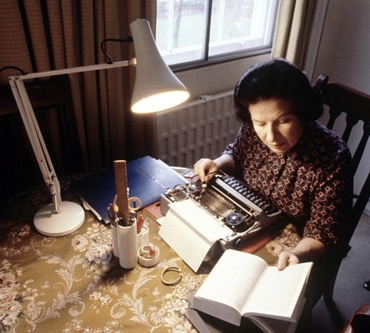

Phyllis Dorothy James was born in Oxford one hundred years ago today - August 3rd 1920. By the time she died in 2014, she was the undisputed successor to Agatha Christie and Dorothy L Sayers as the "Queen of Crime", although she did not care for either comparison ("Such a bad writer," she sniffed of Dame Agatha). In her ninety-four years P D James did a lot of other things, too: She was a Conservative peeress in the House of Lords, and her time in the bureaucracy (she had been a Home Office civil servant) made her an effective chairman of things - whether of the Booker Prize for Fiction, or committees concerned with more earthbound endeavors. I had a slight acquaintance with her during my time at the BBC's "Kaleidoscope", where we used to call her in as a celebrity reviewer. I can recall being slightly skeptical of her judgment only once, when she told me how much she had enjoyed the Bond film The Living Daylights because, unlike Sean Connery and Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton eschewed double entendres and gratuitous sex. Whatever his other gifts, Mr Dalton's earnest approach to the role (including his doe-eyed "sensitive" look with the girls) almost killed the franchise. What appealed to Baroness James about the performance was, in fact, the problem.

When she started out, she figured she'd write a couple of crime thrillers and then move on to "serious" stuff. But Adam Dalgliesh caught on with the reading public, and then with telly viewers, first on ITV and then in America on PBS. So her non-detective novels were few and far between. The enduring one - the one that will ensure her place even if she'd never written a single murder mystery - is her 1992 book, The Children Of Men. It is a profound work, certainly when compared with the non-fiction title that generated all the buzz on the op-ed pages that year, Francis Fukuyama's fatuous thesis on The End of History. While Fukuyama was cooing that the collapse of the Soviet Union marked "the end-point of mankind's ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy as the final form of human government", Lady James discerned, at the very moment of triumph, a fatal enervation in the "free world".

Three decades on, The End of History is too ridiculous to read, while The Children of Men endures as a meditation on the west at sunset. It is a quick read - a short book on a bigger question than anything roiling the news cycle. I've mentioned it a lot over the years, and it turns up toward the end of The [Un]documented Mark Steyn:

To western eyes, contemporary Japan has a kind of earnest childlike wackiness, all karaoke machines and manga cartoons and nuttily sadistic game shows. But, to us demography bores, it's a sad place that seems to be turning into a theme park of P D James' great dystopian novel The Children Of Men. Baroness James' tale is set in Britain in the near future, in a world that is infertile: The last newborn babe emerged from the womb in 1995, and since then nothing. It was an unusual subject for the queen of the police procedural, and, indeed, she is the first baroness to write a book about barrenness. The Hollywood director Alfonso Cuarón took the broad theme and made a rather ordinary little film out of it. But the Japanese seem determined to live up to the book's every telling detail.

In Lady James' speculative fiction, pets are doted on as child-substitutes, and churches hold christening ceremonies for cats. In contemporary Japanese reality, Tokyo has some 40 "cat cafés" where lonely solitary citizens can while away an afternoon by renting a feline to touch and pet for a couple of companiable hours.

In Lady James' speculative fiction, all the unneeded toys are burned, except for the dolls, which childless women seize on as the nearest thing to a baby and wheel through the streets. In contemporary Japanese reality, toy makers, their children's market dwindling, have instead developed dolls for seniors to be the grandchildren they'll never have: You can dress them up, and put them in a baby carriage, and the computer chip in the back has several dozen phrases of the kind a real grandchild might use to enable them to engage in rudimentary social pleasantries.

