Salt Lake, surrounded by absolutely nothing — a worse-for-wear Xanadu plunked into a vacant arid landscape.

This was the Saltair Resort, constructed by Mormons as their very own "See, we can have fun, too!" amusement park in 1893, complete with one of the largest and most popular ballrooms in the U.S. (Even Glenn Miller played there.) In aptly Old Testament fashion, any fun was short-lived: The lake retreated, and the fanciful Moorish pavilion caught fire four times. Fate, or God, enjoyed one last rebuking laugh on the carnival grounds, then silence fell like a shroud.

When Harvey arrived back at his job as an industrial and educational film director at Lawrence's Centron Corporation, he asked staff writer John Clifford if he felt like penning a feature film screenplay.

Harvey's only stipulation was that the last scene "had to be a whole bunch of ghouls dancing in that ballroom."

"I said, 'Sounds good to me,'" Clifford dryly recalled decades later.

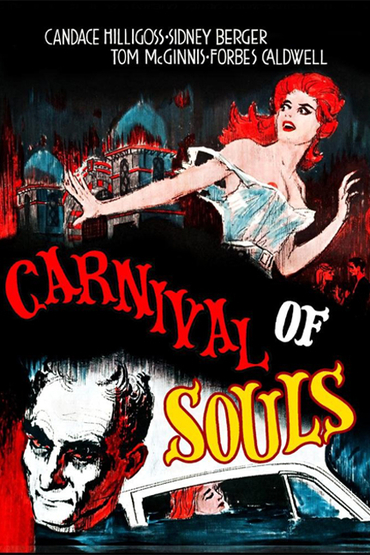

The result was Carnival of Souls, shot without permits by Harvey and a five-man Centron crew over three weeks' banked vacation time. The budget was $30,000.

Carnival of Souls was released in 1962. The distributor, Herz-Lion, chopped out a few minutes to squeeze it onto a drive-in double bill, and resented Harvey's refusal to go back and shoot even one nude scene. (Unusually for its time, and ours, the film has no love story.)

This animosity didn't matter for long: The distributor went bankrupt soon after. Their checks to Harvey bounced. He never made another film.

Ironically, Herz-Lion's final insult ensured the film's fame: they illegally sold copies to television stations that had local "horror hosts" eager for fresh content every Friday or Saturday at midnight.

That was how most viewers discovered Carnival of Souls. It became more of a rumor than a movie, like a "lost" Twilight Zone episode some began to doubt even existed despite having seen it for themselves, such was its hallucinatory strangeness.

First-time viewers of Carnival of Souls can be forgiven for thinking they've tuned in late, or that an establishing scene was recklessly cut by a time-stingy program director, but no:

In a credit-free sequence echoing the cautionary safety shorts Harvey shot for Centron, we come smack in on a "chicken run" challenge between two speeding cars — one of them, unexpectedly, driven by and filled with females.

One of those passengers, Mary Henry (Candace Hilligoss), is the only one not enjoying this reckless game. Her fears are fulfilled when the car she's in careens off a bridge and into the river.

All three girls inside are presumed drowned, until Mary alone drags herself out of the water just after searchers decide to give up. She is muddy and disoriented, but otherwise miraculously unharmed.

Days later, Mary is at an organ factory, testing out the same model she'll be playing at her new job with an out of town church. So soon after the accident, she seems perfectly normal – or does she?

The factory owner:

"Well, Mary, you'll make a fine organist for that church. Be very satisfying to you, I think."

"It's just a job to me."

"Well, that's not quite the attitude for going into church work..."

"I'm not taking the vows. I'm only going to play the organ."

"Mary, it takes more than intellect to be a musician. Put your soul into it a little, okay?"

Then: "Feel free to stop by again if you're ever back this way," the owner calls as she walks out the door.

"Thank you, but —" Mary's voice is jarringly firm — "I'm never coming back."

I'm pretty sure it's the last time Mary says "thank you" during Carnival of Souls. She's not exactly rude, but she's not polite, either. A pretty young blonde, Mary is uninterested in the attentions of men, and makes no attempt to ingratiate herself with women, either. In all this, she resembles the typical self-contained Hitchcock blonde, not the docile, domesticated females Betty Friedan would claim, the following year, were silently suffering, in their millions, across the nation.

Like Marion Crane in Psycho two years earlier, Mary drives through the dark toward her destination, but is sidetracked by two things: Not a patrol cop and the Bates Motel, though, but the pasty, grinning face of The Man (director Harvey) in her passenger window, and then the ruins of Saltair. Both haunt her.

Mary balks when her new boss, the reverend, suggests holding a reception to welcome her to the congregation.

