Watching American cities burn across the map all summer long is a little dispiriting for those of us foreigners whose first acquaintance with these burgs was through American songs. I have been to St Louis a handful of times, but, if you sneak up on me unawares and yell the name at me, I'm more likely to eschew my limited personal experience and burst into a few bars of "Meet Me in St Louis" or "The Saint Louis Blues" - notwithstanding that the former renders the town exclusively as "St Louiee" and the latter does likewise in all but a few recordings.

"The Saint Louis Blues" was written in 1914, but its first smash hit recording is currently celebrating its hundredth birthday. Insofar as these things can be reliably measured, in October 1920 this was America's bestselling record:

That's Marion Harris, a great star of the 1920s and all but forgotten today. Miss Harris died in 1944, when she fell asleep while smoking in bed and burned to death. But she was the most important white female to sing jazz and blues in the early years of those genres. She started her recording career at Victor Records, singing "Everybody's Crazy 'Bout the Doggone Blues, But I'm Happy", "When I Hear That Jazz Band Play", "A Good Man Is Hard to Find" and "I Ain't Got Nobody". "She sang blues so well," said W C Handy, "that people hearing her records sometimes thought that the singer was colored." But Victor Records felt her performance of Handy's "Saint Louis Blues" was going a little too far and refused to release it. And so Miss Harris walked out of her record company and over to Columbia, who made a small fortune out of the above disc, as did she and Mr Handy.

There have been thousand of recordings since, to the point where "Saint Louis Blues" was for many years the second most recorded song of all time after "Stardust". When British prime minister Ramsay MacDonald first visited the United States, his hosts chose this song to play to him as representative of distinctively American music. But it has its admirers on the PM's side of the ocean, too: in 1934, when Prince George, father of the present Duke of Kent, married Princess Marina of Greece, this was the song they danced to at their wedding; it was also one of the Queen Mother's favorites. And in the 1930s it was a much played battle hymn of the Ethiopian Army.

Re those last enthusiasts, one can't but wonder if Emperor Haile Selassie's chaps wouldn't have done better against the Italians had they gone into battle playing this most famous of all the novelty re-interpretations of the song. The arrangement, for Glenn Miller's Army-Air Force Band, is mostly Jerry Gray's (with a few helping hands), and over the decades I have never met a US veteran stationed in England in those pre-D-Day years who, whatever his antipathy to marching more generally, did not enjoy the particular swagger of this - one of the handful of records that for me will always be the sound of America at war:

"The Saint Louis Blues" was written in 1914, the age of mawkish ballads ("You Planted A Rose in the Garden of Love") and crackpot novelty songs ("Fido is a Hot Dog Now"). Nonetheless, a fair old few hits have sort of survived from that year: "The Aba Daba Honeymoon", "Too Ra Loo Ra Loo Ral (That's an Irish Lullaby)" and "They Didn't Believe Me". That last one certainly had a greater impact on the evolution of the American songbook, but the one we're celebrating today was a much bigger hit.

Its composer and lyricist, William Christopher Handy, was heavily promoted as the "Father of the Blues", but in his own recitation of the facts preferred to present himself as more of a midwife, responsible for delivering the blues and then popularising them across America and the world. He was born in the little town of Florence, Alabama on November 16th 1873, not poor and downtrodden but a part of the Negro bourgeoisie that briefly flourished in the Reconstruction era and which intriguing demographic has been largely written out of the American story. W C Handy was the son of a black minister who considered secular music immoral. But one day, as a young boy, William Chritopher was given a trumpet by a visiting circus performer, and soon after, in defiance of his parents, he joined a traveling minstrel show. When the show failed, he took up teaching and then worked in a foundry, where he started an amateur brass band. From then until he wrote this blockbuster hit, his career was a succession of ups and downs: He certainly knew what it was like to have the blues - but, to modify the old line on lemons, when life hands you the blues, make the blues sing:

That's the marvelous Maxine Sullivan, who many years later sang me a few bars of that at what I recall as a far swingier clip.

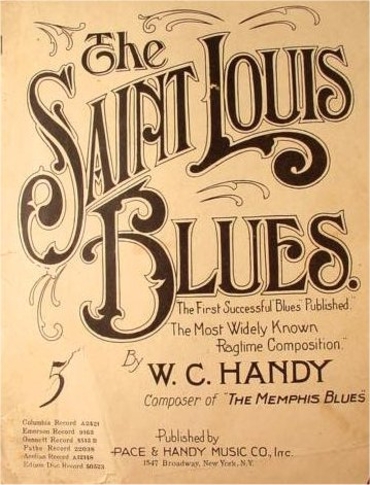

W C Handy first heard the blues in 1892, when he was sleeping on the cobblestones of one of the Mississippi River's great towns. But he didn't really get hooked, until one night, playing with his band in Cleveland, Mississippi, he saw a local group get more money for one blues number than his boys earned for the whole evening. Handy was converted. In 1912 he wrote his first hit, the first big-selling blues, "The Memphis Blues", but he was foolish enough to sell it outright for a mere fifty dollars. He was determined not to make the same mistake with his next song. The reason we know his name today his because, unlike many other black writers of the period, he figured out the business of publishing and copyrights and intellectual property rights.

