Thanks to the WuFlu, these are sad times for almost all cities across the western world. But in America the lockdown is exacerbated by looting and lawlessness. This last week has seen mayhem in Chicago. Yes, yes, I know that's every week. But this time it reached the hitherto insulated parts of the city, including the "Magnificent Mile", the most expensive retail strip between America's coasts. The March of the Morons may yet shut down the city that Billy Sunday couldn't. So, in an elegaic mood, I offer my favorite Chicago song. In better times, I'd sit on this until its centennial in 2022, but in two years' time I expect it to be full Mad Max on North Michigan Avenue. Whatever Chicago is right now, "toddlin'" doesn't seem to cover it:

Chicago

Chicago

That toddlin' town (toddlin' town)

Chicago

Chicago

I'll show you aroun' (I love it)...

Here's the guy who kept the above song in business for the second half of the twentieth century. Frank Sinatra had a soft spot for "old-fashioned" songs, from his childhood or even earlier: exotica like "The Road To Mandalay" and "Moonlight On The Ganges"; somewhat overwrought plaints such as "The Curse Of An Aching Heart". Usually they'd wind up in the hands of Billy May and were transformed into freewheeling Sinatra swingers that just happened to have faintly wacky lyrics. But this song is different. It was a song from the Roaring Twenties - written when young Frank was six years old - and there isn't really any other way to do it except in Twenties style:

By the way, what is a "toddlin' town"?

A town of uncertain gait, like a toddler's? A town for strolling, sauntering, as in "toddling down to the Drake" or the Wrigley Building? A young town, of toddler-like age compared to the medieval cities its immigrant author knew in his native land?

Or is it the town where they dance the Toddle? The Toddle was one of a zillion American dance crazes of a century ago, but Chicago sure did like it. Headline from The Chicago Tribune, April 21st 1921:

$250,000 Toddle Palace Planned for Woodlawn

Why, only a month before, Chicago witnessed toddlin' nuptials:

Marie Hollernan and George Offerman, both of Chicago, will have a 'toddle wedding' March 2, and, according to Offerman, even the officiating pastor will toddle. A jazz band has been employed to aid in the toddling.

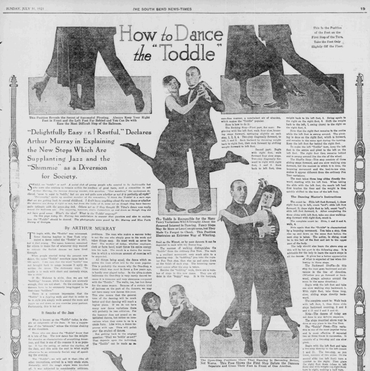

Is the Toddle a real dance - or just one of those alleged dance "crazes" that's a mere pretext for a hit record? Well, Arthur Murray taught it:

The walk is a resilient movement, very much akin to a bouncing step. In 'toddling,' you take the regular Fox Trot step, then rise up and come down at the finish of each step. The bouncing movement comes after the step is taken...

The old rule of 'keep your feet on the floor' is now passé. In the Toddle the girl is permitted to raise her foot high off the floor if she can do it gracefully. This pose shows the position of the feet in the rocking step.

Okay, here's Chicago's Benson Orchestra, arranged and conducted by Roy Bargy. Gracefully raise your foot and go for it:

Today's Chicagoans may prefer lootin' the loot, but just under a century ago they preferred toddlin' the town. Which is why, when one of its most astute songwriters decided to write a ditty for the city, it was inevitable that toddlin' would figure prominently. Amazingly, it was not until 1922 that anyone wrote a song about the Windy City that stuck. "Chicago" captures the spirit of that toddlin' town in the Jazz Age, and has outlasted it by nine decades - and the very transient Toddle craze by almost a century. It's a great explosive musical jolt with a lyric written in pure American. Which is all the more impressive when you consider its author spent the first quarter-century of his life in Germany.

Fred Fisher was born in 1875 in Cologne - the name was "Alfred Breitenbach" back then - and at the age of 13 ran away to sea. He served with the Kaiser's navy, including a stint on an experimental U-boat, and also passed through the French Foreign Legion before washing up in America on a cattle ship in 1900. He Americanized his name to "Fred Fischer", before further refining it to "Fred Fisher", and started composing in 1904. The following year he founded his own publishing house in expectation of massive hits. The first one came a few months later: "If The Man In The Moon Were A Coon". Back then, the two hottest genres in Tin Pan Alley were moon songs and "coon songs" (ie, "All Coons Look Alike To Me", "Coon! Coon! Coon!", "Every Race Has A Flag But The Coon", etc). But, while cynics were already complaining about moon/June clichés, not until Fred Fischer (as he still was) showed up had anyone thought of combining moon songs and coon songs into one boffo category-smashing blockbuster. He sold three million copies. My old sheet music bills it as "A Combination of Classical Music and Comical Words", which is a bit of a stretch on both counts:

If The Man In The Moon

Were A Coon Coon Coon

What would you do?