"Couldn't we just skip that?"

The minister is thrown off. "I don't know what some of the ladies will say..."

"If they say I'm a fine organist, that should be enough, shouldn't it?"

Mary tries to settle into her new home, a boarding house with one other tenant, the slimy, sweaty Mr. Linden, whom Roger Ebert memorably described as "a definitive study of a nerd in lust."

But The Man appears again, his chalky face staring back at her through her window. The next day, the minister agrees to drive her to Saltair. She's determined to explore the grounds, not just look through the fencing, but he tells her that's against the law. The place is condemned. They leave.

Incrementally, Mary's grip on reality slips away (although whether or not she had one to begin with is ambiguous.)

She's fired from her organist job after playing "sacrilegious" music in a trance, goes on a disastrous date with the lecherous Linden, and runs randomly through the town, trying to escape The Man while being drawn back to Saltair, where The Man and his minions await, beckoning her to join their macabre dance. A chase ensues. Mary collapses onto the sand.

We flash back to the film's opening sequence:

The doomed car is dredged from the depths.

With a drowned Mary inside it.

With that "she was dead all along" twist, Carnival of Souls echoes Ambrose Bierce's widely anthologized short story "An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge," which was then having a "moment" long after its publication in 1890: An adaptation aired on Alfred Hitchcock Presents in 1959, and a 1962 French version was acclaimed at Cannes and the Oscars.

Why? Greater minds than my own have tried to puzzle out the phenomenon of "twin" (or even "quintuple") movies and other uncannily alike cultural artifacts that materialize simultaneously, as if responding to some inarticulable hunger within the collective unconscious.

Simply saying, "There was something in the (salt) air" feels inadequate, but I honestly have nothing helpful to add. What is undisputed is that Carnival of Souls, obscure as it was, became an admitted influence on directors George Romero, Brian De Palma, M. Night Shyamalan and David Lynch.

That the film's protagonist is a woman ("hounded" by male figures recalling unhelpful versions of Dorothy's companions in Oz) has inevitably encouraged feminist interpretations of Carnival of Souls. This is not entirely wrongheaded: Women do experience the world differently. A sequence in which a desperate Mary is rendered invisible and unheard — and when heard, dismissed — by those around her certainly resonates.

(As Eve Tushnet and others have noted about the horror genre, "the [characters] who know the truth are the ones least likely to be believed," and those characters are frequently female — the "final girl" archetype first proposed by Carol Clover.)

"Mary is surrounded all the way through the film by men who are trying to explain things to her, or trying to work out what she's playing at," Anne Billson says in a video essay that accompanies Carnival of Souls' gorgeous Criterion 4D restoration (which is the only way to watch it.) "You could interpret it as a story of her trying to assert her own identity in the face of what society expects her to be."

And female viewers may be less baffled than they'd like to admit when Mary abruptly goes out with the oft-rebuffed Linden after all: In her lonely torments, Mary would rather be with someone, if just for one night, than with no one at all.

The reverend and organ factory owner chide Mary for not being "spiritual" enough, while Linden predictably accuses her of being frigid. So far, so typically patriarchal, say feminist critics, but that's not entirely fair. Mary is strange, and these conventional fellows naturally don't know what to make of her. Mary doesn't know what to make of herself.

Frankly, one could just as easily theorize that Mary is autistic. Asperger's presents a touch differently in women, although some symptom lists sound no more precise than a tabloid horoscope. That said, Mary is hermetically sealed to an atypical degree. When one factors in her vocation, organ playing — demanding as it does an amount of rocking and foot-tapping — the analogy snaps into focus.

I just made all that up though. Harvey and company settled upon Mary's profession because there was a Gothicly photogenic (and available) organ factory close by. The eerie diegetic music that instrument would provide was a happy bonus that enhances the film considerably.

But still, for these reasons, Carnival of Souls doesn't fit easily into the "Dead All Along (Or Should Be)" genre — think The Sixth Sense and Final Destination — because it's unclear whether or not Mary is attempting to outrun death, or life.

Having spent the entire film insisting she doesn't want any part of society, Mary gets her wish. It isn't God who sends us to hell. We send ourselves.

~Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think of this column by logging into SteynOnline and sharing below. Membership in the Mark Steyn Club has many perks, from commenting privileges, to access to the entire SteynOnline back catalog, to exclusive invitations to Steyn events. Take out a membership for yourself or a loved one here. Kick back with your fellow Club members in person aboard one of our annual cruises. We've rescheduled our Mediterranean voyage to next year, but it's sure to be a blast with Douglas Murray, John O'Sullivan and Tal Bachman among Mark's special guests.