P D James' most audacious fancy is that in a barren land sex itself becomes a bit of a chore. The authorities frantically sponsor state porn emporia promoting ever more recherché forms of erotic activity in an effort to reverse the populace's flagging sexual desire just in case man's seed should recover its potency. Alas, to no avail. As Lady James writes, "Women complain increasingly of what they describe as painful orgasms: the spasm achieved but not the pleasure. Pages are devoted to this common phenomenon in the women's magazines."

As I said, a bold conceit, at least to those who believe that shorn of all those boring procreation hang-ups we can finally be free to indulge our sexual appetites to the full. But it seems the Japanese have embraced the no-sex-please-we're-dystopian-Brits plot angle, too. In October, Abigail Haworth of The Observer in London filed a story headlined "Why Have Young People in Japan Stopped Having Sex?" Not all young people but a whopping percentage: A survey by the Japan Family Planning Association reported that over a quarter of men aged 16–24 "were not interested in or despised sexual contact." For women, it was 45 per cent.

That's from the "Sex at Sunset" chapter from The [Un]documented Mark Steyn. As I observed, the Japanese are rather more faithful adaptors of The Children Of Men than Alfonso Cuarón, whose 2006 film managed to spend a ton of time and money, hire a fine cast, lavish inordinate care and attention to detail on the film's design and cinematography – and yet completely miss the point of the story in an almost awe-inspiring way: it's virtually a masterclass in mangled adaptation in that the particular and revealing way in which the director misses the point only underlines the thesis of the book.

P D James' original novel is set in the near future – very near in fact, next year: 2021 – in a world that is impotent, literally: The human race can no longer breed. The last children, the "Omega" generation born in 1995, are now adult. Schoolhouses are abandoned and villages are dying as an ever more elderly citizenry prefers for security reasons to cluster in urban centers. As the narrator writes:

The children's playgrounds in our parks have been dismantled. For the first twelve years after Omega the swings were looped up and secured, the slides and climbing frames left unpainted. Now they have finally gone and the asphalt playgrounds have been grassed over or sown with flowers like small mass graves. The toys have been burnt, except for the dolls, which have become for some half-demented women a substitute for children... The children's books have been systematically removed from our libraries. Only on tapes and records do we now hear the voices of children, only on film or on television programmes do we see the bright, moving images of the young...

I read the novel a year or two after publication, enjoyed it, said so to the author at a telly studio one night, and thought about its eerie vision from time to time. The best dystopian novels hinge not on some technological gimmick but on some characteristic of our time nudged forward just a wee bit. In 2006, I wrote America Alone, a book about the demographic death spiral already underway in western Europe, Russia and Japan, and I quoted P D James' novel therein. Another fourteen years on, her prescience seems even greater: The fertility-rate implosion in the developed world was presented initially as a choice - women going to university, women with rewarding careers, women opting to marry later - but it seems to have become pathological and physiological, from the increasing numbers of young persons with no desire for human intimacy to the western world's collapsed sperm counts (which came up on The Prisoner of Windsor the other night).

All this the film version missed, opting for the same generic bleakness as any other dystopian thriller. Let me give a small example. As I mentioned, in our BBC chit-chats Lady James made clear to me that she didn't care for superfluous sex and violence and swearing. So I think it fair to say she would not enjoy the way Cuarón's film translates her protagonist's restrained Oxford English into standard Hollywoodese: "F--k!" "F--k!" "Jesus Christ!" "F--k!"

F--k f--ketty f--ketty f--king f--k. That's how glamorous leading men like Clive Owen are expected to speak, but it's not how his character, a middle-aged civil servant, talks, and it's not how P D James writes. There is one lonely F-word outburst in the novel, all the more effective for its isolation.

So the author would not regard the reflexive expletives as an improvement. But more importantly she might wonder about their accuracy. In the book, as noted above, the infertility of man has been followed by a declining interest in penetrative intercourse. Government efforts to rekindle the spark do not work. In such a world, would "f--k" survive as an epithet?

