I don't spend a lot of time at the New York Times (except for the crosswords) but was prompted to visit late last week by David "Iowa Hawk" Burge, who'd tweeted:

It's a tragedy that her important treatise calling for all men to be killed has been overshadowed just because she attempt [sic] to kill a man

That tweet led to the Times which, as part of their "Overlooked No More" series of belated obits for "significant" gays and lesbians of yesteryear, was "remembering" Valerie Solanas:

On June 3, 1968, Valerie Solanas walked into Andy Warhol's studio, the Factory, with a gun and a plan to enact vengeance. What happened next came to define her life and legacy: She fired at Warhol, nearly killing him. The incident reduced her to a tabloid headline, but also drew attention to her writing, which is still read in some women's and gender studies courses today.

Solanas was a radical feminist (though she would say she loathed most feminists), a pioneering queer theorist (at least according to some) and the author of "SCUM [Society for Cutting Up Men] Manifesto," in which she argued for the wholesale extermination of men.

(Notably, many NYT commenters expressed disgust and dismay at the paper's decision to memorialize Solanas. "Who's next? Charles Manson?" was a common refrain.)

A long-ago roommate of mine had a copy of SCUM Manifesto, and I'm not ashamed to say I own The Female Eunuch, The Feminine Mystique and The Second Sex. Many intellectually inclined women undergo a feminist phase, for the same reason our younger selves devour books about witchcraft:

To try to make sense of feelings of rage (or frustration, or confusion) and possibly discover ways we might channel these inchoate feelings into practical personal power, or something like it.

Fortunately, I later discovered Christina Hoff Sommers, whose Who Stole Feminism? exposed how many "truths" I'd been taught in my single college Women's Studies class were urban legends and shameless propaganda.

But as long as there are angry young women (often with legitimate grievances stemming from trauma and abuse), there will be readers for SCUM Manifesto.

(Solanas herself gave two children up for adoption by age 15, making her a victim of rape, and possibly incest. She was also, not surprisingly, mentally ill, and treatments repeatedly failed; possessed of an IQ in the 98th percentile, Solanas was probably able to "outsmart" many of her doctors, and resented any attempts to "fix" her.)

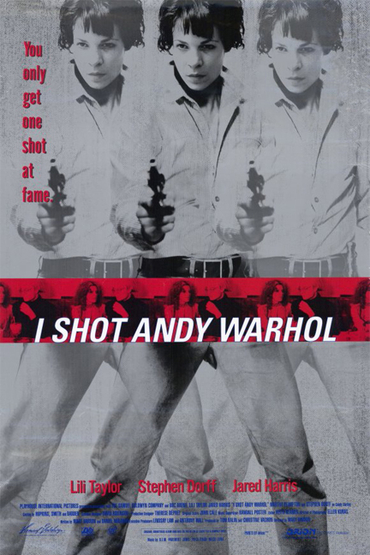

Among those who remain mesmerized by her to this day is filmmaker Mary Harron (American Psycho), who wrote and directed the 1996 Valerie Solanas biopic, I Shot Andy Warhol.

That this was Harron's first feature film makes it particularly impressive. Through kinetic editing and economical yet convincing design, one is completely immersed in New York City street life circa the late 1960s, and in the shabby pseudo-glamor of Andy Warhol's Factory studio and its bizarre denizens — as Roger Ebert noted in his review.

Jared Harris is a stunningly convincing Warhol, but a movie like this one lives or dies on the performance of the actress playing Valerie Solanas, and Lili Taylor should have received an Oscar nomination for her work here.

And that's the problem.

Taylor's Solanas is that rare thing in cinema (and, possibly, in life): A homely, mannish woman who is also charismatic, sympathetic and strangely seductive.

How much she resembles the real Valerie Solanas is hard to say, given how little footage survives of the woman herself. But what matters is that, for most people who see this film, Taylor's Solanas is Valerie; if they happen to be driven to pick up SCUM Manifesto, it is likely they will hear and picture Taylor while they read it, and its message will be far more palatable.

(I expect the opposite has been the case for viewers of the recent American Horror Story episodes that re-enact Solanas' crime — as played by a self-conscious looking Lena Dunham, Solanas is aggressively unappealing.)

As it is, Solanas' text is rife with humor and style, and is compulsively readable in its own weird way. It's difficult to know whether or not Solanas meant it to be taken as provocative, polemical satire in the vein of "A Modest Proposal" — until, well, you know, she tried to kill three men.

(Solanas's gun jammed before she could shoot Warhol's manager Fred Hughes, but art critic Mario Amaya was wounded along with Warhol, who never quite recovered. Having developed a fear of hospitals after the shooting, he delayed medical treatment that might have postponed his death in 1987, at only 59. The general consensus among his friends like Lou Reed is aptly summarized by this headline: "Andy Warhol Was Shot By Valerie Solanas. It Killed Him 19 Years Later.")

Burge followed up his initial tweet with this one.

By and large, anyone who publishes a "manifesto" should be hospitalized for psychiatric evaluation

I'm in general agreement, because with very few exceptions, most "manifestos" are a contradiction in terms.

By definition, they are written to arouse outrage and action amongst the general population, but are more frequently just a record of someone talking to themselves. The Unabomber's manifesto would never have been published if he hadn't killed a bunch of people — and it is, like SCUM Manifesto, still (guardedly) praised as perceptive and prophetic.

Likewise, to the dismay of Betty Friedan, NOW co-founders Ti-Grace Atkinson and Florynce Kennedy lauded Solanas as a heroic role model after the shooting. Ironically, Solanas was never a movement feminist or member of any radical group. While she was initially welcomed by Warhol and his Factory, that supposed haven of freaks and weirdos actually only valued wealthy, beautiful eccentrics. She was soon snubbed as a bore.

Typing alone in her room when she wasn't turning tricks and panhandling, Solanas descended into solipsism. We talk a lot these days about spending too much time inside our own ideological echo chambers, but Solanas heard only one voice: Her own.

Had she pursued, say, stand-up comedy, Solanas might have tempered in a crucible of criticism and feedback, positive and negative.

Sand down her edges and she could easily be mistaken for another misanthropic lesbian who was embraced by Warhol ten years later: Essayist Fran Lebowitz.

Heck, maybe even our Florence — Miss King.

It's fairly easy to imagine both women saying something like Solanas did in a 1977 interview, ten years before her death:

"I consider it immoral that I missed. I should have done target practice."

Regular readers know I'm somewhat obsessed with the notion that "ideas have consequences." We can at least be grateful that Valerie Solanas has merely inspired a good movie, some mediocre art and the name of a music group, rather than murderous copycats who might not have missed.

Although, as 2020 more and more resembles 1968 but with worse music, I'm obliged to add a prophylactic "yet."

As I wrote years ago when considering the toxic legacy of Solanas' contemporary Shulamith Firestone.

Yesterday's mental illness is today's social policy.

Mark Steyn Club members can let Kathy know what they think in the comments. If you want to join in on the fun, make sure to sign up for a membership for you or a loved one.