Exactly ninety years ago - September 1930 - a new Broadway revue was trying out in Philadelphia: Three's A Crowd - the eponymous trio being Fred Allen, Clifton Webb and Libby Holman. Things were not going well, and indeed were going so badly awry that they might well have deprived us of one of the greatest American pop standards. Everyone had thought the number would be great for Miss Holman. Miss Holman thought differently. Hassard Short, the director, had a very high-concept staging for the song, deriving from an over-literal interpretation of the title. The gimmick he hand in mind would be that you couldn't see Miss Holman's body during the number, just her face, picked out in a spot. So the song would be soulful but disembodied. And they'd put her on a trolley and move her downstage during the number so that the disembodied head would appear to be getting bigger.

Unfortunately, the trolleys made so much noise you couldn't hear the orchestra. And the podium was at such a height that, when Johnny Green stood on it to conduct, his shoulders blocked out Libby Holman's disembodied face.

After a couple of disastrous performances, she yelled, "Instead of calling it Three's A Crowd, call it Two's Company", and walked out.

They talked her back. The high concept was gone. They made sure there were no rumbling trolleys or disembodied heads or other distractions, unless you count the plunging neckline of the slinky black dress they put Miss Holman in. And so, on their very last night in Philadelphia, the song worked for the first time:

Whether Libby Holman ever gave herself to anyone "Body and Soul" I leave to others: She had a penchant for younger men (Montgomery Clift) and older women (Jeanne Eagels), but whether either ever merited the effusions of the above song is doubtful. Nevertheless, on October 15th 1930, opening night at the Selwyn Theatre on Broadway, "'Body And Soul' was a show stopper," wrote Howard Dietz, the show's librettist. It made Libby Holman a star, although not everyone cared for it – "I do not think her big number, 'Body And Soul', is a very good song," sniffed Robert Benchley in The New York Times.

Whether or not it's a very good song, it's a very good tune: The music is rather more popular with instrumentalists than the words are with singers. And it has played a part in many performers' careers: Coleman Hawkins' version is, in Ted Gioa's words, "the most celebrated saxophone solo in the history of jazz", and made the song de rigueur in any working jazzman's repertoire; rather more bleakly, Amy Winehouse's duet with Tony Bennett is the last record she ever made in her short, sad life.

There are four names on the song credits, and who did what can get a little speculative. But the music is indisputably by one man whom I had the pleasure of knowing a little in his final years. Unlike many popular composers, Johnny Green was an accomplished musician - that's to say, a man who could sit down at the piano and (unlike Irving Berlin) play well enough that you'd want to listen to him. He was a terrific conductor and arranger of Fred Astaire's studio recordings in the Thirties, and in the Forties he became Music Director at MGM and was an important part of that big movie sound that distinguished Arthur Freed's musicals of the Golden Age from anybody else's - Easter Parade, An American In Paris, High Society. By this time he was calling himself John Green and writing very few songs, although when he did he insisted that they were way better than the pop stuff he was cranking out in the late Twenties and Thirties. He wrote the title theme for the big Civil War epic Raintree County and once told me with a straight face that it was his greatest ever song, much better than ...well, the number we're celebrating today. I wonder if he ever said as much to Montgomery Clift, the Raintree County star whose lover-mentor introduced "Body and Soul" to America.

Of the trio of wordsmiths attached to the song, the nearest to a solid working lyricist is Edward Heyman, who co-wrote everything from "You Oughta Be in Pictures" and the gorgeous "I Cover the Waterfront" to "Blame It on My Youth" and Nat King Cole's "When I Fall in Love".

But the best known of all Edward Heyman's songs remains his first big hit. "Body and Soul" is one of the most recorded and performed songs of the last century. Aside from Libby Holman, in its first year of life, Ruth Etting, Annette Hanshaw and Helen Morgan all had hits with the song, and in the decades since it's remained the all-time great yearning torch ballad:

My heart is sad and lonely

For you I sigh, for you, dear, only

Why haven't you seen it?

I'm all for you, Body And Soul...

