The first time Peter Green died was one night in 1969, in San Francisco. Or possibly New York. Or Los Angeles or Miami or Chicago. Peter could never remember which. He had died a hundred times since, and after a while, all the deaths blurred together.

Behind that first death lay 22 years of life, most of it spent as Peter Greenbaum, an obscure lad from Bethnal Green in the east end of London.

Aside from jellied eels, rhyming slang, and Jack the Ripper's crime spree 80 years earlier, Bethnal Green wasn't known for much. Nothing in particular augured the rise of a Bethnal Green boy to stardom. Yet at the same time, there was always something special about the unusually thoughtful Peter – particularly his guitar playing.

He'd taken up the instrument at age eleven, inspired by the crisp lead playing of Shadows guitarist Hank Marvin. By age fifteen, he was good enough to play around Bethnal Green for a few quid here and there, though mostly for fun.

But by nineteen, he was good enough to warrant an invitation by British blues singer John Mayall to fill in for his vacationing guitarist – an up-and-coming chap by the name of Eric Clapton – for four dates that December of 1965. The gigs went well, Clapton returned a week later, and Green resumed playing local Bethnal Green gigs at pubs, churches, synagogues, and birthday parties.

And that might have been the last we ever heard of Peter Green, except that six months later, John Mayall and the Blues Breakers recorded the most iconic British blues album of all-time. Officially entitled Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton, but popularly known as "The Beano Album", the record vaulted into the UK Top Ten and made the band famous. In particular, Clapton's soulful, melodic playing on the record sounded like nothing else before it, inspiring awe not only among blues fans and music journalists, but among American blues titans like B.B. King and Buddy Guy. Overnight, Clapton became a musical deity.

And then, he quit. The lead guitar vacancy he left in the Blues Breakers was at once the opportunity of a lifetime and a potential career-killer: Measured against the now-deified Clapton, how could anyone avoid looking ridiculous, let alone manage to shine? Any replacement's potential career could be over before it began.

And yet, when Mayall rang up to extend the invitation, the still obscure Peter Green accepted instantly.

Decca Records music producer Mike Vernon later recounted the moment he first heard about the Blues Breakers personnel change:

"As the band walked in the studio I noticed an amplifier which I never saw before, so I said to John Mayall, 'Where's Eric Clapton?'. Mayall answered, 'He's not with us anymore. He left us a few weeks ago.'

"I was in a state of shock, but Mayall said, 'Don't worry, we got someone better.' I said, 'Wait a minute, hang on a second, this is ridiculous. You've got someone better? Than Eric Clapton?'... Then he introduced me to Peter Green."

It's easy to understand Mayall's enthusiasm. Clapton had turned in an instantly iconic performance on the Beano album. But Green, while firmly rooted in the blues, had his own thing going.

For one thing, there was his actual guitar sound. He used the same model guitar as Clapton (a 1959 Gibson Les Paul) and used the same brand of amplifier (Marshall). Using either the neck or bridge pickup alone, it sounded like every other Les Paul out there.

But when Green switched his pickup selector to the middle position, engaging both pickups, his guitar sounded like no other. Rather than the classic fat, creamy tone of a Les Paul, it suddenly sizzled with clarity and bite.

It was only years later that luthier Jol Dantzig, founder of Hamer Guitars, discovered the reason for the unique sound of Green's guitar: a lucky accident at the Gibson factory back in 1959. Some unknown worker had inadvertently installed one of the pickup magnets backwards. The reversed magnetic polarity caused phase cancellation between the two pickups: certain frequencies just vanished. The resulting sound – the frequencies left over – had the attack and chime of a Stratocaster, but with all the sustain (and just a bit of the beef) of a Les Paul. (You can hear what it sounds like here on the song "The Supernatural").

Green's unique guitar sound wasn't the only thing he had going. He tended to shy away from stock blues licks, preferring to construct his own (relentlessly compelling) note sequences instead. He used standard blues pentatonic (five-note) scales, but threw in exotic lines here and there to spice things up. He avoided flash for flash's sake, instead using his solos to serve the song. He used standard expressive techniques like string bending, finger vibrato, pull-offs, and occasional double-stops, but never sounded derivative.

But there was something more. Green played with a layer of emotional and spiritual depth entirely foreign to standard musical vocabularies. Whether this came more from his early Jewish religious experiences, or an unusually sensitive personality, or from an adolescence spent as an outsider in a predominantly Protestant country, or something else, is difficult to say; but it was that layer of depth which, more than anything, led B.B. King to remark once that Peter Green was the only player who'd ever given him "the cold sweats". It was also what led to the image of Green as something of a mystic.

Green recorded a single album with John Mayall and the Blues Breakers. The band recorded A Hard Road in the fall of 1966. Now a star in his own right, Green left the Blues Breakers July of 1967 to form his own band: Fleetwood Mac.

Named after the Blues Breakers' rhythm section (drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie, both of whom wound up in the new band), Fleetwood Mac struck gold right away. Their eponymously-titled debut album spent a year in the UK Top Ten, helping the new band eclipse John Mayall and the Blues Breakers as Britain's top blues band.

