In this contribution, I take a break from chronicling The End of the World to remember the passing of a musical icon forty years ago this past week...

The song grabs you in the first two seconds: two shots on an E chord, followed by quarter-note hi-hat hits. You know something big's going to happen. No—it already is happening.

At five seconds, the hi-hat hits double into eighth-notes as the E chord shots repeat. At seven seconds, the addition of a swung sixteenth-note (played on cowbell with a brush) signals the imminent, exhilarating plunge into a song you've never heard, but which you now want to hear more than anything else.

And at twelve seconds, an authoritative, effortlessly-executed drum fill plunges you into what might be rock and roll's greatest first song on a first album, ever...and we already know—before the song, or even a proper drum part, has started—we're in the presence of drumming greatness. The rest of the song, as well as the rest of the album, only further confirms it.

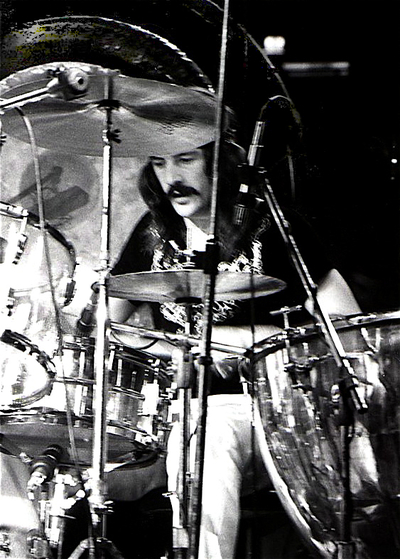

The song is "Good Times, Bad Times". The album is Led Zeppelin I, released in early 1969. And the drummer was a scrawny, twenty year old Brummie who'd never taken a drum lesson in his life. For the next twelve years, John Bonham would power the biggest, most influential, most iconic rock band in history, until his premature death forty years ago this past week. Even now, all these years later, ask any rock musician who the greatest rock drummer in history is, and almost all will name Bonham. Here's why.

Think about any musical contender for the "greatest" something or other—singer, guitarist, saxophonist, etc.—and you'll notice that underneath all the differences in style, they were all great musicians first.

After all, you're not "the greatest rock guitarist ever" if you can merely play faster than everyone else, or the greatest singer because you can perform the most vocal acrobatics. The particular skills themselves are not the end; they are the means. The end is the creation of a powerful, moving, shared, binding, emotional/psychological/spiritual experience through music. Teleologically speaking, your role as a musician is shamanic, not self-serving or exhibitionist: you're creating a magic spell for everyone through your musical skills.

So the first thing to say about Bonham is that he was rock's greatest drummer because he was one of rock's greatest musicians. He understood songcraft. He understood dynamics and drama and flow. He could sense, and tap into, and express, the spirit of any number. He listened to, locked in with, the other musicians he played with, as a fellow ensemble member.

In short, he was a great musician who happened to play drums. Certainly he possessed prodigious technical skills on his chosen instrument—picked up after an adolescence spent listening to jazz drummers Gene Krupa, Max Roach, and Buddy Rich. But Bonham deployed (or didn't deploy) his skills in just the way each piece of music (each unique, shamanic, musical spell) asked. To put it in automotive terms (which auto-racing-fanatic Bonham would have loved), he had a lot of gears, and always knew exactly how to use them.

And that is why you can hear adrenalized razzle-dazzle on "Good Times, Bad Times", "Rock and Roll", or "We're Gonna Groove"; jazzy, dynamic, drama on "Since I've Been Loving You" or "I Can't Quit You"; stolid, rolling snare throughout all of "Poor Tom"; titanic, Valhallian pounding on "In My Time of Dying"; expansiveness on "In The Light"; hypnotic repetition on "When the Levee Breaks", "Four Sticks", or "Kashmir"; something like levity on "The Ocean", and dozens of other shifts in approach, all dictated by the spirit of each number, but all underpinned by a concrete solidity.

But solidity wasn't the only constant. There was also a unique, even idiosyncratic, drum kit sound which remained the same on every recording Led Zeppelin ever made.

I say Bonham's drums sounded unique to the point of idiosyncrasy; they did, but I should qualify that. They didn't sound like any of his contemporaries's drums: not Ginger Baker's, not Ringo Starr's, not Mitch Mitchell's, and certainly not Keith Moon's. For people who only listened to pop or rock, Bonham had a sound all his own.

But a jazz aficionado would have told you something different: Bonham's kit sounded a lot like Buddy Rich's. Somehow or other, the young Bonham had figured out how Rich tuned his snare and toms—a technique which focused on tension (not tuning to particular pitches), cranked the resonant-head tension unusually high, and mostly avoided dampeners—and used the same technique on his own kit. (Compare the similarity in drum sound [and even playing] between this Buddy Rich solo and this Bonham solo).

Bonham's twist was to retain Rich's tuning techniques, while adapting some of Rich's trademark techniques (like the sixteenth-note triplet), using bigger drums, and adding extra patterns and gears to his repertoire. (As fantastic a drummer as Buddy Rich was, it's impossible to imagine him ever locking into anything as simple or heavy as Bonham's groove on "When the Levee Breaks", let alone staying there for seven minutes.)

Add that all together, and you have a drummer who, upon the release of Led Zeppelin I, goes from entirely obscure to an electrifying force demanding attention—so much so, that even then reigning musical gods The Beatles and Jimi Hendrix begin raving about him—and then remains just that for the next half century, including forty years after his death on September 25, 1980, at the age of only 32.

The official verdict was accidental death due to pulmonary asphyxiation: Bonham fell asleep after a day of excessive drinking during band rehearsals, and after vomiting in his sleep, never woke up again. Knowing that without Bonham, there could be no Led Zeppelin, the three remaining band members dissolved the band shortly thereafter.

John Bonham left behind a wife, Pat, and two children, Jason and Zoe, as well as an amazing musical legacy for every aspiring musician and drummer. He's gone now, but if the past half century is any guide, that legacy will live on forever.

RIP always, John Bonham.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Tal Bachman know what they think by logging into SteynOnline and hitting the comments section. Commenting privileges are just one of many perks that come along with Mark Steyn Club membership, including access to members-only events, Steyn Store discounts and an all-access pass to SteynOnline's audio, video and written content. Kick back with Tal and Mark's other special guests, such as Michele Bachmann and Douglas Murray, in person aboard next year's Mediterranean Mark Steyn Cruise.