And, without the words, it's everybody's favorite instrumental. You may know Art Tatum's, or Charlie Parker's take, John Coltrane's or Thelonius Monk's, or a thousand other jazz guys riffing on the chords, but it owes its place in the instrumental repertoire to one man alone - Coleman Hawkins in 1939:

Since Hawkins' exuberant meditation put the tune on the map, it would be entirely possible to have a couple of dozen "Body And Soul"s in your record collection and not one with a vocal. In his book Stardust Melodies Will Friedwald calls it "probably the most played melody in all of jazz". Gary Giddins says it's almost impossible to imagine jazz without "Body And Soul". It's certainly up there with "How High The Moon" as one of the most improvised-on chord structures of all time. But the fact remains: it's a song, and with the right singer it can be a very powerful one.

It started like this. It was 1929, and Edward Heyman was writing with Johnny Green and a third man Robert Sour, and dreaming (as he later recalled) that they'd be the most successful triple-threat songwriting team after De Sylva, Brown and Henderson, who gave us "Birth Of The Blues", "It All Depends On You", "You're The Cream In My Coffee", etc. So one day Heyman walks in and says:

What do you think of the title 'Body And Soul'?

Just like that. "Holy Christmas!" said Johnny Green. "That's sensational!" The would-be composer had just quit a clerical job in his uncle's brokerage house. "I was lying in bed one night," Green remembered, "and I suddenly got introduced to myself. 'What are you doing on Wall Street?' I asked. 'You're a musician.' The next day I walked into my uncle's office and told him I wouldn't be back after lunch."

The aspiring triumvirate had had a lucky break. Gertrude Lawrence needed new material and told them to come up with a rhythm song, a comic song, a ballad and a "torch". Heyman was proposing "Body And Soul" for the torch song. The title was suggested to him by a pal. It had been one of those phrases floating around the language for years – "I wasn't earning enough to keep body and soul together" – and one of the quickest ways to a hit title is to take a vernacular expression and make it into a song. Ira Gershwin did it with the popular advertising formulation – "They all laughed when I sat down to play the piano" or whatever. Visiting the Tour d'Argent in Paris, he sent back a postcard: "They all laughed when I said I'd order in French..." Years later, he realized it was more than a postcard joke and wrote "They All Laughed at Christopher Columbus/When he said the world was round..." A cliché isn't a cliché if you turn it into a song. A handful of silent flicks called Body and Soul had already been made, but no-one in Tin Pan Alley had yet spotted the musical possibilities of the phrase.

"Body And Soul" offered something else, too. Will Friedwald finds a pre-echo of it in Uncle Tom's rebuke to Simon Legree:

My body may belong to you, but my soul belongs to God.

In other words, the phrase suggested a black sensibility, too. Even torchier. So, having decided "Body and Soul" was a winning title, all they had to do was figure out what to do with it. Johnny Green once took me through it and made its creation sound as mechanical as a cinematic sex scene recounted by a gynecologist. "First we set the title," he said. "I came up with a triplet phrase leading to a long note on 'soul'. 'Bo-dee-and-soouuullll.' That was our first decision. So then we had to figure out where we were going to put it. Was it going to be at the start of each phrase – 'Body and Soul, I belong to you'? Or should we put it at the end of the phrase – 'I belong to you, Body and Soul'?"

They decided on the latter. "So it was going to be 'blah-blah-blah Body and Soul blah-blah-blah Body and Soul'," said Green, lapsing back into clinical examination, "and then we'd have the release." Ah, yes, that amazing bridge:

I can't believe it

It's hard to conceive it

That you'd turn away romance

No use pretending

It looks like the ending

Unless I can have one more chance to prove, dear...

Wow. That terrific descent through C7, B7, B-flat 7 and back to the main theme. So, I asked Green, where did that incredible middle section come from? And then he explained that he'd taken it out of an earlier song. He'd written a number called "Coquette" for the Lombardo brothers, Guy and Carmen, a couple of years before. Carmen Lombardo liked the main theme but thought the middle was too far out, so he cut it and pasted in one of his own. Green always preferred his original bridge and two years later dusted it off and worked it into "Body and Soul", which presented a whole lot of other problems, one of which he solved by listening to the progressions at the top of the Moonlight Sonata: "If it's good enough for Beethoven, it's good enough for me." And then he hooked it back into the A section with that series of chromatic sevenths. Vernon Duke, the composer of "Taking A Chance On Love", was contemptuous. "You ought to be ashamed of yourself," he told Green. "Anyone can do a descension of chromatic dominant seventh chords." Oh, really? Whether or not that's true, not anyone can descend back to a main theme quite so powerful.