Over the next three years, Fleetwood Mac (which included additional guitarists Jeremy Spencer and Danny Kirwan) released three albums and scored a number of hits, including "Oh Well" and "Man of the World". (Another single, "Black Magic Woman", was a disappointment, rising to only #37 on the UK Singles Chart. It was Santana's Latinized cover version a year later which turned the song into a global smash). The band had even started to make inroads in the United States, touring successfully in 1969, and earning an invitation to play at the Playboy Mansion (video of which you can watch here).

That 1969 tour of America could have been, should have been, the springboard to massive commercial success in America for Peter and his band. Instead, the trajectory went sideways when Fleetwood Mac bumped into Bay Area band the Grateful Dead and their LSD guru, Owsley Stanley (memorialized in Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test). It was with the Grateful Dead one night – in some city no one can remember – that Green and other band members first took LSD; and that was the first time a part of Peter Green died forever.

Peter didn't see it that way. He felt the LSD had enlightened him. And so, he took it again, and then, again, and then, again. Mescaline, too. And the more drugs he took, the more he died. The Peter Green hundreds knew and adored around London began morphing into someone else.

Arriving back in England, he withdrew socially. He began hearing voices. He grew paranoid. Troubled by his own growing wealth in light of Christian warnings against the love of money, he took to wearing robes and a crucifix, and giving his money away to charity. He demanded his bandmates join him in giving away their worldly possessions. (They refused). Increasingly unhappy in a world indifferent to the spiritual realm he believed he had accessed through hallucinogenics, Green contemplated leaving Fleetwood Mac for a different kind of life altogether: one enlightened, thoroughly altruistic, and devoted to the divine.

Consumed by despair and guilt, confused by early stage schizophrenia, Green took another trip again one night in early 1970. In the hallucination that followed, he found himself trying to fight his way back into his own dead body. As he struggled, a green dog – representing the devil that was money – stood before him. He awoke to a dark room, and immediately wrote a song about his vision. It was an eerie, intense, minor key piece, built on pulsing eighth notes. In it, Green fights back against the money he now believed was trying to destroy him spiritually:

Now when the day goes to sleep and the full moon cooks

And the night is so black that the darkness cooks

Don't you come creeping around, making me do things I don't want to do

I can't believe that you need my love so bad

You come sneaking around trying to drive me mad

Busting in on my dreams, making me see things I don't want to seeBecause you're The Green Manalishi with the two prong crown

All my trying is up, all your bringing is down

Just taking my love, then slipping away

Leaving me here, just trying to keep from following you

Released in May 1970, The Green Manalishi (With the Two Prong Crown) would stay in the UK Top Ten for four weeks. It was the last song Peter Green would ever write for Fleetwood Mac.

And it was the last song, because shortly after writing it, Peter, along with bandmate Danny Kirwan, wound up permanently brain-damaged after taking LSD at a party in Germany (which band members discuss here). Neither ever recovered. Green, Kirwan, and Jeremy Spencer would all leave the group for good shortly thereafter. The remaining members would go on to become one of the biggest bands ever, featuring John McVie's wife Christine, singer Stevie Nicks, and guitarist Lindsey Buckingham.

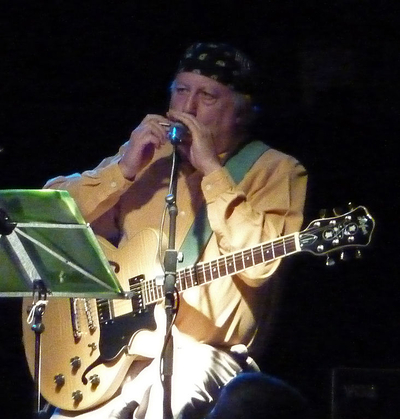

But the larger-than-life Green who, only four years earlier, had out-Claptoned Clapton, spent the next fifty years in an irremediable schizophrenic haze, staying in psychiatric hospitals, relapsing into drug use, undergoing electroshock therapy (dying more and more each time), and working menial jobs like tending cemetery lawns and pushing brooms. Interviews throughout the succeeding decades reveal a child-like man with no idea anything had ever gone wrong with him. Occasionally he got onstage to play again, but... it was just never the same.

The hard, sad truth is that the original Peter Green – one of the brightest musical lights of the 1960s, who should have touched millions for the next five decades with his unique gifts – had already died one too many deaths by 1970, long before he died another hundred deaths prior to his final death this past Saturday, July 25, at the age of 73, on Canvey Island, in Essex.

And that, my friends, is what you call a tragedy. Yes, I'm upset about it. As for what exactly to do about the persistent scourge of drugs in the West, I do have a few ideas...but that's a discussion for another day.

For now, I bite my tongue, and try to feel gratitude for the great songs and guitar performances Peter Green left the world – not disappointment for all the great songs and guitar performances we never got to hear.

May Peter rest in peace, and peace be upon his bereaved family members.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Tal know what they think in the comments, as commenting privileges are among the many perks that come with membership. If you want to join in on the discussion, sign up here. Tal was a great special guest on our first two Mark Steyn Cruises and is set to sail with us again next year, joining Michele Bachmann, Douglas Murray, and of course Mark Steyn himself along the Mediterranean with stops in Monaco, France, Italy, Spain and Gibraltar. Book yourself a stateroom here if you'd like to join us.