I know I should be grateful I still have a job — in fact, I'm busier than ever — but I remain envious of those who've been able to curate personal, in-house film festivals during quarantine.

I somehow carved out a sliver of time to browse the Criterion Channel menu last weekend, and as usual, I was overwhelmed.

Yes, I should make myself finally watch, say, Last Year at Marienbad, but as so often happens during these rare intervals, I'm still too wound up from work and other responsibilities (which I could be called away to take up again at any moment) to commit two or three hours to a "deep" foreign arthouse classic.

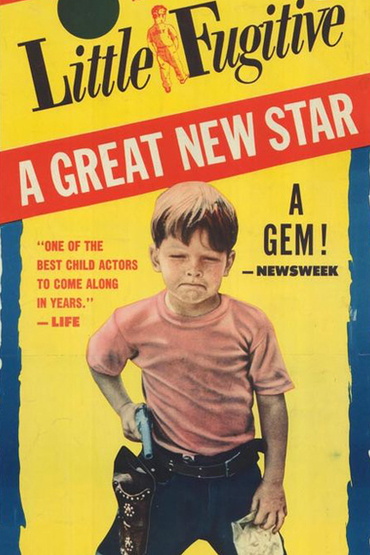

Last weekend was no exception. I clicked on Criterion's "Newly Added" menu and spotted something that looked light and accessible: a 1953 American indie flick called Little Fugitive. So I watched the trailer, and was hooked.

Probably inspired by Rick Polito's famously skewed synopsis of The Wizard of Oz, a jester at Letterboxd.com summed up Little Fugitive this way:

"A young boy celebrates the murder of his older brother by riding all the rides at Coney Island."

And honestly, when I was trying to describe this movie to others after I watched it, I kept typing, then deleting, the word "wholesome," because on the face of it, Little Fugitive doesn't seem to warrant that adjective.

The movie is about a seven-year-old boy named Joey, who yearns to play in the dirty streets and alleyways of Brooklyn with his 12-year-old brother Lennie and his friends, but is constantly rebuffed. When their hard working, widowed mother is called out of town to nurse grandma, Lennie is stuck looking after Joey at home for the next 24 hours, instead of taking his promised birthday trip to Coney Island.

Resentful Lennie and his pals casually plot to kill pesky Joey, but then come up with a less drastic plan to get rid of him, if only for a while:

Using one boy's father's bolt action rifle (and a bottle of ketchup), they trick Joey into believing he's shot his brother dead. "You'd better go on the lam," the "surviving" kids urge him, so heartbroken Joey sets off for... Coney Island. And the adventure of his life.

Guns (real and toy ones); leaving your kids unsupervised overnight, let alone allowing them roam the streets all day — call Child Services!; fistfights and roughhousing; and most of all, a little boy riding the subway alone, then hanging out with strangers at an amusement park — what if they're child molesters?

No, "wholesome" seems wrong, suggesting a cloying, Disney-fied cuteness (likely in a picturesque natural setting) and some kind of After School Special "message." Yet Little Fugitive still deserves that label, more so than the many other child-focused movies that get stuck with it.

And it's not just because the movie was made, and is set in, the 1950s. It would be dangerously naïve to suggest that children growing up in "the old days" didn't risk physical injury, abuse, or abduction and murder. (Google "Albert Fish," "Peter Woodcock" or "The Boy in the Box" at your own risk.) And then there was the polio epidemic, which reached its peak the year before Little Fugitive was shot; children at the time were "warned not to jump into puddles or share a friend's ice cream cone."

So we can argue whether or not, with all its neo-realistic, cinéma vérité grittiness, Little Fugitive is an entirely accurate depiction of its place and time, one we should wholly aspire to return to, where children could run free and fearless, unconstricted by our era's regimented playdates, hyper-organized competitive sports, bicycle helmets, toddler beauty pageants and fad-chasing, helicopter parents.

Then again, perhaps it demonstrates how low we've fallen when we see horse-obsessed Joey being befriended by the fellow who works at the pony rides, and panic:

Yeah, no. Like the other adults Joey encounters in his little odyssey, this one is simply a kindly, patient man, and while it isn't foregrounded, knowing that the boy's father is dead gives Joey's "crush" particular poignancy.

Is that sentimental and unrealistic — or are we just cynical and jaded?

Alas, by today's "standards," Little Fugitive isn't "dark" and "realistic" enough apparently. One Joanna Lipper remade the movie a dozen years ago. Lipper "has PhD in Women's Studies via the Creative Practice of Documentary Film. As a Lecturer at Harvard University, she taught Using Film For Social Change."

Her unasked for (and largely unseen) remake "explores the themes of child neglect, the challenges and heartbreak of children of incarcerated parents, the inadequacies of the foster care system, and sexual predators."

I haven't seen it and don't intend to.

The original movie was made by married street photographers Morris Engel and Ruth Orkin, on a budget of only $30,000. (Disappointingly, of all the essays I subsequently read about this movie, only one bothered to mention that Orkin also took one of the most recognizable and reproduced photographs of the mid-20th century, "An American Girl in Italy." To the relief, or disappointment, of millions of female admirers, the seemingly distressed young lady at the center of the picture now insists that the iconic image is a symbol of empowerment rather than victimhood: "I was having the time of my life.")

At a time when most amateur films were shot on 16mm, and long before the Steadicam was invented, Engle had an engineer friend construct a portable 35mm (that is, Hollywood studio quality) camera he could strap to his shoulder and even conceal if necessary. (Stanley Kubrick was so impressed by this device that he asked to borrow it.)

However, this meant Little Fugitive was shot without sound. While the subsequent dialogue dubbing is a little rough at times, remember that (as with another earthy, "boy's life" classic, Pather Panchali) all the actors are amateurs. And the Foley artists who added all the ambient sound post-production did a tremendous job here.

Little Fugitive earned an Oscar nomination for Best Original Story, won the Silver Lion at Cannes, and became one of the touchstones of what would become the nouvelle vague, "if only in the Thor Heyerdahlian sense of proving what was possible with the tools and ambition at hand."

John Cassavetes was so inspired by Engle and Orkin's achievement that he started making low budget movies, too. Francois Truffaut later declared, "Our New Wave would never have come into being, if it hadn't been for the young American, Morris Engel, who showed us the way with his production, Little Fugitive." Truffaut, of course, went on to make his first film, The 400 Blows, which, not incidentally, is about a runaway boy who also, famously, ends up at a beach...

I wish I'd discovered this movie a month ago, before the lockdown was beginning to lift — cabin-feverish parents and children alike could have left their homes vicariously, thrilling (or squirming) at Joey's perilous yet joy-filled journey through a (now lost forever) New York City — and his chastened brother's desperate, parallel quest to find the tot before mom gets home.

That said, Little Fugitive is still very much worth watching, any time at all. Besides being available at the Criterion Channel, it can be streamed from SundanceNow.com, and the DVD of the superb Kino Lorber restoration is for sale at Amazon.com. It airs occasionally on TCM, but alas, no broadcasts are scheduled for the near future. Please don't watch the poor quality prints on YouTube — it really needs to be seen in its original black and white glory:

Let Kathy know what think of this review in the comments. If you want to join in on the conversation, consider joining the Mark Steyn Club. From access to exclusive Club events to discounts to SteynStore products, to, of course, commenting privileges, there are perks for all in the Mark Steyn Club.