At this time, Handy actually lived in Memphis and played in a club on Beale Street, an historic thoroughfare in the annals of jazz and one which Handy himself would later pay tribute to in "The Beale Street Blues". He was by trade a composer and a lyricist - that's to say, he wrote words and music for what he hoped would be hit songs. Yet, whenever he talked about his songs, there wasn't a lot of "composition" - there would merely be strains in the air, vernacular themes dimly recalled. Perhaps he was more like his very proper preacher father than he knew, but he preferred to present himself more as an anthropologist of the blues than as a writer thereof. He was also a very exhaustive memoirist, who spent more time writing about these songs than he claims to have spent writing the songs themselves. And so, by Handy's own account, we can pinpoint the birth of "The Saint Louis Blues" to one night in September 1914. That evening he left his wife and family and rented a room on Beale Street in which to work.

"Outside, the lights flickered," he wrote in his autobiography. "Chitteling joints were as crowded as the more fashionable resorts like the Iroquois." The Chitlin' Circuit were the separate venues for colored entertainers required by segregation, and endured until the Sixties. As Handy continued, "Piano thumpers tickled the ivories in the saloons to attract customers, furnishing a theme for the prayers at Beale St. Baptist Church... Scores of powerfully built roustabouts from river boats sauntered along the pavement, elbowing fashionable browns in beautiful gowns. Pimps in boxback coats and undented Stetsons came out to get a breath of early evening air and to welcome the young night. The poolhall crowd grew livelier than they had been during the day. All that contributed to the color and spell of Beale Street mingled outside, but I neither saw nor heard it that night. I had a song to write." That's an awful lot of detail for something he "neither saw nor heard", but, as I said, few songwriters have ever written more about writing their songs.

Besides, Handy's thoughts were drifting away from Memphis to a town he had wandered through a few years earlier. On the levee there, he had heard the roustabouts singing a number called "Looking for the Bully". If you've never heard of that song, well, here it is:

W C Handy wanted a success like that, but one which expressed real emotions, true to the soil and in the blues pattern. He decided to begin with a downhome ditty "fit to go with twanging banjos and yellow shoes... A flood of memories filled my mind. First, there was the picture I had of myself, broke, unshaven, wanting even a decent meal, and standing before the lighted saloon... without a shirt under my frayed coat.,." During his destitute period in that Mississippi town, he had seen a grieving woman, drinking heavily. "Stumbling along the poorly lighted street, she muttered as she walked; 'Ma man's got a heart like a rock cast in de sea...' My song was taking shape. I had now settled on the mood..."

See what I mean? "Ma man's got a heart like a rock cast in de sea": What a great line - but no, the supposed composer never actually composed it, he just eavesdropped on a gibbering passer-by.

Earlier memories contributed too. From 1896 to 1900 Handy had worked as a bandmaster in Henderson, Kentucky, whose other great musical alumnus is Grandpa Jones of "Hee Haw" fame, and whose principal non-musical claim to fame is the painter and naturalist John James Audubon. On my only ever visit to Henderson, I recall a municipal swimming pool named for W C Handy, which I trust survives. Handy's own memories of the town included an "odd gent who called figures for the Kentucky breakdown ...the one who everlastingly pitched his tones in the key of G". So there was Handy's key. His song had four sections and fifty-two measures in all: Three twelve-bar blues passages, and as his release a sixteen-bar section quite unlike any other vernacular twelve-bar blues and indeed unlike any other popular song of the period. According to Handy, the tango was originally an African jungle dance, the tangana. The Moors brought it to Spain, and Negro slaves took it to Cuba, where it became the habanera (as in the famous aria from Carmen, "L'amour est un oiseau rebelle"). Although it was the Argentines who refined this dance into the more sensual tango, it was, per Handy, also a part of Negro life on the Mississippi. The sixteen-bar passage certainly makes the piece more varied than other blues, although over-emphasizing the Latin rhythms is, I feel, ill-advised, and those who do so often come a cropper (see Perry Como's version).

The final blues strain of the song goes back to W C's childhood and (here we go yet again with Handy the musicologist rather than Handy the composer) a chant used by Elder Lazarus Gardner as he took up the collection at the African Methodist Episcopal Church of Florence, Alabama. In fact, the only bit of creative activity Handy would admit to was the first line:

I hate to see de evenin' sun go down...

