The mile-long list of People I Can't Be Friends With includes, somewhere near the top, That Guy Who Says, "You Gotta Watch That Movie Stoned." If you have to get drunk or high to watch a certain movie — 2001, El Topo, a selection from the Troma catalog — there is something wrong with you, that movie, or both.

A more sublime experience? A movie that is the drug, that temporarily alters one's nervous system. One for which the expression "mind blowing" was minted. Stendhal Syndrome cinema.

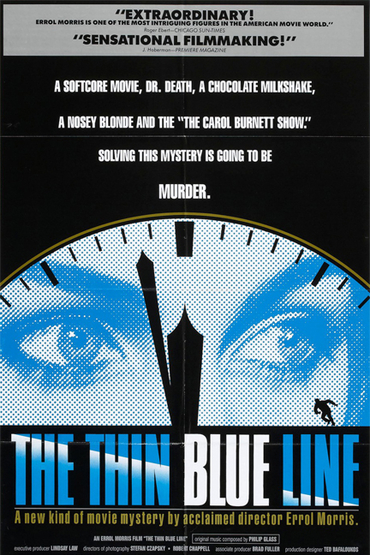

That's how I felt the first time I saw Errol Morris' documentary The Thin Blue Line, shortly after its 1988 release.

Morris' first documentary, 1978's Gates of Heaven, was "about" two rival pet cemeteries — a kind of American Way of Death but with cats and dogs. Morris' friend, director Werner Herzog, told Morris he would eat his shoe if his buddy's movie ever got screened in a theater, let alone completed. The famed German filmmaker was obligated to make Werner Herzog Eats His Shoe two year later, because not only did Gates of Heaven get made and distributed, but none other than Roger Ebert declared it one of the ten best films of all time.

Despite that and other accolades, Morris eventually found himself unable to get funding for another project.

Flailing around for subject matter — while supporting himself as a private detective — he settled on a Texas psychiatrist dubbed "Dr. Death."

The state employed Dr. Death specifically to "examine" accused murderers (sometimes for only a few minutes), then declare them "likely to reoffend," thereby ensuring they'd receive the death penalty.

While researching this project, Morris interviewed Texas death row inmates who'd been Dr. Death's "patients." He knew going in that most would plead their innocence, but one prisoner seemed sincere. Morris, a self-described obsessive, became haunted by his case.

Randall Adams, an itinerant workman with no criminal record, had been convicted of slaying a Dallas police officer during a traffic stop in 1976. Adams insisted that the real culprit was a juvenile delinquent and runaway he'd befriended that day, David Harris, who was (very) well-known to police in his native Vidor, Texas.

The evidence against Adams was shaky, but the animus against him by police and the district attorney was not. Morris came to suspect they'd set their sights on Adams because — in an echo of the infamous British "Let him have it" case — Adams happened to be the older of the two men, and therefore more likely to be sentenced to death in a jury trial.

Predictably, The Thin Blue Line includes interviews with Adams, Harris, the judge, Adams' lawyers, three "witnesses," and Dallas police officers. (Since this is the same force that brought you the Lee Harvey Oswald prison transfer, you may be unsurprised to learn that the Dallas PD doesn't exactly cover themselves in glory here.)

But there is much more:

Violating the cardinal rules of the documentary catechism, Morris staged re-enactments of the crime, Rashomon-esque sequences that act out everyone's conflicting narratives about what happened on the side of that Texas road.

The Thin Blue Line has no narrator, either. Morris rejected the snobbish received wisdom that serious documentaries needed them — or even those on-screen "lower thirds" identifying the person being interviewed.

He also tossed aside the deeply ingrained notion that non-fiction films with serious "social justice" agendas needed to be grainy and gritty, shot shakily with handheld cameras, cinéma verité style, in the manner of canonical works like Titicut Follies and Harvest of Shame.

"There's this false idea that style equals truth," Morris said later. "If you adopt a certain style, out pops truth. It's a stupid idea. Truth isn't guaranteed by style. Truth, to the extent that we can ever grab hold of it, is the product of a lot of hard work and investigation."