As for "Jesus Christ!", that too would be less likely to pass their lips – because in a world with no future, whether one regards global infertility as evidence of God's anger or that He is indeed dead or (for a third group in the book) that this is a kind of slo-mo Rapture, very few are as careless about faith as middle-aged Hollywood profaners are. In one of the most striking scenes in the book, a fawn is seen happily loping round the altar in the chapel of Magdalen College in Oxford. It's not quite the same. "Bloody animals," rages the Magdalen chaplain. "They'll have it all soon enough. Why can't they wait?" It is an image of utter civilizational ruin – of faith, knowledge, art and beauty, all lost to the beasts and the jungle:

The choir of eight men and eight women filed in, bringing with them a memory of earlier choirs, boy choristers entering grave-faced with that almost imperceptible childish swagger, crossed arms holding the service sheets to their narrow chests, their smooth faces lit as if with an internal candle, their hair brushed to gleaming caps, their faces preternaturally solemn above the starched collars. Theo banished the image, wondering why it was so persistent when he had never even cared for children.

You can still hear boy choristers in the chapel: they play them on tape. You can still see christenings in churches – for newborn kittens.

Lady James' dictatorship is a subtler one than the film's and most other dystopian visions'. In the book, the "Warden of England" would win any election in a landslide: he knows an aging population wants "security, comfort, pleasure", not untrammeled liberties. One discerns something similar in the west's acceptance of Covid impositions: elderly societies will tend to be risk-averse, even if it means obeying orders to stay inside for six months. P D James' short novel is about loss of societal purpose in society: the symptoms are already well advanced in ours - convenience euthanasia, collapsed birth rates, wild animals reclaiming empty villages on the East German plain, the rejection of the past that necessarily accompanies the abandonment of a future...

All of this is hard for pop culture types like Alfonso Cuarón to grasp. So his third-rate film falls back on hippie anthems, package-tour Eastern spirituality and other cobwebbed cool. The film looks like a film – which is to say that, apart from Michael Caine as some wrinkly old Sixties idealist, everyone in it is young: young transgressive leaders of young gangs pursued by young cops and young soldiers. But that's exactly what the novel has in short supply: paved roads crumble to dirt tracks because the employees of the state are too geriatric and feeble to maintain the rural districts.

What of "youth culture" in a world without youth? I remember the first time I ever visited a Viennese record store - waltzes and operettas as far as the eye can see, with rock'n'pop confined to a couple of bins in the basement. P D James' book is like that: it is a world of the middle-aged and old, a society on its last waltz. Entirely accidentally, the ineptitude of Cuarón's movie makes Lady James' point: A society without youth is so alien to all our assumptions about ourselves that we can't even make a film about it.

P D James lived a long life, vigorous to the end. Pushing ninety, she guest-hosted the BBC's "Today" programme and put the Corporation's ghastly chief executive, Mark Thompson (he's now chief exec of The New York Times), through a forensic grilling that ought to be taught in interviewing school. She was a serious thinker, far more so than the woeful and reductive Mr Fukuyama. At the time I thought The Children of Men was just a whimsical conceit. On this her hundredth birthday, I wish P D James were around to tell her how much I admire it, and marvel at her farsightedness.

~It was a busy weekend at SteynOnline, starting with a brand new edition of The Mark Steyn Show with an update on Campaign 2020, the "respectability" of China, roaring roller babes, moats with alligators, the slough of despond, and much more. Kathy Shaidle's Saturday movie date celebrated not a household name but certainly a household face, and Mark's Sunday song selection offered Tal Bachman's live performance of a lovely Canadian ballad that provided America's first Number One hit record. Steyn also hosted another of his weekend summer specials: an anthology of those lost to Covid, from long-serving law lords to Cameroonian saxophonists. Our marquee presentation was our latest Tale for Our Time - Mark's contemporary inversion of The Prisoner of Zenda: You can hear Rudy Elphberg's attempt to penetrate Windsor Castle below stairs here; his unveiling of a hideous new statue in Trafalgar Square here; and a disastrous Euro-summit here. Or, if you've yet to embark on this latest Tale, you can have a good-old binge-listen from Episode One here.

If you were too busy getting your cat baptised this weekend, I hope you'll want to check out one or three of the foregoing as a new week begins.

Tales for Our Time and The Mark Steyn Show is made with the support of members of The Mark Steyn Club. For more on the Steyn Club, see here.