In synopses of pre-war Hollywood comedies, the word "heiress" was rarely unaccompanied by the adjective "madcap." So-called "screwball" farces — It Happened One Night, My Man Godfrey, Bringing Up Baby and The Philadelphia Story — frequently featured a "poor little rich girl" blithely indulging in eccentricities that no lower class woman could get away with without being beaten or locked up: traipsing across the country, smashing expensive stuff, undoing other people's well-laid plans.

(And while she exists in a different genre and decade altogether, as Camille Paglia notes sharply, Tippi Hedren's San Francisco newspaper heiress in Hitchcock's The Birds belongs to that "screwball" tradition: spoiled, headstrong, leaving destruction in her wake.)

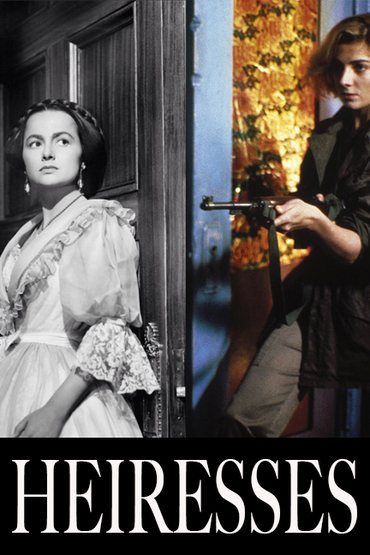

Today's two movie heiresses, on the other hand, offer studies not in anarchic independence, but forceable confinement, at least through most of their running time.

William Wyler's The Heiress (1949) was based on Henry James' Washington Square (or, more accurately, the hit play adapted from that novel by Ruth and Augustus Goetz.)

In mid-1800s New York City, timid, plain Catherine Sloper (Olivia de Havilland) is a profound disappointment to her wealthy widowed father, Dr. Austin Sloper (Ralph Richardson), who routinely compares her unfavorably to her graceful, gorgeous mother.

(In the novel, Mrs. Sloper died giving birth to Catherine, but Dr. Sloper's resulting resentment of his daughter isn't foregrounded in the film.)

An unflattering hairstyle and "no-makeup" makeup render the lovely de Havilland passably homely — I find her look here more convincing in that respect than many critics; she's quite Emily Dickenson-esque — but it's obvious to any post-Freudian viewer that whatever Catherine's natural charms, or lack thereof, her shyness and clumsiness are the predictable and ironic result of her father's constant badgering about those very traits.

At a dance, Catherine is singled out for attention by Morris Townsend (Montgomery Clift.)

He's preternaturally handsome, soft-spoken and gracious, and while he's a member of her class, he's also broke, having frittered away his inheritance. They pledge their love, but Catherine's father is understandably suspicious of the young man's intentions: After all, his daughter, who already has an income of $10,000 a year from her late mother, will inherit another $20,000 annually upon his death. That is, unless he disinherits her should she marry Townsend.

I don't want to ruin The Heiress for those who haven't seen it — and you really must — so I'll just say that de Havilland's Oscar was well-deserved. Wounded again and again by the two men in her life, Catherine subtly morphs from feeble to quietly ferocious. Along with adopting a deeper, steadier voice, I suspect that de Havilland was made to wear a touch more makeup in the third act, as if being forced to stand up for herself has made her, ironically, more attractive — an attractiveness we sense from the film's famous finale will never, shall we say, be put to use.

Catherine won't risk allowing her heart to be broken again.

The guy in this video review calls this "new" Catherine "cruel" as if he'd just thought that up, even though she admits to this in the movie's most famous line — "I have been taught by masters" —and he thinks the ending is tragic.

Like this (not incidentally) female critic, I see it as triumphant — is he really ignoring that look of satisfaction on Catherine's face as she ascends that staircase, safely ensconced in a beautiful house that is now rightfully hers, rich without worry, no longer subject to the whims of two nasty men? Frankly, it sounds pretty damned awesome, especially in an era when women's roles were limited.

It may not be everyone's (masculine?) ideal of "freedom," but it's hers.

Conflicting ideas about freedom, coercion, entrapment and the fragility of personality came to the fore in the early 1970s, spurred by the sensational saga of Patty Hearst. Heiress to the (real) San Francisco newspaper fortune that was fictionalized in Citizen Kane, Hearst was an otherwise non-descript college student when she was kidnapped by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a teeny far-left faction so pathetic and bizarre that even the Weathermen considered them a counter-revolutionary embarrassment.

Confined to a closet, repeatedly raped and tortured, Patty notoriously "joined" the SLA, took part in a bank robbery, then a shootout at a sporting good's store, and, when finally freed/captured, declared herself an "urban guerilla."

