Sixty-five years ago - September 1955 - America was reeling under one of those blockbuster Number Ones, so blockbuster indeed that it toppled "Rock Around the Clock" from the top spot. What does it take to knock off rock's first great iconic anthem? A beautiful Sinatra love ballad? A showstopping Rodgers & Hammerstein eleven o'clock number? Not a chance: To see off Bill Haley, all it takes a century old folk-song, heavy on the snare drums. And next thing you know you're blasting from every radio and jukebox:

Mitch Miller was a prodigious hitmaker of the early Fifties, but credit where it's due: That particular smash starts with a fellow called Bill Randle who, one day in 1955 suggested to the songwriter Don George that a relatively minor folk song might have the makings of a pop hit. Randle is an obscure figure now but back then he was a bigshot Cleveland disc-jockey who cut an impressive swathe in the music biz. A man with an eye for up and coming talent who played a role in advancing the careers of Tony Bennett, Bill Haley and Elvis Presley, Randle also had a good sense of more idiosyncratic possibilities: He was the guy who suggested the whiter-than-white Crew-Cuts should cover a black "race records" song, "Sh-Boom".

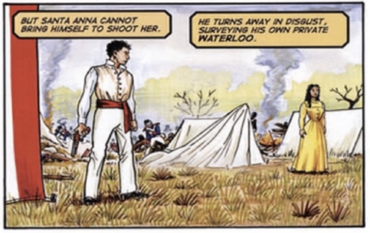

So, when Randle drew Don George's attention to an old Civil War song, his songwriting friend listened. By that stage in his life, George was a respected Tin Pan Alley journeyman, a man who made a nice living writing special material for Nat King Cole and others but not a consistent hitmaker. The song Randle wanted him to take a look at had its origins in one of the decisive engagements in the Texan war of independence, the battle of San Jacinto back in 1836. In its earliest version, it purported to tell the story of a woman named "Emily Morgan" or "Emily West" who entertained the Mexican general Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana so exhaustively in his tent on the day of the battle that he was too distracted to pay attention to military matters and thus the Texan troops caught him unawares. He was obliged to flee without armor or weapons and was easily captured within twenty-four hours.

"Emily Morgan" was supposedly a mulatto slave belonging to Colonel Morgan of New Washington, Texas. The real-life Emily West was a free black woman employed as a housekeeper in the New Washington Association's hotel. They may conceivably be the same woman, but, in any case, there's no evidence that one or other seduced General Santa Ana on the big day. The legend seems to be little more than a Texan variant of Judges 4, verses 14-22, but for a while it had some appeal to Texans and lingered in the folk memory. From an adaptor's point of view, the key word is "mulatto":

There's a yellow rose in Texas

That I am goin' to see

No other darkie knows her

No darkie, only me...

Thus, the Yellow Rose of Texas - as in a "high yaller", a light-skinned Negro woman. Revolutions and their legends come and go but love songs are forever, and, as Emily and General Santa Ana faded, "The Yellow Rose Of Texas" settled down as a more general plaint of a black man for his sweetheart:

She's the sweetest rose of color

This darkie ever knew

Her eyes are bright as diamonds

They sparkle like the dew

You may talk about your Dearest May

And sing of Rosa Lee

But The Yellow Rose Of Texas

Beats the belles of Tennessee...

"Dearest May" and "Rosa Lee" refer to two other paeans to fair maidenhood, though both were songs for minstrels in blackface - which suggests that either "Yellow Rose" was written by a white man or that its Negro author is hymning his gal as the real deal rather than a mere confection of minstrelsy. At any rate, the song underwent another transformation come the Civil War, when Confederate troops turned it into a tribute to General John Hood:

Oh, my feet are torn and bloody

My heart is full of woe

I'm going back to Georgia

To find my Uncle Joe

You may talk about your Beauregard

And sing of General Lee

But the gallant Hood of Texas

Played hell in Tennessee...

