Back in the previous century, when I was the youngest employee at a small newspaper, the topic of horror movies came up in the lunchroom.

The twice-my-age-and-then-some ladies seated around me were tutting about one particularly nasty one — or so they'd heard — which had just been released. Movies like that, they all agreed, surely inspired some viewers to commit actual crimes, or at the very least, desensitized others to such real life violence.

I can take or leave most horror movies, but I couldn't help myself.

Pointing to the paperback murder mystery one of my colleagues had in her lap, I asked:

"So how many people get killed in that book you're reading?"

The question of whether or not murder is an acceptable subject for entertainment is hardly new. Thomas DeQuincy wrote his satirical "On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts" in 1827, although Orwell's "Decline of the English Murder", penned in 1946, has proven more enduring. To their credit, many women who are addicted to "true crime" shows and podcasts — and fans are mostly women; HLN isn't nicknamed "the Hysterical Ladies' Network" for nothing — are also willing to ask themselves why.

One true crime case that captured imaginations generations before Ted Bundy and the Zodiac Killer were born was that of Henri Landru. This French serial killer, who was executed in 1922, was nicknamed "the Bluebeard of Gambais" after murdering at least ten women.

I can't make out what made Landru so fascinating in his day (and beyond), but who am I to argue with Proust, Lovecraft (or Rod Serling)?

Or Orson Welles and Charlie Chaplin?

The details were contested by both men, but in short: Welles approached Chaplin in the 1940s, proposing that he star in a film about Landru. Chaplin hated being directed by anyone but himself, so he purchased the rights from Welles and gave him a "story by" credit on the film that came to be called Monsieur Verdoux (1947.)

During his career in silent films, Chaplin was the highest paid actor, and arguably the most recognizable man, on the planet. Unlike many silent stars, Chaplin had nothing to fear from the coming of sound; along with his other considerable talents, he had a beautiful speaking voice.

The trouble was: He used it.

Sound pictures provided Chaplin with an irresistible opportunity to hector audiences with his dangerously naïve political convictions, which he propounded with the all-too-familiar passion of a man convinced such notions had never been expressed before.

According to Buster Keaton, Chaplin once excitedly told him that, "Communism was going to change everything, abolish poverty." Banging on the table, Chaplin continued, "What I want is that every child should have enough to eat, shoes on his feet and a roof over his head." Keaton replied, presumably with his patented deadpan, "But Charlie, do you know anyone who doesn't want that?"

The most infamous example of Chaplin's onscreen pontification is his closing speech in his first talkie, The Great Dictator (1940.)

The sheer, sinister stupidity of this address — with its Shavian, do-gooder nihilism — was summed up superbly by Ron Rosenbaum, author of Explaining Hitler:

"Chaplin, to his eternal shame, ended the film not with a call to oppose fascism, and its murderous hatred, but rather — because he was following the shameful Hitler-friendly Soviet line at the time — ended his film with a call for all workers in the world to lay down their arms — in other words to refuse to join the fight against fascism and Hitler."

Should any additional evidence be required to prove that (contrary to widespread belief) satire is useless, note that Hitler liked The Great Dictator so much he watched it twice.

Chaplin retained his trademark moustache (for obvious reasons) in that film, as well as other trappings of his beloved and highly lucrative "Little Tramp" character. With Monsieur Verdoux, he finally felt confident (or arrogant) enough to dispense with them altogether.

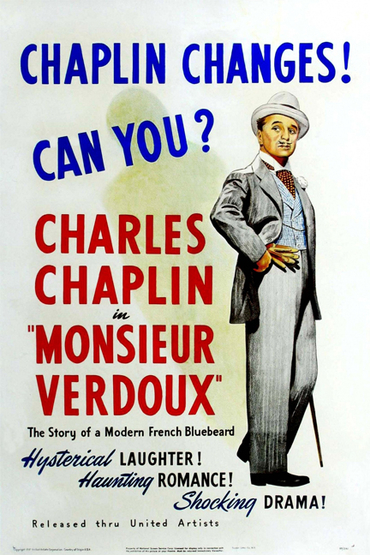

Now, no one can blame any artist for so tiring of their most famous creation that they nuke it to smithereens, but the studio wisely realized that Chaplin's metamorphosis might come as a (financially disastrous) shock; posters for the film asked (or rather, goaded) potential customers: "Chaplin Changes! Can You?"