Paul Schrader's Patty Hearst (1988), as the true story that inspired it, is like the negative of an old "madcap heiress" comedy: The bumbling crimes and cross-country escapades, the "colorful" supporting characters, that somebody ends up in jail (if not for long.)

And there is humor in Schrader's film, which the soixante-huitard audiences in Cannes disapproved of: How dare this movie mock the sacred radical left of the 60s and 70s? Yet the Symbionese Liberation Army were clowns, privileged whites fetishizing their clearly insane Black leader.

Or rattling off incantatory catchphrases with the straightest faces, particularly the SLA's ponderous slogan, "Death to the fascist insect that preys upon the lives of the people."

Watch this video on The Scene.

(One thinks of Leland's drunken scolding of "progressive" tycoon Kane: "You talk about 'the people' as if you own them.")

Schrader didn't write this screenplay, but it feels like he did. His scripts for Taxi Driver (his modern day take on the Western "female captive" mythos-narrative of The Searchers), Raging Bull, Auto Focus and so many other films reveal a man obsessed with the brittleness of the self. Who better to embody that obsession than a woman who remains enigmatic to this day?

Who was the "real" Patty? Was she a victim of brainwashing and Stockholm Syndrome — the bank robbery which gave this phenomenon its name had happened just a year before Hearst's kidnapping — or had a zeitgeist-y revolutionary been "hidden" within the bland heiress all along? After all, she did go to Berkeley...

Catherine Sloper wants to be "kidnapped" by Morris Townsend, her inheritance be damned, and is crushed when he fails to arrive at the appointed hour for their elopement. Did Patty Hearst, somewhere in her soul, wish to be carried off, too? Although I was only ten at the time, I can attest that not a few young women looked upon Hearst, and still do, as a figure of dark fantasy fulfillment. (This is eloquently evoked in a short story by Gen-X author Douglas Coupland.)

Who, we wonder, would willingly exchange wealth and privilege for excitement, high risk, and a kind of romance? And yet, some do.

It's tempting to write that Natasha Richardson's portrayal of Patty Hearst is uncannily perfect — the late British actress' American accent is impeccable — but again, who can say? Schrader's film is stylish, admirably spare — clumsy expository dialogue is kept to a bare minimum — and refuses to glamorize revolution and its crimes, but the final scene hits a false note.

The imprisoned Patty tells her father:

"I finally figured out what my crime was. (...) I lived. Big mistake. Emotionally messy. Pardon my French, dad, but f*** 'em. F*** them all."

It was a crowd pleaser at the time, with one critic writing (and this may sound familiar):

"At the end of the movie, Patty has changed — she's become bitter, manipulative, shrewd — and Schrader suggests that the experience has changed her for the better: The naive little rich girl has turned into a strong, angry woman."

But I sensed something was off while re-watching the film this week, and sure enough, after she'd screened the movie, the real Patty Hearst had only one complaint for Schrader:

"Patty's" dialogue at the end was inaccurate. She'd made no such defiant speech.

Schrader says he replied:

I said, "Patty, I simply cannot make a film where for an hour and a half someone is constantly put upon and never gets a chance to speak their own mind. I know this scene didn't happen, that it's a composite scene. But you were thinking all these things, and you put all these ideas in your book."

But she saw it again and agreed with the scene... because she knew it was true — that people can't watch a movie about a character who does nothing and doesn't finally have a chance to turn to the camera and say, "This is what I think."

Author Christopher Castiglia, who relates this anecdote, dryly notes that, "Schrader's sense that surviving two years of captivity means 'doing nothing' is (...) extraordinary." Indeed, the director seems astonishingly deaf to the possibility that Patty was simply doing to him what she'd apparently done when captive:

Going along to get along.

In The Heiress, we're dropped into a world of rigid manners and mores, of dance cards and calling cards, of bows and "but it's simply not done"s. While set over a century later, in a supposedly more casual, egalitarian era, in Patty Hearst, Roger Ebert argues, we witness a similar mechanism:

During all of the tremendous excitement and passion of her ordeal, [Patty Hearst] hardly seems to be present; this is not a good time for her or a bad time, but a duty. (...)

There is a powerful pressure, felt in all of us, to conform to what those around us consider to be proper behavior. Becoming a revolutionary might have been, for her, a form of good manners.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think of this column by logging into SteynOnline and sharing below. Membership in the Mark Steyn Club has many perks, from commenting privileges, to access to the entire SteynOnline back catalog, to exclusive invitations to Steyn events. Take out a membership for yourself or a loved one here. Kick back with Kathy and your fellow Club members in person aboard one of our annual cruises. We've rescheduled our Mediterranean voyage to next year, but it's sure to be a blast with Tal Bachman, Michele Bachmann and Douglas Murray among Mark's special guests.