Given the way they approached the component parts like modular furniture, it's amazing the tune flows as effortlessly as it does while having one of the widest ranges of any pop song and undergoing a remarkable series of key changes - in the original, F minor to E flat major to E major to G major and back to F minor – yet all within a conventional 32-bar AABA structure.

The lyric is a slightly different matter. I've never been entirely clear whether they're intentionally evoking the conventions of the my-man-done-me-wrong genre or whether it's just somewhat clumsy:

I spend my days in longing

And wond'ring why it's me you're wronging

I tell you I mean it

I'm all for you, Body And Soul...

"It's me you're wronging"? The final eight bars starts with an even more convoluted word order:

My life a wreck you're making

You know I'm yours for just the taking...

The original text read: "My life a hell you're making" (as Libby Holman sang above). But, in those days, "hell" would have gotten them banned from the American airwaves. So they changed it to "wreck" and got banned anyway: certain radio programmers decided "I'm yours for just the taking" was way too incendiary. As it happens, "hell" may have been a more powerful word but "wreck" sits much better on that note. That hard "k" spits real pain in the middle of the line, whereas the double-"l" would merely have bled into the "you're" and gotten lost.

Gertrude Lawrence liked it, took it back to London, and sang it on the BBC. Britain's top bandleader Ambrose happened to be listening, took a fancy to it, and made it the hit of the town:

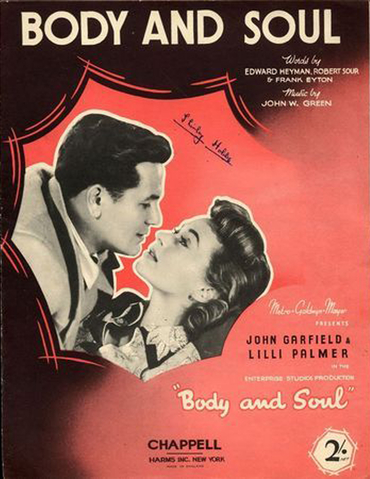

So the all-time great American torch song wound up being published first in Britain, and it was British bandleaders (Jack Hylton) and novelty pianists (Billy Mayerl) and comedienne-chanteuses (Elsie Carlisle) who can lay claim to all the earliest recordings. By this time, a fourth name – the British librettist Frank Eyton – had been added on the credits to the American trio of Green, Heyman and Sour. Whether he actually contributed anything to the composition is unclear, but he certainly helped promote the song in London.

It was that Broadway revue, Three's a Crowd, that brought "Body And Soul" back to America. And, while Robert Benchley may have pronounced it a: not very good song, Paul Whiteman and Helen Morgan begged to differ almost immediately, and across nine decades thousands of other musicians have endorsed their verdict rather than Benchley's. And so it was that an eighty-year-old song became the last recording of Amy Winehouse's short career.

When she recorded "Body and Soul", Miss Winehouse was a few weeks from death, although she surely did not know it. It was for one of Tony Bennett's celebrity-duet albums that he was putting out every other week back then, and they sound for the most part sloughed off in two takes, max. At the age of 112 or whatever, he presumably expected his younger singing partners to work around him and let him take it easy. Amy Winehouse was basically a jazz and standards kid who got detoured into pop stardom with fatal consequences. But she never forgot the music she loved. On the night she won the Grammy, she was dialing in remotely from London, and the nearest thing to non-drug-addled enthusiasm caught by the feed comes when she sees one of the celebrity presenters walk on: "'Ey, dad! It's fooking Tony Bennett!" By the time Bennett walked into Abbey Road for "Body and Soul", her body was on its way out, and he found himself working harder than anticipated in trying to get any soul out of her:

I can't honestly say I'm taken by Tony Bennett's philosophical insights, which is one reason I enjoy Alec Baldwin's dead-on impression of him. But there is a lot of truth in his melancholy observation on Amy Winehouse: Life teaches you how to live it - if you get to live it long enough. Miss Winehouse didn't.

Frank Sinatra and his arranger Axel Stordahl came to "Body and Soul" in 1947 with the help of some memorable solo work from cornettist Bobby Hackett. Sinatra archival expert Charles Granata describes Frank as having "a somewhat introspective approach", and I've occasionally felt - particularly if I've heard this record immediately after bluesier renditions - that it was a bit too dainty. But then I heard Granata's account of what went on in the studio on that November night in 1947. It took both Sinatra and Bobby Hackett a while to settle into the song, to determine what they wanted to say with their respective instruments. Frank's Columbia Records voice is pure and tender, but at this stage it was also beginning to develop darker colors that presage what was to come. On this occasion, he figures out what he wants to do, and dials back the tempo from where Stordahl had originally set it. Not a lot, just a tad.