He would fade with his shade

The silv'ry moon moon moon

Away from you

No roaming round the park at night

No spooning in the bright moonlight

If The Man In The Moon Were A Coon Coon Coon...

And sure enough in the top right-hand corner is a moon bearing a stereotypically smiling Negro face, while down on earth the back yard is plunged into inky blackness enabling nefarious types to break into the chicken coop. "If The Man In The Moon Were A Coon" is of strictly sociological interest these days, and, in the event Chicago has any statues to Fred Fisher, pretext for toppling and tossing in the river, followed by cancelation of his entire catalogue. But, even making allowances for racial stereotypes and all the rest, it's hard to believe, with its plodding tune and one-joke lyric, that it could ever have been popular enough to sell a bazillion copies of sheet music even back in 1905. On the other hand, it's pretty darn assimilated for a guy from Cologne who'd only got off the boat five years earlier.

For the rest of his life, Fred Fisher retained enough of a Teutonic accent that, as his daughter Doris once told me, he pronounced "love" to rhyme not with "stars above" and "turtle dove" but "enough". Yet he certainly understood his market. You're surprised that, having scored big with one ethnic novelty song, he didn't follow it with "If The Man In The Sun Were A Hun". Instead, over the next three and a half decades, he prospered in just about every genre: Irish songs ("Peg O' My Heart", one of the most beguiling of Tin Pan Alley's shamrock ballads), Irish mother songs ("Ireland Must Be Heaven For My Mother Came From There"), substitute mother songs ("Daddy, You've Been A Mother To Me"), technological cutting-edge love ballads ("Come, Josephine, In My Flying Machine"), anti-German love ballads ("Lorraine, My Beautiful Alsace Lorraine"), pro-American love songs ("Would You Rather Be A General With An Eagle On Your Arm Or A Private With A Chicken On Your Knee?"), songs about pedal extremities ("Your Feet's Too Big"), songs about railroad excursions through mining country ("Phoebe Snow The Anthracite Mama"), and songs of sound general philosophy ("There's A Little Bit Of Bad In Every Good Little Girl").

His first movie hit was sung by Fanny Brice in the 1930 film My Man: "I'd Rather Be Blue Over You Than Be Happy With Somebody Else". And there were plenty more where that came from: as he assured Irving Thalberg, MGM's head of production, "When you buy me, you're buying Chopin, Liszt and Mozart." This was more or less the line of the biotuner based on the songwriter's life, Oh, You Beautiful Doll (1949), in which Fisher was played by Hollywood's Hungarian-in-residence, S Z Sakall, as a serious composer who cannibalizes his unperformed opera for Tin Pan Alley hits.

Really? If Fisher ever had an unperformed opera, he was shrewd enough to keep it that way. The great thing about "Chicago" is that there's not a whiff of Chopin, Liszt, Mozart or any other Mitteleuropean influence. It's the most unabashedly American of this German immigrant's hits. When he arrived in America in 1900, he drifted to the not-yet-toddlin' town and took music lessons from a black pianist who made his living playing in the city's saloons. Fred learned syncopation at a time when few other Europeans knew what it was and it gave him a head start in the music biz. His best songs are strung around what the musicologist Ken Bloom calls "quirky rhythms", and "Chicago" is a very good example, one that has all the rhythmic energy you'd want in an ode to a city of gangsters and bootleggers and jazz babies. In 1922, it was one of the first to put little lyric asides in the fills at the end of lines:

Chicago

Chicago

That toddlin' town (toddlin' town)

Chicago

Chicago

I'll show you aroun' (I love it)...

And instant rhymes of the immediately preceding syllable:

They do things they don't do on Broadway. Say...

They have the time

The time of their life...

For an immigrant the lyric is virtually a celebration of the American idiom:

Bet your bottom dollar you'll lose your blues

In Chicago

Chicago...

That's going as native as you can get. As for the music, yes, in the first section that post-Toddle pre-Charleston anticipation-of-the-third-beat trick unmistakeably dates it in the early Twenties, but that second phrase - "Bet your bottom dollar" - could have been written at the height of the swing era twenty years later.