And thereafter the song lapsed back into non-topical semi-obscurity. In 1930, the Texas cowboy composer David Guion wrote his own transcription of the number from memory, as he did with a number of other songs: It was Guion's version of "Home On The Range", for example, that established the song in the version we know it today. And so for the next quarter-century an anachronistic Negro folk song enjoyed a decent living as a loping western ballad from the likes of Roy Rogers, and Gene Autry:

At which point, enter Bill Randle and Don George. George de-racialized the song, and what emerged was a more or less conventional valentine with a few Lone Star touches:

When the Rio Grande is flowing

The starry skies are bright

She walks along the river

In the quiet summer night:

I know that she remembers

When we parted long ago

I promise to return again

And not to leave her soShe's the sweetest little rosebud

That Texas ever knew

Her eyes are bright as diamonds

They sparkle like the dew

You may talk about your Clementine

And sing of Rosa Lee,

But The Yellow Rose Of Texas

Is the only girl for me...

Don George was a savvy Tin Pan Alley professional: "You may talk about your Dearest May", but let's face it very few of us do. "Dearest May" was an almost entirely forgotten song by 1955, but "My Darling Clementine" was still in circulation and did the trick just as well (and was even better known a few years later when Bobby Darin's revival made it a monster hit). Of course, now that the "yellow rose" is no longer a "yaller" colored woman but just any old gal, the title doesn't really make a lot of sense. But nobody minded, not once Mitch Miller was through wioth it. What made the song was his über-martial arrangement, heavy on the snare drums. The snare drum had been around for half a millennium, but in the record biz it was a novelty: Before Miller it had never occurred to anybody to build an arrangement around it. Mitch went into the studio and so liked what he came out with he ordered an initial pressing of 100,000 singles. When one of his bosses at Columbia objected to the size of the order, Miller offered to buy back any unsold copies with his own money. He never had to. On September 3rd 1955 "Yellow Rose Of Texas" knocked "Rock Around The Clock" off the Number One spot, and was on its way to million-seller status.

As for the snare drums, Stan Freberg's parody version - with Stan battling an over-enthusiastic snare man - had the last word on that:

That's Billy May's band with Stan, and, as Billy told me years later, he and the musicians had great difficulty playing with a straight face. The snare drum became standard in the rock'n'roll era, but Mitch Miller got there first. He was a musician of great skill and no taste, but he knew what he was doing.

Don George is nobody's idea of a household name. Born on August 27th 1909 in New York, he has his name on a few hemi-demi-semi-standards ("I Ain't Got Nothin' But The Blues") but his reputation and his royalties rest on two hits as different as any pair of songs could be. And, when the first is "Yellow Rose of Texas", it seems a bit unfair not to tip one's hat to the second. Don George's other big song was a collaboration with a bandleader who's as close to the precise opposite of Mitch Miller as one could devise: Duke Ellington. Yet it started in much the same way - with the vague sense that there might be a pop hit in something that had never been intended as such. In 1944 - eleven years before "Yellow Rose Of Texas" - George found himself mesmerized by a throwaway musical phrase Ellington's saxophonist Johnny Hodges used to play to get in and out of solos. "That's a hell of a line," Don said to Duke. "It could be a hit."

"You think so?" said Ellington. "Let's get with Johnny and work it out." So Hodges, Ellington and George got together and extended the transition phrase into a melody in classic A-A-B-A pop song form. And, when they'd finished, Johnny and Duke turned to Don and said, "Okay, so what's the title?"

"Don't worry," he told them, "I'll come up with something." Easier said than done - until one day, whiling away the afternoon at the Paramount Theatre in New York, he chanced to catch a short film just before the main feature. It was about a revival meeting in the south, in a packed tent with a charismatic preacher. And at one point one of his parishioners - a large lady shaking all over and rolling her eyes - stood up in the aisle and roared, "I'm beginning to see the light!" After which she fainted and hit the floor.

Don George nearly did the same. But he held himself together, rushed out of the theater, found Ellington rehearsing the orchestra and yelled, "Hey, Duke, we've got a title." Not just any old title, but one that George deployed to drive the entire lyric:

I never cared much for moonlit skies

I never winked back at fireflies

But now that the stars are in your eyes

I'm Beginning To See The Light ...

In his book The House That George Built, the late Wilfrid Sheed has an interesting discussion on Ellington the songwriter. It's not necessary to agree completely with his assertion that jazz is "not in its heart a singing medium" to appreciate that he's right about the way many jazz vocalists distance themselves from the lyric. Hence, scat. Writes Sheed:

Use the human voice purely as an instrument, and make clear that that's what you're doing. Jazz tells its own stories. It doesn't need words, and scat is simply jazz's way of saying, 'Get lost.'