The Thin Blue Line is a slick and shiny slow drip of a movie, each drop of evidence dancing with one of the most felicitous, insinuating scores in cinema history, composed by Phillip Glass.

Harlan County, USA it ain't.

Violating these documentary commandments cost Morris an Oscar nomination in that category, but not a brace of other awards — and certainly not buzz: Purists were aghast, but their voices were quickly smothered by critics and civilian cineastes. Just plain folks who'd never bought a movie ticket for a documentary before flocked to theaters.

Then something incredible occurred:

The Thin Blue Line was so widely-seen, discussed and debated that it refocussed attention on Randall Adams' conviction. The following year, he was exonerated. Adams walked out of prison after 12 years — and The Thin Blue Line entered the very canon it had rebelled against, as not only one of the most visually and aurally innovative, but also most undeniably effectual, documentaries in history. (Take that, Michael Moore...)

In yet another, sadder twist, Randall Adams later sued Morris for the rights to his life story, a suit that was settled in 1989. Adams died of a brain tumor in 2010; his nemesis, David Harris, was executed in 2004 for an unrelated crime.

I won't lie: Looking back, I sense that some of The Thin Blue Line's appeal for what we'd now call Blue State audiences was the film's Texas setting, at a time when "Dallas" was still a byword for "murder." I'm fairly certain it wasn't Morris' intention — and in this he also departs from his filmmaking brethren, despite sharing their left of center worldview — but the film gives off that "Let's go laugh at the hicks!" odor that makes liberals salivate. Oh, those "funny" accents! The "white-trashiness" of it all! Morris' pointing out that Vidor is "the headquarters of the KKK," while not gratuitous, was the juicy cherry on top of this fly-over sundae.

A unique art object, ironically, impels us to resort to cliches like "jaw dropping" and, yes, "mind blowing," when attempting to describe it, so bereft are we for fitting descriptors. I regularly turned to the person watching The Thin Blue Line with me that first time, and he kept turning to me, in shock. Between the music, the narrative, and the sophisticated visuals, we had never seen a documentary like this in our ever-lovin' National Film Board of Canada lives.

The other problem with "unique," besides the fact that the word is too frequently (mis)used? At least in the case of Morris' masterpiece, the adjective rapidly became inapt: Almost immediately, other filmmakers felt empowered to break out of the old-fashioned documentary mode, too, and television adopted Morris' signature style for true crime, "magazine" style shows like 48 Hours and Dateline. The same year The Thin Blue Line came out, America's Most Wanted, with its uncanny re-enactments, began its 25 season run.

As the ultimate tribute, the ingenious Documentary Now! gang chose The Thin Blue Line for one of their exquisite parodies. (How could they not?)

As I mentioned in a previous column, they managed to rent the same camera lenses Morris did, from the same small photo equipment supplier, to craft their painfully precise spoof, The Eye Doesn't Lie.

Recently, a much-younger colleague asked me to recommend a classic documentary. Of course, I mentioned The Thin Blue Line, but warned her that she would probably get to the end and shrug, "So what?" After all, throughout her adult life, Morris' once innovative style had become ubiquitous. His "Mona Lisa," as it were, now adorns coffee mugs and fridge magnets.

And when re-watching the film for this column, I didn't re-experience the magical sensation I'd felt that night in 1988. The movie had lost what Walter Benjamin called its "aura". Knowing that Adams was eventually released reduces much of the tension and outrage Morris builds up so carefully. My frustration with the film's blatantly awful bad guys came to a simmer, not a boil. And the colors had faded somehow.

That's the trouble with a drug: You never quite feel that first high again.

~Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think of this column by logging into SteynOnline and sharing below. Membership in the Mark Steyn Club has many perks, from commenting privileges, to access to the entire SteynOnline back catalog, to exclusive invitations to Steyn events. Take out a membership for yourself or a loved one here. Kick back with your fellow Club members in person aboard one of our annual cruises. We've rescheduled our Mediterranean voyage to next year, but it's sure to be a blast with Douglas Murray, John O'Sullivan and Tal Bachman among Mark's special guests.