Most Tin Pan Alley "place" songs aren't exactly overburdened with local color. No surprise really. When Yip Harburg wrote "April In Paris", all he knew of France was from a travel agent's poster. When George Gershwin and Irving Caesar wrote "Swanee", their idea of the deep south was Lower Manhattan. When Harold Spina and Walter Bullock wrote "I'd Like To See Some Mo' O' Samoa", they hadn't yet seen any of Samoa. But Chicago was Fred Fisher's introduction to America, and when, two decades later, the opportunist Alleyman decided the city deserved its own anthem he took enough care over the lyrical atmospherics to give a real sense of place to "that toddlin' town". For us foreigners, most of what we know about American cities and states comes from songs, and "Chicago" is a better guide than most. For starters, it's...

The town that Billy Sunday couldn't shut down...

That would be Billy Sunday, born in Ames, Iowa in 1862, and during his heyday with the Chicago White Stockings, according to some baseball scholars, the fastest ball player of the 19th century. But by the 20th the only pitchers he was facing were the ones filled with the demon booze on the tables of some low dive. When he saw the error of his ways, he became the world's most famous evangelist and determined that his burg, too, would see the light. Alas, addicted to liquor and sex and crime, Chicago was the town that Billy Sunday couldn't shut down. And that line has given him an immortality the teetotaler couldn't have foreseen - and certainly more immortality than the first musical attempt to cash in on his celebrity, a song from 1918 called "I Love My Billy Sunday, But Oh You Saturday Night":

'Now I can save the girls,' said he

So I said, 'Save a little blonde for me.'

Indeed. That's by George Meyer, Edgar Leslie and Grant Clarke. By the way, do you know where Billy Sunday had his Pauline conversion?

On State Street

That great street

I just wanna say...

It was one night at the corner of State and Madison. Billy and the boys were well loaded when a gospel wagon pulled up and in the midst of his stupor the old ruin of a ball player heard for the first time in years the Methodist hymns his dear old mother had sung back in Ames. He began to weep. "Goodbye, fellers," he told the lads. "We've come to a parting of the ways." And off he went to the Pacific Garden Mission.

State Street is still a great street. I crossed it a couple of times a day when I was in town for the disgraceful show trial of my old boss Conrad Black and I passed many of the same landmarks Fred Fisher and Billy Sunday would have known, including the Palmer House and the Chicago Theatre. The windy city was one swingin' city in those days. How wild a town was it? So wild that the really crazy exotic transgressive thing to do was take a turn around the floor with your spouse:

They have the time

The time of their life

I saw a man

He danced with his wife...

Paul Whiteman and Al Jolson did the song, and the Dorsey brothers and Django Reinhardt and Count Basie and all the jazz guys picked it up, and then Judy Garland and Rosemary Clooney and Ann-Margret, and there was even an improbable pop-punk take by Screeching Weasel a couple decades or so back. But in Chicago itself, back when Fred Fisher's number was brand new, it was Joe E Lewis' theme song. Lewis is remembered as a comic, but in the Twenties he was a singer, too, with a regular gig at the Green Mill on Broadway. The Green Mill was co-owned by Jack "Machine Gun" McGurn, an associate of Al Capone. In 1927 Joe E Lewis refused to renew his contract with the Green Mill. McGurn was not happy. Shortly thereafter, he bearded Lewis in the Commonwealth Hotel. The singer's tongue and throat were cut. Left for dead, he somehow survived, but it took him years to learn to speak again - and he never sang again.

Thirty years later, Art Cohn wrote a biography of Joe E Lewis called The Joker Is Wild. Sinatra read it and optioned it for the movies. He had been a huge fan of the comedian. "I've always thought Lewis was one of only about four or five great artists in this century - one of them was Jolson," said Frank, and apparently meant it: One of the first things he did when he founded Reprise Records was to sign Lewis to the label to do comedy albums. With The Joker Is Wild, he, Art Cohn, Joe E Lewis and the director King Vidor in effect made an independent film and persuaded Paramount to give 'em 400 grand plus 75 per cent of the profits. There were new songs - Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen wrote "All The Way" for the picture - but there was also "Chicago", in a marvelous Nelson Riddle arrangement that evokes the Twenties yet is for the ages.