As he later wrote, "If you ever had to sleep on the cobbles down by the river, you'll understand that complaint."

By now the night was over. Handy named the song after the town which had inspired it, and went down to Pee Wee's saloon, a musicians' hangout at 317 Beale Street. Propped up at the cigar stand, he spent the day orchestrating his song until, bleary eyed with lack of sleep, he went to his band's evening engagement. Afterwards, the boys went back to Handy's home to celebrate. Unfortunately, he'd neglected to tell his wife he'd be away for twenty-four hours, and she was waiting for him with a rolling pin in his arm. "Maybe," Handy admitted, "I should have stated where I was going... But it's an awkward thing to announce in advance your intention of composing a song hit between midnight and dawn..."

Handy thought he had a hit ...and then found he couldn't interest a single music publisher in his new song. Eventually, he decided to publish it himself, which proved to be a very shrewd move. Prince's Orchestra made a record of it in 1916 and Al Bernard, "The Boy from Dixie", made another a couple of years later, and Sophie Tucker sang it in vaudeville, and by the time Marion Harris made the hit record we started with it was clear that Handy had written himself a lifetime insurance policy. Within a few years, every recording and piano roll company had issued the song; within a few more years, Handy was receiving an annual royalty of $25,000. The poverty of his early career, which had inspired the song, was behind him forever.

It has lapsed a little in recent decades, and, from my own unscientific survey, seems increasingly the preserve of Dixieland and trad jazzers. But let me offer a few recordings that exemplify its range from some old pals of mine. Here is Russell Malone, a big part of last year's Mark Steyn Christmas Show (which, seven months into lockdown, is looking like the last Christmas show we'll ever be permitted to do). This is a lovely unmannered version:

And here, by way of contrast, from around the same time (the early Nineties) is Cleo Laine. I knew a certain British bandleader who'd auditioned young Cleo round about 1950, and turned her down. "Why was that?" I asked. "I couldn't understand a word she was singing," he said. I can sort of see his point: She has a very distinctive tone that sometimes swallows consonants. But she's on top of this one, and living the lyric:

And finally I mentioned, à propos the Glenn Miller arrangement above, that there had been many novelty interpretations of the song. This wasn't as big as "The Saint Louis Blues March", but it tickled the lower end of the hit parade as a modest beneficiary of the mambo craze of the mid-Fifties. The first ever book I wrote (at the invitation of Cameron Mackintosh) was about the making of the musical Miss Saigon. So for a while I spent a lot of time in the company of the show's English-language lyricist, Richard Maltby Jr. Richard is a successful writer and director and cryptic-crossword deviser for Harper's. His dad, Richard Maltby Sr, had his own orchestra in the post-war years, and this cute couple minutes gave him his first Top 40 hit:

"The Saint Louis Blues" was such a hit that it never really mattered that its author could never quite match it. It was deployed as the only possible title for W C Handy's biopic, starring Nat King Cole and openeing ten days after Handy's death in 1958. Twenty years earlier, W C Handy had been given a sixty-fifth birthday tribute at Carnegie Hall, which included a song written in his honor by J Fred Coots (of "Santa Claus is Coming to Town") and Benny Davis (of "Baby Face"). They called their tribute number "Thanks to You, Mr Handy, for Giving Us The Saint Louis Blues".

Indeed. Thanks to you, Mr Handy. Here's Nat as the "Father of the Blues", dressed as its composer was wont to garb himself for musical soirées. White tie, black tails, blue as only a man who hates to see the evening sun go down can be:

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Ted Nugent, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Paul Simon, Lulu, Tim Rice and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.

Our Netflix-style tile-format archives for Tales for Our Time and Steyn's Sunday Poems have proved so popular with listeners and viewers that we've done the same for our musical features merely to provide some mellifluous diversions in the Land of Lockdown. Just click here, and you'll find easy-to-access live performances by everyone from Herman's Hermits to Liza Minnelli; Mark's interviews with Chuck Berry, Leonard Bernstein and Bananarama (just to riffle through the Bs); and audio documentaries on P G Wodehouse's lyrics, John Barry's Bond themes, sunshine songs from the Sunshine State, and much more. We'll be adding to the archive in the months ahead, but, even as it is, we hope you'll find the new SteynOnline music home page a welcome respite from house arrest without end.

If you're a Mark Steyn Club member and the above column brings on the blues, feel free to start a-wailin' in our comments section. As we always say, membership in The Mark Steyn Club isn't for everybody, and it doesn't affect access to Song of the Week and our other regular content, but one thing it does give you is commenter's privileges. Please stay on topic and don't include URLs, as the longer ones can wreak havoc with the formatting of the page.