The first complete take is ravishing: a beautiful orchestral intro, great trumpet work from Hackett, and Sinatra getting the full juice out of every line all the way to a powerful and heartfelt finale. As the last note dies away everybody in the studio is silent, out of respect for the singer and what he has just accomplished. And then from the control booth a booming voice fills the room:

Too long.

That's Morty Palitz, the producer. What he means is, it's three minutes and 23 seconds - which is too long for a 10" 78rpm disc. But, realizing that perhaps he's been a bit brusque considering all the musicians are still swooning, he adds: "Very nice, Frank. But we'll have to speed it up."

Sinatra doesn't want to hear that. "Naw, we can't speed it up," he says. "It'll kill the feeling."

"You'll have to make a cut," suggests Palitz.

Frank is beginning to bristle now. "You mean to tell me a big outfit like Columbia can't put this on a record?"

From the back of the orchestra, a voice pipes up: "We can do it down at Mercury."

Sinatra swings around: "Who said that? Stand up!"

The session oboist rises: Mitch Miller, who when he wasn't playing his instrument had a day job as head of A&R at Mercury, a much smaller record company than Columbia.

"You serious?" asks Sinatra.

"Absolutely!" says Miller. "We could do that at Mercury."

"Take five, everyone," barks Frank - and he, Stordahl, Palitz, engineer Fred Plaut and arranger George Siravo head down the hall to the office of Manie Sachs, a kind of father figure to Sinatra and vice-president at Columbia. It's a one-sided conversation, mostly a blast from Frank: "You mean a big f**king outfit like Columbia can't do what a nickel'n'dime company like Mercury can? I don't believe this sh*t."

But it's true. Nothing can be done. Sinatra heads off back to the studio, and, as his conductor, producer and engineer follow, Manie Sachs, a genteel and polite man not given to such outbursts, hisses at George Siravo: "That f**king Mitch Miller. This guy will never set foot at Columbia Records as long as I'm here!" Instead, of course, within a couple of years Miller was running the joint.

As for "Body And Soul", they went back to the studio, kept Frank's tempo, cut the orchestral intro, came in on Bobby Hackett's trumpet - and managed to fit it on a ten-inch 78. But I prefer it at its original "too long" length:

Almost four decades later, recording LA Is My Lady with Quincy Jones in 1984, Frank put "Body And Soul" on the shortlist before, eventually, setting the song to one side. "I did it for Columbia," he said, "and I can't bring anything new to it."

"But we have much better microphones now," said Quincy Jones.

The answer was still no. He did, however, lay down a vocal, and in 2007, nine years after the singer's death, the Sinatra organization commissioned Torrie Zito to build an arrangement around Frank's voice track. Frank Jr conducted the resulting chart:

No one would account that a primo Sinatra track, and you can see why he felt it wouldn't fit on the loose, jazzy LA Is My Lady. Nevertheless, it gives lyricist Edward Heyman a particular distinction: One month after Frank began his career as a professional singer - July 24th 1939 - on a live radio broadcast from the Marine Ballroom in Atlantic City, the Harry James Band played Heyman's "My Love For You", with vocal refrain by boy singer Frank Sinatra. That makes Edward Heyman the songwriter who stuck with Sinatra the longest - from the James band in 1939 to a technologically created posthumous novelty on a hit album 68 years later: Body and soul.

~If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Ted Nugent, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Paul Simon, Lulu, Tim Rice and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.

Our Netflix-style tile-format archives for Tales for Our Time and Steyn's Sunday Poems have proved so popular with listeners and viewers that we've done the same for our musical features merely to provide some mellifluous diversions in this age of lockdown and looting. Just click here, and you'll find easy-to-access live performances by everyone from Liza Minnelli to Loudon Wainwright III; Mark's interviews with Chuck Berry, Leonard Bernstein and Bananarama (just to riffle through the Bs); and audio documentaries on P G Wodehouse's lyrics, John Barry's Bond themes, sunshine songs from the Sunshine State, and much more. We'll be adding to the archive in the months ahead, but, even as it is, we hope you'll find the new SteynOnline music home page a welcome respite from house arrest without end and revolution on the streets.