When he went into the studio on August 13th 1957 to record it as a single, Sinatra, with Joe E Lewis' blessing, claimed the song as his own. The number didn't really stay in Frank's book over the decades, but he loved Chicago and right to the end he could be counted on to dust it off for engagements in that toddlin' town. I saw him there once, and he opened with the number, full of energy and freewheeling playfulness. He closed, of course, with "My Kind Of Town", the song Cahn & Van Heusen wrote for Sinatra to sing on the courtroom steps in Robin And The Seven Hoods, the 1964 Rat Pack caper that transplants Robin Hood and the rest of the Sherwood Forest gang to the windy city in the prohibition era. No slashed throats and cut tongues, just musical-comedy gangsters. Cahn & Van Heusen knew they had to write a valentine to the city, and would have called it "Chicago" - except that Sammy Cahn respected Fred Fisher's old hit too much. "How about," he suggested to Jimmy Van Heusen, "we call it 'My Kind Of Town (Chicago Is)'?"

It's a perfectly fine song, but it doesn't have all that wonderful period detail that "Chicago (That Toddlin' Town)" has. Nevertheless, Sinatra's second Chicago number was a big surefire showstopper on stage, and one consequence of that was that he stopped singing the old "Chicago". But for seven wonderful years in the late Fifties and early Sixties you could pretty much rely on it turning up in his concerts - in London, in Paris, all over the map. And Fred Fisher's Jazz Age vernacular wound up getting augmented by Frank's ring-a-ding-ding Vegas slang. A few years ago my little girl and I were toddlin' down from Quebec to New Hampshire and over the radio we heard Sinatra sing this:

They have the time

The time of their life

I dug a cat

Who swung with his wife...

We had a newborn kitten in the car that we'd just picked up, and my daughter was most confused by Frank's amendment.

On the other hand, the original line - "I saw a man who danced with his wife" - is sufficiently distinctive on its own that, in turning the number into a big showstopper for Judy Garland, Roger Edens built a verse and a big chunk of the second-chorus patter around it:

Fred Fisher never heard the above. In 1942, after three years of cancer and five painful operations, he hanged himself. That week in America, he was on the Hit Parade with "Whispering Grass", written with his daughter Doris. A third of a century later, in 1975, the same song was Number One in Britain. He bequeathed the world not only his own catalogue but an entire family of songwriters. His son Dan wrote "Good Morning, Heartache" for Billie and Ella (and Natalie Cole and Gladys Knight et al); Dan's brother Marvin wrote "When Sunny Gets Blue" for Johnny Mathis and Nat "King" Cole; and their sister Doris wrote "You Always Hurt The One You Love", "Into Each Life Some Rain Must Fall" and many more. When I spoke to her a few years back, she was riding high on the UK charts with some reformed rocker's cover of "That Old Devil Called Love". I asked whether this heralded a return to the good old days, and Miss Fisher snorted. "Ha!" she said. "They always say that, every time there's an exception to the rule. But that's all it is."

Maybe. But her dad's song is on a ton of Sinatra live albums and anthologies, and, while "Machine Gun" McGurk may have silenced Joe E Lewis' singing voice, the man who took up his theme song has kept it in business for another two thirds of a century - on State Street, that great street, and way beyond.

~Mark will be back right here in a couple of hours with the latest episode of our new Tale for Our Time, The Prisoner of Windsor.

Mark's original 1998 obituary of Sinatra, "The Voice", appears in the anthology Mark Steyn From Head To Toe. For the stories behind many classic Sinatra songs, see Mark Steyn's American Songbook. Personally autographed copies of both books are exclusively available from the Steyn store - and, if you're a Mark Steyn Club member, don't forget to enter your promotional code at checkout to receive special member pricing on those titles and over forty other products.

If you enjoy our Sunday Song of the Week, we have a mini-companion, a Song of the Week Extra, on our audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show - and sometimes with special guests from Mark's archive, including Eurovision's Dana, Ted Nugent, Peter Noone & Herman's Hermits, Patsy Gallant, Paul Simon, Lulu, Tim Rice and Randy Bachman.

The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. You can find more details about the Steyn Club here - and don't forget our special Gift Membership.

Our Netflix-style tile-format archives for Tales for Our Time and Steyn's Sunday Poems have proved so popular with listeners and viewers that we've done the same for our musical features merely to provide some mellifluous diversions in this age of lockdown and looting. Just click here, and you'll find easy-to-access live performances by everyone from Liza Minnelli to Loudon Wainwright III; Mark's interviews with Chuck Berry, Leonard Bernstein and Bananarama (just to riffle through the Bs); and audio documentaries on P G Wodehouse's lyrics, John Barry's Bond themes, sunshine songs from the Sunshine State, and much more. We'll be adding to the archive in the months ahead, but, even as it is, we hope you'll find the new SteynOnline music home page a welcome respite from house arrest without end and revolution on the streets.