But Duke's music seems to defy scat, too. Scat "Mood Indigo" or "Sophisticated Lady"? Whatever they are, Ellington's compositions are not songs in the sense of words and music achieving a unity that makes each contribution eternally present within the other: You can't hear an orchestra play "Ol' Man River" without being aware of Oscar Hammerstein's words or see a quotation from the lyric without hearing Jerome Kern's tune. There's none of that in, say, "Prelude To A Kiss", in which, its words notwithstanding, there isn't anything the singer's singing that, as Sheed puts it, "wouldn't sound better played on something else". Perhaps because it started with Johnny Hodges and was never conceived as a "composition", "I'm Beginning To See The Light" is a rarity - an Ellington song that sounds like it was meant to be a song.

From a lyricist's perspective, it's a perilous piece. If the first line doesn't automatically sound like a vamp, it does by the time you've heard it three times. George chose to emphasize its monotony with a three-way rhyme scheme leading up to the title phrase. It's the simplest idea - lights of all kinds. Moonlit skies, fireflies, stars in your eyes and then:

I never went in for afterglow

Or candle light on the mistletoe

But now when you turn the lamp down low

I'm Beginning To See The Light...

For the middle-eight, George opted for another three-way rhyme scheme that cranks up the illuminatory imagery into something more incendiary:

I used to ramble through the park

Shadow boxing in the dark

Then you came and caused a spark

That's a four-alarm fire now...

Easier sung than done. For whatever reason, Duke cooled on the song - perhaps because it was all too obviously a song rather than an Ellington masterpiece on which some opportunist had hung words. "Give it up," Duke advised Don George. But he couldn't. "Of all the songs I'd written," he said, "this one kept walking back and forth through my mind."

He wasn't a wealthy man. He was just getting started in the business. But he borrowed some money for a train ticket to California, and made a few calls. He got in to see Johnny Mercer at Capitol Records. Mercer liked the title but told him the tune was boring and then snered, "C'mon, Don. How about that lyric?" That goofy laundry list of luminescent imagery? Forget it.

It was the same everywhere he went - until, finally, another bandleader, Harry James, agreed to record the song in exchange for a co-author credit. So, if you glance at the credits and wonder how it was that Duke Ellington and Harry James came to co-compose a tune together, well, they didn't. The bandleader who co-composed it didn't like it enough to play it. But the bandleader who had nothing to do with its composition was nevertheless willing to perform it:

The James version with Kitty Kallen's vocal went on to sell a million copies, and after that Ellington saw the light - and so eventually did Johnny Mercer. Running into Don George in a bar, Mercer demanded to know why George had never brought the song to him. Sinatra made a terrific record of it with Neal Hefti, and so, as demonstrated above, did Bobby Darin as part of his post-"Mack The Knife" reinvention as Mister Finger-Snappy. And since then the song's never gone away.

Thus, Don George's two big hits: one, a defining example of Mitch Miller novelty singalong light music; the other, also "light music" - or, at any rate, music with a lyric about lights. "Yellow Rose Of Texas" made him more money at the time, but "I'm Beginning To See The Light" was the song he loved - and the real enduring standard:

I never made love by lantern shine

I never saw rainbows in my wine

But now that your lips are burning mine

I'm Beginning To See The Light.

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Ted Nugent, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Paul Simon, Lulu, Tim Rice and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.

Our Netflix-style tile-format archives for Tales for Our Time and Steyn's Sunday Poems have proved so popular with listeners and viewers that we've done the same for our musical features merely to provide some mellifluous diversions in this age of lockdown and looting. Just click here, and you'll find easy-to-access live performances by everyone from Liza Minnelli to Loudon Wainwright III; Mark's interviews with Chuck Berry, Leonard Bernstein and Bananarama (just to riffle through the Bs); and audio documentaries on P G Wodehouse's lyrics, John Barry's Bond themes, sunshine songs from the Sunshine State, and much more. We'll be adding to the archive in the months ahead, but, even as it is, we hope you'll find the new SteynOnline music home page a welcome respite from house arrest without end and revolution on the streets.