The answer turned out to be no.

The titular Monsieur Verdoux is a serial bigamist who woos, weds and wipes out lonely, late-middle-aged (and well-to-do) females. His rationale? He was laid off from his job at the bank after 30 years of loyal service, and had to do something to support his saintly invalid wife and their little son.

So far, so whatever. Arsenic and Old Lace had recently completed a three and a half year Broadway run, with Frank Capra's film adaptation opening to great success in 1944; in 1950, a bowdlerized version of Kind Hearts and Coronets received a warm US welcome. Yet staunch (and frequently French) admirers of Monsieur Verdoux would have us believe that American audiences were suddenly (and briefly) repelled by murderous black comedy in 1947.

"Comedy," not "black," is the key word. Monsieur Verdoux isn't funny, and only the most obtuse champion of Chaplin argues that it "isn't supposed to be," that he was "trying to move beyond that." The film is thoroughly punctuated with (awkward) pratfalls and (broad) jokes. They just aren't any good. Anyone unfamiliar with Chaplin's brilliant silents could be forgiven for presuming that Monsieur Verdoux had been made by a different man altogether.

The premise of the film demands that we accept Verdoux as an expert seducer, yet his wooing of his potential marks makes Pepé Le Pew look like Rudolph Valentino.

Then, in scenes with women he's succeeded in marrying, Verdoux is a different man: calm, self-assured and sensible. Shouldn't that have been his conman's calling card to begin with?

Further confusion arises when Verdoux is tried for his crimes. From the dock, and in his cell awaiting execution — his whole "wife and child" thing (which never made sense anyhow) now a forgotten footnote — Verdoux blames his crimes on capitalism. And the war. Or something.

He smugly tells a reporter, "One murder makes a villain, millions a hero. Numbers sanctify, my good friend."

Ah, yes: the microwaved Nietzsche of Rope, which came out the following year. Except Rope was better.

Even if Monsieur Verdoux had been more coherent and hilarious, it was doomed upon release because Chaplin's own behavior off-screen had finally caught up with him. His predilection for barely legal girls was now common knowledge, as were his confused, out of date Soviet sympathies. A small but highly vocal contingent of Americans wanted Chaplin deported.

So all along, his kindly, loveable "Little Tramp" character had served to camouflage an altogether nasty man, who Simon Callow concluded, based on Peter Ackroyd's devastating biography, "was barely human at all."

As one amateur critic has astutely noted, "all of Chaplin's features are about 'saving' someone," yet for all his ranting about "the poor," off-screen he never parted with a smidgen of his staggering wealth to help them.

Does Monsieur Verdoux have any redeeming qualities? Well, there's Martha Raye's (yes, that Martha Raye) indelible performance as one of Verdoux's wives.

And if the film had never been made, we'd be deprived of Alan Vanneman's instant-classic essay about it, which is orders of magnitude smarter and funnier than the movie, and bitchily perceptive:

"We then cut to the home of the Couvais family, wine merchants in the north of France, supposedly – Eula Morgan, Almira Sessions, Virginia Brissac, Edwin Mills, and Irving Bacon – bit players whose braying, mismatched, provincial accents instantly convince us that they are 1) not French, 2) not related, and 3) not actors."

I'll cop out here by handing the last word to Roger Lewis, who was as staggered by Ackroyd's book about Chaplin as Simon Callow was, and tossed in an anecdote of his own:

"Chaplin died on Christmas Day 1977. Ackroyd doesn't mention this, but the comedian's coffin was stolen by grave robbers, who phoned Paulette Goddard, one of his wives and the co-star of The Gold Rush, hoping they could make a ransom demand. 'We've got Chaplin,' they announced. 'So what?' she said, slamming down the phone."

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think of this column by logging into SteynOnline and sharing below. Membership in the Mark Steyn Club has many perks, from commenting privileges, to access to the entire SteynOnline back catalog, to exclusive invitations to Steyn events. Take out a membership for yourself or a loved one here. Kick back with Kathy and your fellow Club members in person aboard one of our annual cruises. We've rescheduled our Mediterranean voyage to next year, but it's sure to be a blast with Douglas Murray, John O'Sullivan and Michele Bachmann among Mark's special guests.