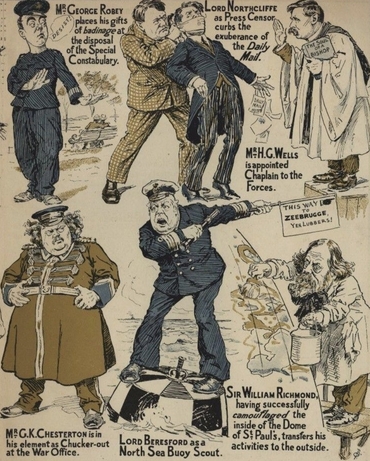

Welcome to the penultimate episode of our current Tale for Our Time - G K Chesterton's metaphysical thriller The Man Who Was Thursday. In tonight's installment our adventure rattles towards its conclusion, with Symes and his weekday colleagues pursuing seeking to put into words the essence of their mortal foe Sunday, even as they pursue him in his balloon:

Syme's eyes were still fixed upon the errant orb, which, reddened in the evening light, looked like some rosier and more innocent world.

"Have you noticed an odd thing," he said, "about all your descriptions? Each man of you finds Sunday quite different, yet each man of you can only find one thing to compare him to—the universe itself. Bull finds him like the earth in spring, Gogol like the sun at noonday. The Secretary is reminded of the shapeless protoplasm, and the Inspector of the carelessness of virgin forests. The Professor says he is like a changing landscape. This is queer, but it is queerer still that I also have had my odd notion about the President, and I also find that I think of Sunday as I think of the whole world."

Members of The Mark Steyn Club can hear me read this penultimate installment of The Man Who Was Thursday simply by clicking here and logging-in. Earlier episodes can be found here.

Nicola Timmerman, a Steyn Club member from eastern Ontario, writes:

This is beginning to remind me of Jules Verne's Around the World in Eighty Days what with balloons, elephants and endless chases.

I wonder how much H G Wells also influenced Chesterton. Apparently Wells and Chesterton were friendly enemies.

In Heretics, Chesterton cites Wells as saying, 'Nothing endures, nothing is precise and certain. There is no abiding thing in what we know.' Chesterton, by contrast, was sure that only those who believed in abiding truth could comprehend true progress. 'If the standard changes, how can there be improvement which implies a standard?' he asks. 'Progress itself cannot progress.'

Wells said that if he made it to heaven, 'it would be by the intervention of Gilbert Chesterton.' And despite Chesterton's criticism of his friend's philosophy, he nonetheless called Wells 'the only one of many brilliant contemporaries who has not stopped growing.'

Wells and Chesterton enjoyed each other's company precisely because they disagreed - on almost everything. In that sense, they belonged to a lost world in which one could take pleasure in grand disputes with a sincere opponent. In our utterly moronized society, that is beyond both the Wokestapo's comprehension and capability: You don't debate the other side; you damn them, ban them, daub RACIST on their front doors, and then burn the joint down.

If you're minded to join our many members around the world in The Mark Steyn Club, you'll find more details here. If you incline more to the Wells end of things than the Chesterton, we have my serializations of both The Time Machine and The Island of Dr Moreau - and don't forget we always do a special live Tale for Our Time on our annual Mark Steyn Cruise, in the event once free peoples are ever again permitted to be out on parole and to venture abroad.

Please join me tomorrow evening for the conclusion of The Man Who Was Thursday - and a few hours before that for the latest audio edition of The Mark Steyn Show.